Recorded on 30 May 2023, the Orchestre de Paris under Klaus Mäkelä invited Sol Gabetta and Willard White for a programme featuring selected works by Shostakovich and Walton.

Dmitri Shostakovich © Deutsche Fotothek

Shostakovich and Walton, two composers separated by geography but united by the turbulent pressures of their time, wrote music that speaks in sharp contrasts, hidden tensions, sudden lyricism, and flashes of biting irony.

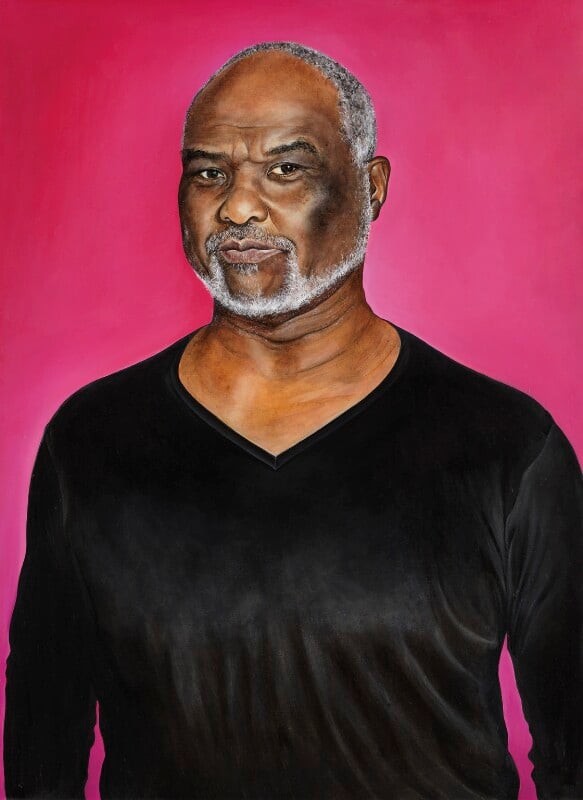

William Walton

Under Mäkelä’s baton, and with Gabetta and White as narrative guides, these works unfold not simply as performances, but as encounters. They provide windows into the complexity of the 20th century and into the expressive power of artists who refused to look away.

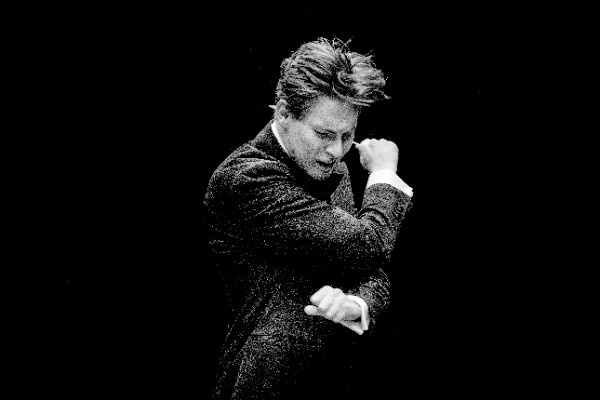

Klaus Mäkelä conducts Shostakovich and Walton

A Dance through Time

Klaus Mäkelä

Shostakovich’s Suite for Jazz Orchestra No. 2 dates from 1938 and was composed for the newly founded Soviet State Jazz Orchestra. It offers a rare glimpse into the composer’s lighter and more playful side.

With the orchestral parts vanishing during World War II, the suite lay dormant until a piano sketch was rediscovered in 1999. A reconstruction quickly followed and allowed the modern audience to partake in a stylised, orchestra and theatre-influenced homage to popular dance forms.

In a concert setting, especially under a modern conductor with a flair for colour and contrast, this suite can serve as a light-hearted yet poignant prelude. A palette cleanser, if you wish, or a witty interlude before plunging back into the deep emotional waters of Shostakovich’s more serious works.

From Levity to Confrontation

By contrast, the 2nd Shostakovich Cello Concerto, composed in 1966 at a late stage in the composer’s life, reveals his most introspective impulses. Structured in three movements, the concerto departs from traditional concerto bravura in favour of sombre reflection, expressive restraint, and haunting atmospheres.

As the concerto unfolds, Shostakovich weaves in grim irony, grotesque distortions, and moments of biting satire in the form of familiar friends-like horn calls, elegant baroque-style gestures, or dance-like motifs. Yet, as soon as they emerge, they become twisted, repeated, or disruptive.

Ultimately, the concerto does not resolve into triumph, but ends quietly, essentially a chilling reminder of endurance, memory, and loss. In this programme, together with the Jazz Suite, it stands as a dark counter-weight. It is a journey from levity to existential confrontation, from public entertainment to deeply personal testimony.

Grandeur and Pathos

Willard White

Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast, the work featured in this concert with bass-baritone Willard White, is a striking example of his gift for drama and orchestral colour. Composed in 1931 and immediately acclaimed for its boldness, the cantata sets the Old Testament story of King Belshazzar’s downfall to vividly expressive music.

Walton’s scoring is richly textured, combining choir, soloist, and full orchestra to convey both grandeur and intimate psychological nuance. The work moves effortlessly between the terrifying and the lyrical, where solo lines soar with unexpected tenderness.

Unlike Shostakovich’s Jazz Suite, with its playful levity, Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast occupies a more monumental and theatrical space, yet it shares with the Cello Concerto an embrace of emotional extremes. The music alternates between tension and release, irony and pathos, highlighting Walton’s skill at balancing narrative momentum with musical invention.

Placed alongside Shostakovich in the same programme, Walton’s work underscores the evening’s exploration of 20th-century contrasts. Both composers respond to turbulent times with music that can shock, delight, and move in equal measure, yet where Shostakovich often blends irony with introspection, Walton’s vision is more overtly theatrical and more overtly heroic.

Between Charisma and Critique

Sol Gabetta © Kaupo Kikkas

Mäkelä’s approach in this concert appears emblematic of his broader leadership style, as he offers a blend of vivid colouring, dramatic flair and a willingness to embrace contrast and emotional extremes.

However, critical and broader opinions about Mäkelä’s style, especially in light of this concert and his other recent engagements, remain somewhat divided. While many reviewers praise his technical command and his ability to draw bold playing from his ensembles, others argue that his interpretations sometimes lack deeper stylistic insight.

One reviewer, writing in a different context, described a Shostakovich performance as “characterless,” arguing that they fail to convey the composer’s irony, sarcasm, or emotional urgency, and thereby reducing the music to technically competent but emotionally bland renditions.

In my personal view, Mäkelä is a modern celebrity-conductor, but for all his skill and charisma, he has yet to prove that his strong first impression can translate into the kind of deep and enduring interpretive identity that sustains a long career.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter