Inspiration Behind James Matheson’s Windows

If you seek out the Union Church of Pocantico Hills in New York’s Hudson Valley, you’ll find a little gem. From the outside, it looks like a simple stone country church. When you get inside, however, it’s a whole new world of colour. The Rockefeller family, who held positions of importance in the United States from Vice-President of the country, to Governor of New York State, to heading Standard Oil, which is where they made their fortune in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was behind the unassuming building.

Union Church

The church was a gift from the Rockefeller family – they donated the land and assisted in the construction. The style inside the little church is austere: white walls and wooden pews, facing a plain altar. All of this was designed by French artist Henri Matisse between 1947 and 1951.

Union Church interior

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller died in 1946 and, as patron of modern art and a founder of the Museum of Modern Art, had been one of the first to champion Matisse in the US.

The church holds one window by Henri Matisse, a rose window that was the last work he designed before his death in 1954. At this point in time, Matisse was confined to his bed and was largely working with cutouts of paper. The commission brought out his final effort, and he wrote for the opening of the church: ‘…this work required of me four years of an exclusive and untiring effort, and it is the fruit of my whole working life. In spite of all its imperfections, I consider it my masterpiece’.

Following his design of the building itself, he was also convinced to design the rose window. Rose windows, located over the main door, are only seen when you leave the church.

Matisse: Rose Window

The work on the rose window was completed in 1956, under the supervision of Matisse’s daughter, and is dedicated to Abby Aldrich Rockefeller.

Nine years later, the great window at the end of the nave was installed. It was a memorial to John D. Rockefeller, Jr. the fifth child and only son of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. Junior (as he was known) was born in 1874 and died in 1960; Abby Aldrich Rockefeller had been his wife.

As Matisse was now dead, the family, as represented by Abby’s son David, approached Marc Chagall for the other windows for the building.

Created by Marc Chagall, the Good Samaritan window shows various stories within its frame: we see the man who was attacked and how the Good Samaritan carries him on horseback to help, a crucified Jesus, and a man climbing a ladder, who may be Jacob. The colours are rich and saturated, with the central flute being set off by reds, yellows, greens, and oranges.

Chagall: The Good Samaritan

The great window was installed in 1964. Chagall had been part of the refugee flood from war-struck Europe, saved by the Emergency Rescue Committee, which had been part-funded by the Rockefellers. He arrived in New York in 1941.

Following the Good Samaritan window, Chagall created the rest of the windows in the church. His next window was The Crucifixion, and then followed six Old Testament Prophets: Joel, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Daniel, Isaiah, and Elijah. The ninth window was dedicated to the Cherubim angels.

The Crucifixion window was installed in honour of Michael Rockefeller (1938–1961), who disappeared while exploring Dutch New Guinea (now part of Indonesia’s Papua region). The window, again with Chagall’s intense blue as the principal colour, ‘captures themes of memory and spiritual reflection’.

Chagall: Crucifixion

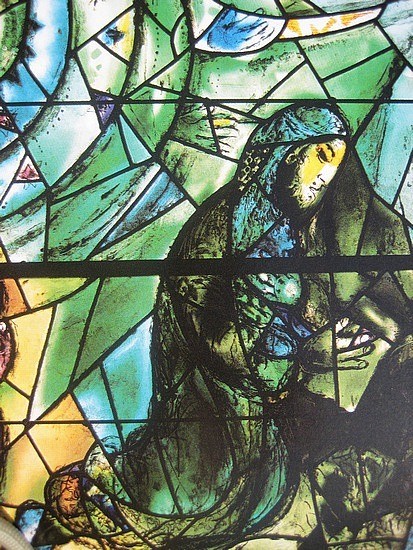

Joel, the second of the twelve minor prophets, whose dates are unknown, ranging from the 9th century to the 4th century BC. His name is given to the Book of Joel in the Bible, which contains a series of ‘divine announcements’. He reported on locust plagues and droughts, calling the locusts ‘God’s Army’ that is a call to national repentance. The intense blue glass is replaced by a gentler green colour.

Chagall: Joel

The prophet Jeremiah, author of The Book of Jeremiah, the Book of Kings, and the Book of Lamentations, warned of impending doom and was rejected by the Israelites. He’s shown in the window in a pose of deep contemplation.

Chagall: Jeremiah

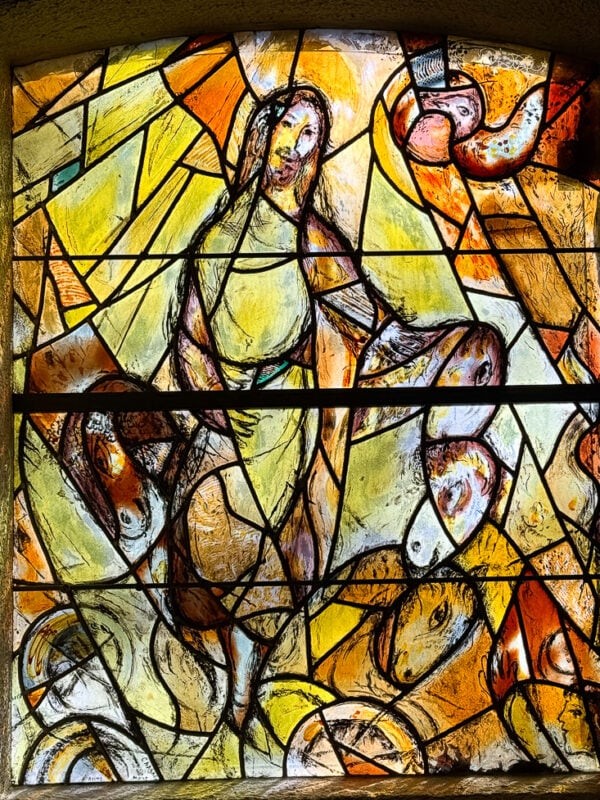

The prophet Ezekiel is shown receiving the Word of God from an Angel.

Chagall: Ezekiel

Another image in the muted tones seen in Ezekiel is the Daniel window. Daniel is shown being taken to heaven by the Archangel Gabriel. It is thought that the muted colours of this window were used to differentiate it from the Rose Window, at which Daniel’s hand points.

Chagall: Daniel

An angel with outspread wings covers the mouth of the Prophet Isaiah, who did not deem himself worthy of being a prophet. As a wealthy believer, his clothes show a more luxurious design than those of the other prophets.

Chagall: Isaiah

The last Old Testament prophet window is that of Elijah, shown ascending to heaven, with his disciple Elisha in the bottom right corner. Many of Chagall’s familiar animal figures are in the stained glass.

Chagall: Elijah

The last window is an unusual image of an angel. The Cherubim were one of the top orders of angels, charged by God to close the gates of Eden to Adam and Eve. They are often shown as forbidding angels, holding a flaming sword. In Chagall’s vision, the Cherubim window is a vision of hope and redemption. Its angel figures are shown as welcoming and of a more feminine aspect than usual.

Chagall: Cherubim

In 2016, American composer James Matheson created a work called Windows, based on five of the windows in the Union Church. He starts with Jeremiah, deep in the bass notes of the piano.

James Matheson (photo by Jamie Arrigo)

James Matheson: Windows – Jeremiah (Bruce Levingston, piano)

Isaiah, representing sacrifice, follows. It’s quick and kaleidoscopic with planes of sound substituting for planes of colour.

James Matheson: Windows – Isaiah (Bruce Levingston, piano)

The heart of the work, and, indeed, the heart of Christianity, is the still point of the Crucifixion. A momentous action has been taken that will change the world, and Matheson invites us to reflect on that. It’s a movement about loss and permanent change.

James Matheson: Windows – Crucifixion (Bruce Levingston, piano)

The Good Samaritan, on the other hand, is about the goodness in man and his altruism. The intricate patterns of the glass come to music as repetitive and evolving motifs. There’s something uplifting about the image and about the music.

James Matheson: Windows – The Good Samaritan (Bruce Levingston, piano)

As befits a work that is only seen as you exit the church, the final movement is The Rose. Organ-like sonorities gradually change until we come to the final peaceful notes.

James Matheson: Windows – The Rose (Bruce Levingston, piano)

Chagall’s ornate and colourful windows are set off by the simplicity of Matisse’s design for the plain white church. James Matheson composed Windows to celebrate the centennial of the Union Church of Pocantico Hills and the centenary of the birth of David Rockefeller.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Thank you publishing this piece. The music and the art and the design of the church are awesome, in the older sense of the word.