Charles Tournemire à Sainte-Clotilde

Collection Odile Weber

(Jean-Marc Leblanc, “Mémoires de Charles Tournemire: Édition critique,”

L’Orgue. 2018 I–IV, nº 321–324, page 276)

To Speak One’s Own Language

The French organist Charles Tournemire (1870–1939) is one of the great enigmas in the musical world. He graced humanity with a formidable œuvre, which includes symphonies, operas, chamber music, and, of course, organ works, yet he has been relegated to the periphery in the musical canon—none more so than his magnum opus, L’Orgue Mystique. This mammoth, two-hundred-fifty-three-movement, fifteen-hour-long liturgical work, based upon over three hundred Gregorian chants, is of Wagnerian scale and is equally enmeshed with and a challenge to the cultural currents of Tournemire’s time as Wagner’s own masterpieces were to his era. While Wagner would garner caché and would be revisited throughout history, L’Orgue Mystique and Charles Tournemire are little known—even among organists—and are seldom experienced. Why should this be so?

Tournemire’s student and his eventual successor to the organ loft of Sainte-Clotilde, Jean Langlais (1907– 1991), offered this sage insight: “This music is very difficult for many people, because Tournemire wrote unlike anyone wrote before him and anyone after him, and that is very dangerous for an artist—to speak his own language.” The term language—in this instance—speaks not simply to musical constructs such as Affeckt, harmony, or structure, but to the greater systems that Tournemire’s language sought to articulate.

Jean Langlais’s reminiscences of his maître Charles Tournemire

Charles Tournemire devant le portail de Sainte-Clotilde

Collection Daniel-Lesur

(Jean-Marc Leblanc, “Mémoires de Charles Tournemire: Édition critique,”

L’Orgue. 2018 I–IV, nº 321–324, page 270)

The Issue of Religion

Undeniably, the subject matter of Tournemire’s works—namely that of religion—both imposes upon Tournemire subjective labels and categorisations that make him problematic. These issues are not simply an emanation of the wrangling between theism and atheism or inter-denominational punctilios; they speak to the true nature and purpose of religion as opposed to its practice.

The existential purpose of religion, which is rooted in ontology and the exploration of the bounds of human epistemology within Divine ineffability, is often overshadowed by more immediately appealing anthropocentric needs or desires, such as personal identity, meaning, and easy cognizability. Religion is a philosophical system of ontology. However, in practice, religion is often institutionally banalised both by well-meaning, intellectually underdeveloped parochial clergy and by hieratical pragmatists fearful of empty pews. Indeed, most of the public finds pondering to be too ponderous, and that the role of religion is that of a Rotary Club—a source of community, meaning, identity, and self-gratifying good deeds—and as a framework to “proof text” and thereby legitimise one’s own significance and personal desires. Religion’s true purpose—a theocentric contemplation of the ontic within the phenomenological and the apotheosis or henosis of the created with its Creator—is lost in the welter of more anthropocentric priorities. These theocentric and anthropocentric realms each have their own function, systems, and, therefore, languages that must be understood independently from one another, even though there are prima facie overlapping facets.

Tournemire’s religion was not that of the pulpit or the pew—an institution fighting for its existence or laity longing for community and a self-affirming identity—but of that of a “mystic”—a theological metaphysician whose language was that of art—or more specifically, music. He insisted upon upholding the highest ideals with regard to the vocation of organist, averring a musical axiology, famously writing that “Organ music where God is absent is a body without a soul.” (136)

How did this come to be?

Richard Spotts: Sunday Afternoon Recital (October 16, 2022)

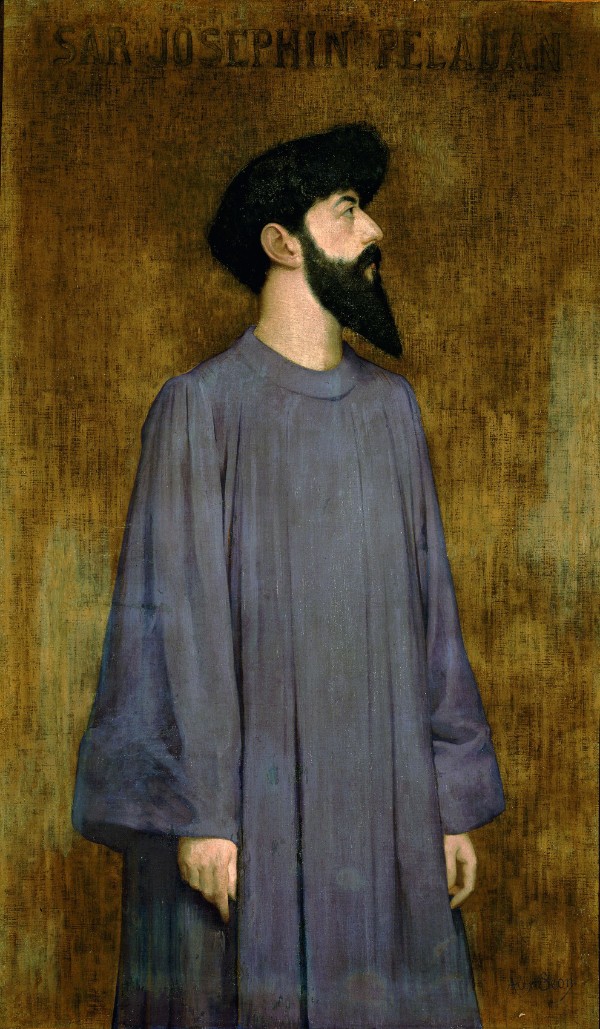

Alexandre Séon

Sâr Péladan, the Symbolists, and Chant

Tournemire’s spiritualformation blossomed after hismarriage to Alice Georgina Taylor(1870–1920) in 1903. Alice Taylor’s sister, Christine [Christiane] Taylor, became the second wife of Joséphin Péladan (1858–1918), a French mystic who was a leading figure of the Rosicrucian or the French occult revival. He was the founder of the Ordre de Rose a Croix in Paris and a leading proponent of the Symbolist Movement.

“Sâr” Péladan, as he would later be known, was a brilliant character—if a bit eccentric. Tournemire recollected: “Péladan had found a way, as only a few men over the centuries, to be able to store within the vast satchel of his memory all of the intellectual production since Antiquity! He had acquired, so to speak, memory without failure, but he sometimes had dubious judgment! Nevertheless, his vast erudition made him a walking and ‘portable’ library.” (121)

Of art, Péladan remarked: “Art is man’s effort to realise the Ideal, to form and represent the supreme Idea, the Idea par excellence, the abstract Idea. Great artists are religious because to materialise the Idea of God, the Idea of an angel, the Idea of the Virgin Mother, requires an incomparable psychic effort and procedure. Making the invisible visible: that is the true purpose of art and its only reason for existence.” (122)

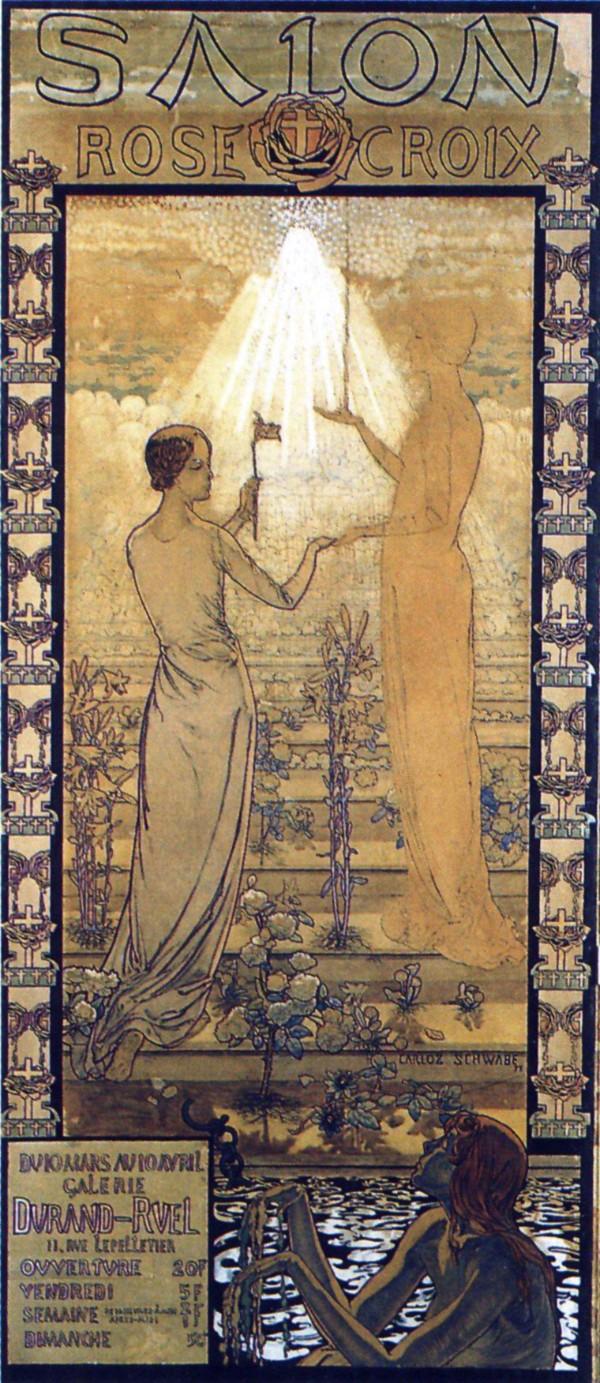

Salon de la Rose+Croix

Between 1892 and 1897, Péladan hosted six Salons de Rose a Croix whose subject matter dealt with religion and mysticism. Involving over two hundred visual, literary, and performance artists, these salons served as a popular promotional vehicle for the artistic endeavours of the Symbolists.

The Symbolist Movement first emerged in the literary genre through the poetry of Charles Pierre Baudelaire (1821–1867), Paul-Marie Verlaine (1844–1896), and Stéphane Mallarmé (1842–1898), as well as the plays of Maurice Polydore Marie Bernard Maeterlinck (1862–1949). However, it expanded into the visual arts and later the performing arts.

The poet Jean Moréas (1856–1910) published what would become known as the Symbolist Manifesto [Le Symbolisme] in Le Figaro on the eighteenth of September 1886, an essay that articulated and officially launched the movement. In the article, Moréas wrote that one should “clothe the Ideal in sensible form.” He continued: “Thus, in this art […] none of the concrete phenomena are manifestations of themselves: these are rather the sense-perceptible appearances whose destiny isto represent their esoteric affinitieswith primordial Ideals.” (122)

Owing much to Schopenhauerianism and his Neo-Platonic vision of the world, the Symbolists—through literature, the visual arts, and music—sought to grapple with the nature of Truth—delving behind the dull, encrusted veneer of phenomena whose patina hides greater things. In the Symbolist world, art sought to exhibit correspondence with the noumenal through the semiotic use of figurative ontic imagery to evoke a sense or ken of the ontological—the invocation of a deeper or, perhaps, latent form of intellectual engagement. In the Symbolist conception, art istheology and philosophy—not simply æsthetics or a sensual delight and amusement. Here, art is a kind of language—a conceptual, communicative medium used in philosophical discourse—and a tool of epistemology. Theirs was a qualitative versus a quantitative linguistic and conceptual system—a system that they felt to be more apposite to the perception and denomination of the ineffable nature of Truth than the comforting realm of Materialist categorisation.

Charles Tournemire: Photo Guy Ringenbach 25 sept 1928

Collection Daniel-Lesur et Societé Baudelaire

(Jean-Marc Leblanc, “Mémoires de Charles Tournemire: Édition critique,”

L’Orgue. 2018 I–IV, nº 321–324, page 271)

Informed by the Symbolist outlook, Tournemire also came to revere the literature of the nineteenth-century novelists, essayists, andCatholic Mystics, Joris-Karl Huysmans(1848–1907), Ernest Hello (1828–1885), and Léon Bloy (1846–1917). Bloy, who has been given the moniker “The Pilgrim of the Absolute”, spoke to the issue of the language of the “mystic”, saying, “I am so much at home in the Absolute that the man who does not speak the language of the Absolute tells me nothing.” (126)

It was also at this time that the monastery of Solesmes promulgated their conception of Gregorian chant, who, through their new semiological and paleological studies, reintroduced melodic and rhythmic conceptions of these ancient melodies that would ultimately inform Tournemire’s own musical output. Indeed, the Liber Usualis would be Tournemire’s vade mecum. Every week, he would set the Liber on the organ and improvise on the prescribed chants for the day. When asked how he saw his role as organist, Tournemire replied:

I see it very tightly fused with the liturgy, that is to say, taking inspiration from the splendour of the liturgical texts and Gregorian lines as “the aerial and mobile paraphrase of the immovable structure of the cathedrals.” [Huysmans] In short, it is advisable to comment every Sunday on the Divine Office by means of improvisations or works directly related to the texts of the day. (375)

Reminiscences of Alice Tournemire née Espir of her husband, Charles Tournemire

L’Orgue Mystique

It was through these germinal influences that L’Orgue Mystique was born. Written between 1927 and 1932, using a liturgical framework, Tournemire created a work that was both an act of devotion and a musical exegesis based upon chant “libretti”. Whereas many composers of lesser merit simply use a chant or chorale as a thematic motive to explore musically, informed by the Symbolists, Tournemire looked to the theology behind the chant and saw chant melody as a vocabulary to express that theology.

When describing L’Orgue Mystique, he frequently used the term paraphrase, which refers not simply to its musical note citation but to its theological hermeneutic. He called the final movement to each Office a résumé, meaning a compilation of thoughts for each feast. Hence, it is not just Tournemire’s musical exploitation of chant that makes L’Orgue Mystique significant, but it is the exegetical elucidations that Tournemire evinced through chant, combined with his ability to educe within the heart of the listener the latent human intuitive ken of the Divine through his medium that makesit an artistic apogee in the realm ofsacred music. Indeed, Olivier Messiaen lauded Tournemire’s approach, stating that “one can hardly use the themes of plainchant more and better than Charles Tournemire in his L’Orgue Mystique.” (255)

Charles Tournemire à Sainte-Clotilde (1933)

Collect Marcel Degrutère

(Jean-Marc Leblanc, “Mémoires de Charles Tournemire: Édition critique,”

L’Orgue. 2018 I–IV, nº 321–324, page 273)

Musically, Tournemire sought to “clothe the Ideal in sensible form”; therefore, while drawing upon the liturgical texts, Tournemire called upon sonorous depictions of ecclesiastical architecture and oceanic imagery for which he had a great affinity. Throughout L’Orgue Mystique, Tournemire conjures euphonious representations of bells, incense, and the gleaming windows of stained glass. Paraphrase-carillon and Verrière [stained glass] are the most obvious examples of such elements, but there are also more obscure ones, such as when he referred (post hoc) to Alléluia nº V for the Eighth Sunday after Pentecost to be a representation of the rose window in the north transept of Notre-Dame in Paris. (319)

Seeing Gregorian chant and Gothic architecture as inextricably linked, Tournemire often quoted these aforementioned words of Huysmans: “Plainchant isthe aerial and mobile paraphrase of the immovable structure of the cathedrals.” (124) He further wrote of the conjoining of sacred architecture and chant:

If the Protestant chorale’s inestimable plastic value had inspired musicians of the stature of Scheidt and Bach, could not Gregorian chant, altogether richer, perhaps give birth to a new art supported by polyphony or polytonality? To penetrate this musical temple of the angelic lines necessitates prolonged religious and mystical preparation. The light, at first discrete, brightens faintly; but the addiction to the chant par excellence of the Church is an admirable thing. Imperceptibly, the soul is illuminated. A profound emotion is felt when an antiphon or an Alleluia is heard. Voilà, the door is open to the sonic edifice where the incense rises up. […] The Eternal entices to God a legion of Christian artists so that they purify contemporary art and carry this forth in knowledge and faith! (253)

L’Orgue Mystique is also rife with oceanic imagery. Tournemire summered at a cottage on the Île d’Ouessant, a small island at the end of an archipelago on the northwestern tip of France, where he would draw up plans for the compositions to be formally penned throughout the year when he returned to Paris in the autumn. Daniel Jean-Yves Lesur (1908–2002) recollected, “His love of nature was intense. Each year saw him carry back from

his retreat on the Île d’Ouessant one or another new chef d’œuvre, pondered while facing the ocean. The ocean’s presence marked his character with a sense of universal grandeur. The ocean and the cathedrals.” (178) Emanating from the chant texts themselves, he extrapolated symbolic correlations between natural phenomena and the Divine, peppering the work with sunrisings and settings, the stars at night, and the ocean waves. In Tournemire’s book on his teacher and predecessor at Sainte-Clotilde, César Franck (1822–1890) (which, in fact, was his manifesto on the creation of L’Orgue Mystique), the connection between his experience on the Île d’Ouessant and L’Orgue Mystique becomes clear:

Why should I hide my emotion while thinking that the Dispenser of Grace, indeed, wished to grant me that power to praise Him with simple musical prayers: L’Orgue Mystique? And why not add that I found therein the path which leads to the prayerful contemplation of unfathomable depths!

Let us contemplate the ocean! Does not its voice—great, deep, and sometimesterrifying— announce to us the majesty of the One who gives it life? Does one not see therein the image of life: the unleashing of the waves, the quelling, the infinite calm? Does it not sing—and with what loftiness—ceaseless and ever-changing hymns? When the wave breaks, how magnificent, and when it reaches the summit of a high rock, bursting forth its spray, let us give wonder and sing: “O come, let us sing unto the Lord: let us make a joyful noise to the rock of our salvation. Let us come before his presence with thanksgiving, and make a joyful noise unto him with psalms. For the Lord is a great God, and a great King above all gods. In his hand are the deep places of the earth: the strength of the hills is his also. The sea is his, and he made it: and his hands formed the dry land.” [Psalm xciv/xcv] (235)

Indeed, the Venite chant that cites Psalm xciv/xcv would become one of L’Orgue Mystique’s Leitmotifs, so the Île d’Ouessant haunts the work throughout.

Yet, these phenomenological elements are merely symbols pointing to that which is infinite and ineffable. Recollecting the beliefs of the Symbolists, we hearken back to the words of Moréas: “Thus, in this art none of the concrete phenomena are manifestations of themselves: these are rather the sense-perceptible appearances whose destiny is to represent their esoteric affinities with primordial Ideals.” Or as Péladan remarked: “Making the invisible visible: that is the true purpose of art and its only reason for existence.”

L’Orgue Mystique: Ann Labounsky Interview (Full Version)

Charles Tournemire: Photographie Henri Martinie, rue de Penthièvre, Paris

Collection Daniel-Lesur

(Jean-Marc Leblanc, “Mémoires de Charles Tournemire: Édition critique,”

L’Orgue. 2018 I–IV, nº 321–324, page 262)

The Language of Ineffability

The critic Norbert Dufourcq (1904–1990), in a 1938 article in La Revue musicale, wrote of Tournemire: “The great art of Charles Tournemire is one that appeals to an elite; it speaks to our sensitivity first, but it requires culture and effort from the listener.” (375)

As with all religious language, Tournemire’s music should not be taken as a mere aesthetic experience or a prima facie statement, representation, or definition, but rather as an asymptotic symbolic understanding of something that has an infinite ontology. To define—as its etymology suggests—is to denominate a finitude, which is a non-sequitur to the essence of that which is called God. As a kind of sonorous prosopopœia—giving voice to otherwise silent, immaterial, or non-anthropomorphic essences—the language of Tournemire’s music represents a euphonous evocation of religious symbolism, and these figural symbols are offered as adumbral images of an ineffable concept called upon in an attempt to define without being a definition—definiendum sans definiens—an exegetical device seeking to poetically entify the noumenal and suggest this is like as God. It is this hermeneutical quality and function—within and beyond the liturgy—that Tournemire believed to be music’s ultimate raison d’être.

Charles Tournemire: Photographie J. Vilatobá, Sabadell (Espagne), début julliet 1930

Collection Daniel-Lesur

(Jean-Marc Leblanc, “Mémoires de Charles Tournemire: Édition critique,” L’Orgue. 2018 I–IV, nº 321–324, 269)

Upon the publication of his Lyrical Ballads in 1807, that poetic harbinger of Romanticism, William Wordsworth (1780–1850), wrote in a letter to Lady Beaumont the following: “Every great and original writer, in proportion as he is great or original, must himself create the taste by which he is to be relished; he must teach the art by which he is to be seen.” (XXIII) With this in mind, time must be taken to elucidate the genius of Tournemire’s art and, indeed, the genius of art itself.

Dufourcq called Tournemire’s music “a sonoroussynthesis of the cathedral”, averring that he “has produced some of the most original conceptions to have emerged from the twentieth century.” (377–378) This is true, but to begin to understand Tournemire’s music, one must understand the language that he is speaking. Tournemire often cited these words of Ernest Hello: “Higher than reason, orthodox mysticism sees, hears, touches, and feels that which reason is incapable of seeing, hearing, touching, and feeling.” (125) It is through this language that Tournemire is communicating to us—that is, the Language of Ineffability.

Kilgen Organ Recital – Richard Spotts

About the Author

The organist Richard Spotts is the author of Charles Tournemire’s L’Orgue Mystique: La Haute Mission, which is a comprehensive study of French society and its relationship with the Catholic Church, the role of art in the conceptualisation of theological principles, and the personalities of the individuals that set these thoughts into motion, all of which formed important aspects of L’Orgue Mystique, which is given a thorough analysis of the two hundred-fifty-three-movement work. For more information on the book, visit the Leupold Foundation [https://theleupoldfoundation.org/product/spotts-richard-charles-tournemires-lorgue-mystique-la-haute-mission/].

Richard will be giving a complete performance of “L’Orgue Mystique” [https://richspotts.com/events/the complete-lorgue-mystique-by-charles-tournemire-2026/] in Philadelphia at Saint Paul’s Episcopal Church, Chestnut Hill [https://stpaulschestnuthill.org/], which is home to a culturally historic, newly restored Aeolian Skinner organ [https://stpaulschestnuthill.org/music/organ/] that is also the largest church organ in the city. This will be done as a seventeen-part series on the Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays of Lent 2026, from February 23rd through March 31st. For more information, visit richspotts.com.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter