On 17 September 2025, conductor Riccardo Minasi, flautist Emmanuel Pahud and the Radio France Philharmonic Orchestra joined forces for a concert dedicated to Mozart, Schubert and Mendelssohn, with a Debussy encore.

At the heart of the program is Mozart’s Flute Concerto No. 1 in G major, K. 313 (1778), written during the composer’s frustrating sojourn to Mannheim and Paris. Commissioned by the Dutch amateur flautist Ferdinand De Jean, a surgeon in the Dutch East India Company, this concerto is one of Mozart’s most beloved wind works.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Mozart’s dislike for De Jean is well documented, but the idea that he hated the flute is one of the most persistent myths in classical music. Pahud convincingly demonstrated that Mozart’s flute music, so often dismissed as charming ornament, is in fact a well of astonishment.

Riccardo Minasi with Emmanuel Pahud

Emmanuel Pahud

Emmanuel Pahud © Stefan Höderath

Emmanuel Pahud, born in Geneva in 1970, is widely regarded as one of the leading flautists of his generation, celebrated for his technical brilliance, tonal beauty, and interpretive depth. He studied at the Conservatoire de Paris, quickly earning a reputation for exceptional musical sensitivity, and in 1992, he became principal flautist of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra.

Beyond the orchestra, Pahud has forged a distinguished solo and chamber career, recording the works of composers from Mozart and Bach to Ibert. His interpretations are noted for their “singing tone, clarity of phrasing, and imaginative ornamentation,” bringing warmth, humour, and depth to music often dismissed as delicate or superficial.

Through his artistry, Pahud has not only elevated the flute to unprecedented heights of technical and expressive sophistication but also reshaped the way audiences experience its music. Revealing music’s capacity for lyricism, wit, and emotional depth, Pahud transforms compositions often considered ornamental into profound, living statements.

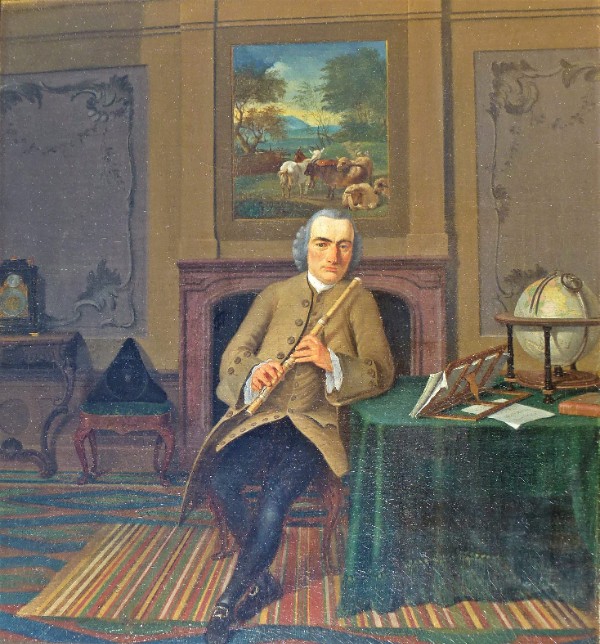

Mozart and De Jean

Ferdinand De Jean

During his stay in Mannheim from late 1777 to early 1778, Mozart entered into a commission agreement with the wealthy Dutch amateur flautist Ferdinand De Jean via the Mannheim court musician Johann Baptist Wendling. De Jean offered Mozart 200 gulden for “three small, easy and short concertos and a couple of quartets for the flute.”

Mozart accepted, probably seeing both the artistic opportunity and financial benefit. However, the relationship between composer and patron proved complicated. Mozart completed only two concertos, the Flute Concerto in G major, K. 313, and what became the D-major concerto, K. 314, a reworking of his earlier oboe concerto, plus an Andante in C, K. 315, rather than all three originally promised.

Financially, Mozart was not fully paid. He received just 96 gulden of the 200 promised, which clearly frustrated him and his father. Mozart’s correspondence reveals a mixture of artistic reluctance and personal irritation with the commission.

In a letter to his father from Mannheim dated 14 February 1778, he wrote that he “becomes quite powerless whenever I am obliged to write for an instrument (flute) which I cannot bear,” but scholars argue that his particular comment was coloured by the stress of travel and the strain of an unpaid commission.

Pahud and Mozart

Riccardo Minasi

Emmanuel Pahud brought unparalleled authority and artistry to this performance of the Mozart concerto as he embodied the Mozartian spirit with both mischievous sparkle and profound lyricism. The opening “Allegro maestoso” unfolds with swirling virtuosity, yet the phrasing remains coherent and daringly free in rhythm.

Technical mastery is evident in every detail as breaths synchronised seamlessly, and scales and ornaments are executed with astounding precision. Add to this articulation that balances elegance with vitality.

The “Adagio non troppo” offers a masterclass in legato and expressive control. Pahud’s playing is enveloping and eloquent, exploring the flute’s full tessitura with hushed pianissimos and warm, resonant fortes, all while avoiding sentimental excess.

The finale, a spirited “Rondo,” bursts with fiery energy. Articulations are varied and lively, evoking a playful dance, which Riccardo Minasi’s conducting supports impeccably. Minasi maintains clarity and bounce in the orchestral accompaniment, ensuring the soloist remains at the centre without ever being overshadowed.

Humanity, Profundity, and Dreamlike Surrender

Radio France Philharmonic Orchestra

Ultimately, the concert’s great appeal, also featuring Schubert’s “Overture in the Italian Style,” and excerpts from Mendelssohn’s incidental music to “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” lies in Emmanuel Pahud’s interpretation of Mozart.

Pahud’s Mozart is transcendent, not merely technical, but deeply human. In this repertoire often reduced to a pleasant background, Pahud reminds us of its profundity. As an encore, Pahud performed Claude Debussy’s Syrinx, a solo masterpiece originating in the theatre. From luminous awakening to shadowy introspection, Pahud evoked a sense of dreamlike surrender.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter