Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (ca 1562–1621) put his stamp on not only the music of the Netherlands but also that of North Germany, as a teacher of those who became the players of the North German School, and on English keyboard music, being one of the few continental composers to appear in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book.

Gerrit Pietersz Sweelink: Portrait of Jan Pietersz. Sweelinck, 1606 (Kunstmuseum Den Haag)

In this new recording by Italian pianist Andrea Vivanet, we are given a broad view of Sweelinck’s output from his toccatas, variation sets, and his fantasias. One of the problems with Sweelinck in modern ears is his long association with the stern and the intellectual. Sweelinck was the first to codify the modern fugue we know so well from Bach: begin with a single melody and expand the voices sequentially. What could so easily become mechanistic becomes, in Vivanet’s hands, living and bright. He brings to the world of Sweelinck a sense of discovery and adventure.

Andrea Vivanet

Sweelinck was the eldest son of Peter Swybbertszoon, who had been appointed organist at the Oude Kerk, Amsterdam’s oldest parish church. At his father’s death in 1573, when Jan was 11, little is known of Jan’s musical education. In 1577, at age 15, Jan took his father’s former position at the Oude Kerk and served there for 44 years. At his death, his son Dirck Janszoon Sweelinck succeeded his father at the organ in the Oude Kerk.

The first publications by Sweelinck (when he took his mother’s family name, as his father did not have one), date from 1592. After his first 3 books of chansons, he compiled four large volumes of psalm settings, published between 1604 and 1621, the last appearing posthumously. Sweelinck seems to have spent his entire life in Amsterdam with only rare trips outside the city, usually for professional reasons such as organ inspections and assessments, advising on organ building and restoration, or buying instruments. Even being only in Amsterdam, his name was internationally known, and he was given the nickname ‘the Orpheus of Amsterdam’ for his skill at the art of improvisation. City authorities frequently showed off his prowess at improvisation to official visitors.

We spoke with Andrea Vivanet recently about playing Sweelinck on the piano and what he discovered. He said that he’d started a few years ago to discover Sweelinck when he was looking for new repertoire. He explored a few pieces and eventually had a body of work that could be recorded. For Vivanet, it was very much a voyage of personal discovery, rather than a set repertoire to perform.

In moving the music to the piano, there were some non-obvious technical elements to consider, such as sound duration. The ability to sustain a sound is very different between a harpsichord, an organ, and a piano, and some pieces that worked well on the organ didn’t work well on the piano. The style of performance was also a question: should the notes be detached or legato? Choral-like or harpsichord-like? One of the advantages of the piano, on the other hand, was its volume of harmonies. Its ability to sustain a rich sound, unlike the harpsichord, and the sounds that the piano pedals made available, made works such as the Echo Fantasias possible.

We also talked about tuning systems. Sweelinck is very much part of the world of modal music, and Vivanet said, much of the music of the late Baroque to now is purely major/minor. After decades of practising the fingering of the familiar scales, he now had to decide what would be the best fingering for a Dorian scale versus an Aeolian scale.

The Echo Fantasias have their own links with other genres, such as fugue, as is evident in the opening of the first Echo Fantasia on the recording. Listen too, for how Vivanet handles the echo phrases.

Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck: Echo fantasia in Dorian mode, SwWV 261 (Andrea Vivanet, piano)

This is the kind of recording that lets you discover a composer that you perhaps knew many years ago but hadn’t explored recently. The liveliness of the performances is matched with an underlying thoughtfulness in assembling the collection that only invites deeper listening.

For his next project, Andrea Vivanet will jump forward in time by nearly 400 years to look at the music of Claude Debussy and Manuel De Falla. The lessons in modal harmony learned from Sweelinck will come into play again as Debussy discovers the joys of the modal world when he ventures out of major and minor to the new discovery of alternative tuning systems that came back in the late 19th century.

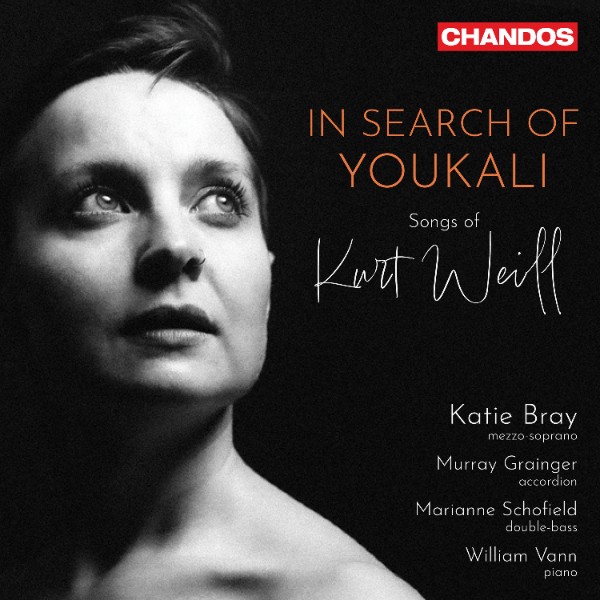

Sweelinck: Keyboard Works

Andrea Vivanet, piano

Piano Classics PCL10280

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter