In the world of music, chords are more than just a collection of notes; they are the colors with which a composer paints emotion. Most people learn early that Major sounds “happy” and Minor sounds “sad.” While this simple heuristic is a useful starting point, it only scratches the surface. The true emotional depth of music emerges when we examine how interval structures and dynamics (volume) interact to shape the listener’s psychological and emotional experience.

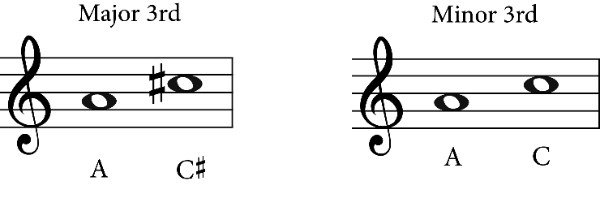

The Building Blocks: Major vs. Minor Thirds

The fundamental difference between a Major and a Minor chord lies in the “third”—the second note of the chord. This small shift of just one semitone changes both the physical vibration and the emotional resonance of the chord.

- The Major Third (4 semitones): Found early in the natural overtone series, this interval feels stable, grounded, and “pure.” It conveys brightness and resolution.

- The Minor Third (3 semitones): Slightly compressed, it introduces acoustic tension. Our ears perceive this as subtle unease, longing, or introspection.

It’s remarkable how a single semitone difference can produce such a wide range of affective responses—a testament to both physics and human perception.

The Influence of Dynamics

© Hoffman Academy

Dynamics—the loudness or softness of music—does more than make a chord louder or softer. They alter the “gestalt” of the sound, shifting its emotional weight. By considering chord type alongside volume, we find four distinct emotional states:

Chord Type | Loud (Forte) | Soft (Piano) |

|---|---|---|

Major | Triumphant – Radiant and victorious, like a celebratory fanfare | Content – Gentle and at peace, like a calm morning or quiet satisfaction |

Minor | Angry/Dramatic – An outcry or rebellion, turbulent and threatening | Melancholic – Intimate and fragile, like a whispered secret or a lonely sigh |

This four-quadrant model illustrates that emotional meaning in music is not inherent to a chord alone—it is co-created by the performer’s choices.

Historical Context: How Composers Used Emotion in Chords

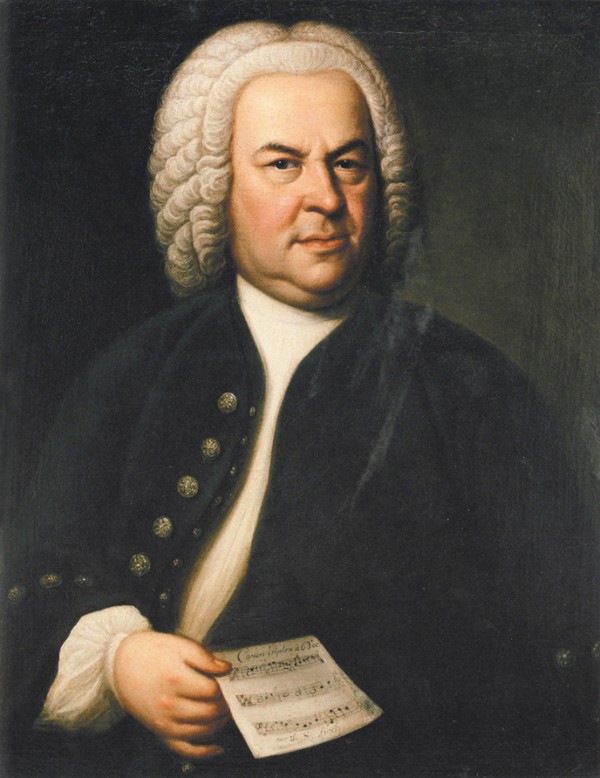

Baroque Clarity

Elias Gottlob Haussmann: J.S. Bach, 1746 (Bach-Archiv Leipzig)

In the Baroque era, composers such as Bach and Handel exploited the contrast between Major and Minor with careful attention to affect. Major chords often punctuated triumphant or spiritual passages, while Minor chords conveyed penance or sorrow. The use of dynamics was subtler than in later periods, relying on melodic emphasis and ornamentation rather than extreme volume shifts.

Classical Precision

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

The Classical period saw composers like Mozart and Haydn refine the emotional palette. Major chords were associated with social celebration, ceremonial contexts, or joyful dialogue. Minor chords, though sparingly used, created dramatic tension, surprise, or introspective moments. Crescendos and decrescendos allowed performers to shape the emotional narrative dynamically.

Romantic Depth

Maria Wodzińska: Frédéric Chopin, 1836 (Wasaw: National Museum)

Romantic composers embraced extremes. Beethoven, Chopin, and Verdi manipulated both chord quality and dynamics to evoke a wide emotional spectrum—from the intimate melancholia of a Chopin nocturne to the thunderous anger of a Verdi Requiem. Minor chords became not just sad, but capable of expressing rage, suspense, or longing; Major chords ranged from triumphant to serene contentment.

Modern Applications: Pop, Jazz, and Film

The emotional power of chords extends far beyond the classical canon. In pop music, Major chords often carry uplifting choruses, while Minor chords set a reflective or moody verse. Jazz musicians exploit chord extensions—such as minor sevenths or augmented sixths—to blur emotional boundaries and create sophisticated tension.

Film scores amplify the connection between dynamics and emotion. Consider the swelling Major chords in triumphant cinematic finales or the soft Minor chords underscoring a character’s vulnerability. The interplay of chord type, dynamics, instrumentation, and rhythm shapes the audience’s visceral response, sometimes without conscious recognition.

Psychoacoustics: Why We Feel What We Hear

Our perception of Major and Minor chords is grounded in both physics and psychology. Major thirds align closely with the harmonic series, which the human ear naturally interprets as consonant and stable. Minor thirds introduce slight deviations that produce acoustic friction, triggering a sense of longing or tension. Dynamics further modulate these effects: louder chords command attention and assert presence, while softer chords invite intimacy and introspection. In essence, the brain interprets the combination of pitch intervals and amplitude as an emotional narrative.

Interactive Exploration: Hear the Four Emotional States

© chopinacademy.com

To gain a primary understanding of these states, musicians and listeners can engage in the following exercise on a piano or keyboard:

Play a Major chord loudly: Feel the Triumphant energy.

- Play the same Major chord softly: Notice the sense of calm and Contentment.

- Play a Minor chord loudly: Hear Anger or Drama emerge.

- Play the Minor chord softly: Sense Melancholy and intimacy.

These simple exercises reveal how subtle shifts in performance transform a single set of notes into a complex emotional language.

Masterpieces in Context

Here are iconic examples that showcase the four emotional states:

- Triumphant (Loud Major): Beethoven, Symphony No. 5, 4th Movement – the full brass fanfare in C Major radiates victory.

- Content (Soft Major): Grieg, Morning Mood (Peer Gynt) – E Major flute melody evokes peaceful satisfaction.

- Angry (Loud Minor): Verdi, Dies Irae (Requiem) – thunderous G Minor chords convey divine wrath.

- Melancholic (Soft Minor): Chopin, Prelude Op. 28, No. 4 – descending E Minor chords express intimate longing.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 67 – IV. Allegro (Zagreb Philharmonic Orchestra; Richard Edlinger, cond.)

Edvard Grieg: Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46 (version for narrators and piano) (narrated in English) – I. Morgenstemning (Morning Mood) (Einar Steen-Nøkleberg, piano)

Giuseppe Verdi: Messa da Requiem: Dies irae (Chicago Symphony Chorus; Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Daniel Barenboim, cond.)

Fryderyk Chopin: 24 Preludes, Op. 28 (excerpts) – No. 4 in E Minor (Sviatoslav Richter, piano)

These examples illustrate how composers across centuries have harnessed chord quality and dynamics to communicate nuanced emotions.

Conclusion

Understanding music requires moving beyond simplistic labels. A Major chord is not merely “happy”—it can convey triumph, serenity, or contentment. A Minor chord can evoke sadness, longing, or even explosive anger. Dynamics, context, and performance breathe life into these mathematical structures, transforming abstract vibrations into vivid emotional landscapes.

Music is, at its core, a dialogue between sound and listener. By recognising the interplay of chord structure and dynamics, we gain deeper insight into the emotional architecture that shapes every composition, from Baroque counterpoint to modern film scores.

Bernd Willimek

Bernd Willimek is a music theorist and researcher focusing on the psychological foundations of musical expression. Together with Daniela Willimek, he co-developed the Theory of Musical Equilibration, which explains emotional responses to music through the listener’s identification with processes of the will. Their work has been published internationally and applied in music theory, psychology, and music education.

Daniela Willimek

Daniela Willimek is a pianist, music educator, and researcher focusing on music psychology and emotional perception in music. She is a lecturer in piano at the University of Music Karlsruhe and has recorded CDs featuring works by female composers. Together with Bernd Willimek, she co-developed the Theory of Musical Equilibration, which explores how musical structures convey emotional meaning in performance, analysis, and pedagogy.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter