November 14 saw a world premiere at San Francisco Opera: Huang Ruo’s The Monkey King, with a libretto by David Henry Hwang, based on Journey to the West, 16th-century multi-volume epic attributed to Wu Cheng’en. Running through November 30, with a livestreamed performance briefly available for on-demand viewing (on which this review is based), the opera is a brilliant combination of the best in new music, the best in Chinese and Western stage traditions, and the best of modern theatre technology. I viewed the opera via the live stream from San Francisco Opera, rather than in person, which would have made it even more spectacular.

The Monkey King is a character-type found in every mythology: the disrupter who ruins your best-made plans and has his own way—in short, chaos personified. He’s Loki, he’s Kokopelli, he’s Hermes, just to cite a few of his many guises.

The Puppet Monkey King born of a stone

In this account, the Monkey King, having been in captivity for 500 years, tells his story of being born from a stone and winding up imprisoned. In between, he seeks power and nobility and, in the process, wreaks havoc on several worlds.

The Three Kings

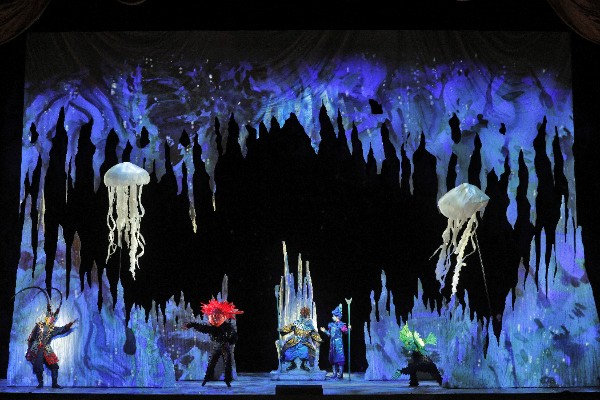

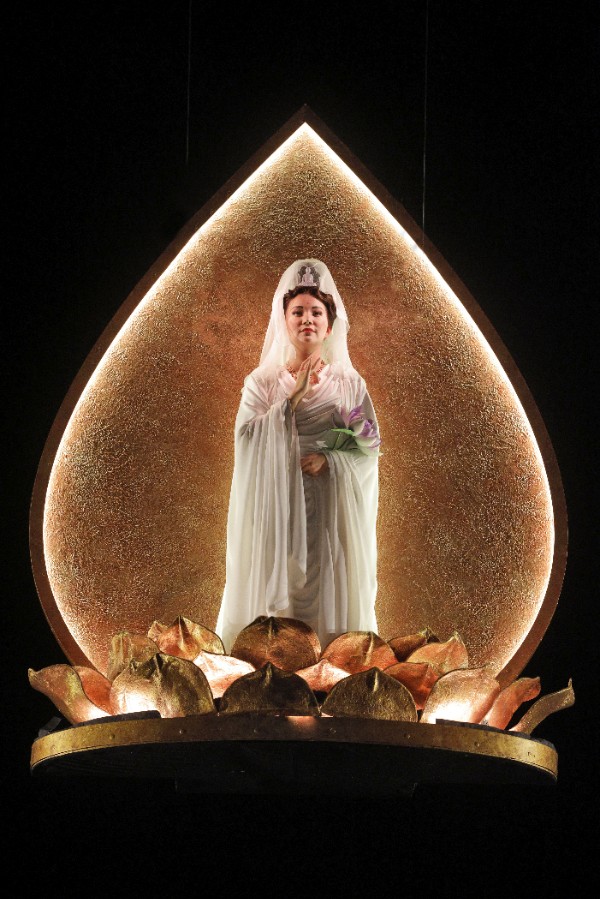

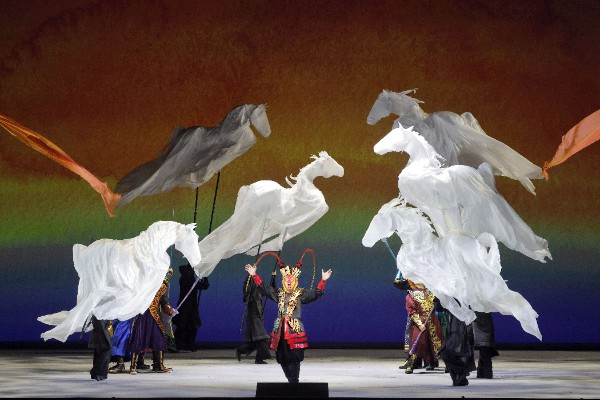

The Monkey King is portrayed on stage by three actors: Kang Wang (tenor), Huiwang Zhang (dancer), and a half-size puppet. The play, in fact, is full of puppets, designed by Basil Twist and manipulated in various Asian styles: by hand or on sticks, by puppeteers in invisible black. Everything floats: clouds, the Jade Emperor’s horses, jellyfish, the Buddha and the goddesses, even the Monkey King (in his dancer mode).

The Dancer Monkey King at the court of Master Subhuti

The Buddha’s lesson for the Monkey King is always the same: Power Alone is Not Enough. At the end of the opera, though, we learn the key word in that sentence is not Power, but Alone. He must bring other people along on his journey.

Little details like this are what make this performance work so well: the effortless trading among the three Monkey King players; Monkey’s discarding of various weapons as being ‘too light’, the fake fashionable look of the courtiers in Heaven proclaiming their coolness, the chorus at the end holding Imperial clouds, and so many other scenes.

Monkey King underwater

Huang Ruo’s music unfolds in many different styles, ranging from bang-a-gong Chinese opera sonorities to modern minimalism, to contemporary symphonic styles. Much of his outstanding writing is done for the goddess Guanyin, who takes it upon herself to support Monkey through his trials, appearing as necessary floating through the air on her lotus throne.

Guanyin in her lotus

The heart of the opera is the defeat of the Jade Emperor and his minions. Guanyin claims they have become complacent and uncaring and, although the Jade Emperor quickly agrees to change his ways, his general corruption sets himself up for his downfall.

The Monkey King is brought to heaven with a seemingly high-ranking title (Master of the Stables) and finds that his charges are unhappy. The new stable master sympathizes: ‘They treat you like beasts who live only to serve. Because you are different, they think you are lesser,’ and then realizes that he is being treated the same way. Finding himself duped, he frees the Emperor’s discontented horses in one of the most wonderful set-pieces of the opera.

The Jade Emperor’s Horses are loose

Confronted by the Jade Emperor’s minions, he defeats them all, often using their own weapons. The dance battle between the Dancer Monkey King and the Dancer Lord Erlang brings numerous elements into the fight, including stock Chinese opera battle sequences and shape-shifting transformations, concluding in a triumph for the Monkey King.

Sons of the Jade Emperor behind Lord Erlang

This is a 21st-century opera different from all others. Not only were all its performances sold out, but Huang Ruo finally delivered the music we’ve been waiting for. His aria for Guanyin, ‘All dharmas are equal’, cuts to the opera’s heart and brought its own ovations. Ruo’s earlier operas, such as Dr. Sun Yat Sen (2011, r/2014) lack the power and delivery we can hear in this work. It helps that Ruo is collaborating with a more accomplished librettist, David Henry Hwang, who has been fighting the good fight for Chinese representation on the stage. Hwang has worked with several other composers, most notably Philip Glass.

The story is tight and concise; the only bits that drags on are the multiple verses where the Jade Emperor’s courtiers self-proclaim their coolness but look like a bunch of out-of-touch oldsters. But maybe that was the point.

The Court of the Jade Emperor

The Monkey King is constantly mis-named: the Dragon King calls him ‘Monster King’ and ‘baboon’, the Jade Emperor calls him a ‘barbarian’ and ‘not even human’. All complain he is out of control and needs to be stopped, but later we find out that his master has sent him out to be a deliberate trouble-maker. He is recruited (in vain) as a ‘model inferior’ to placate the masses, but in the end it’s the Monkey King displaying humane compassion, tirelessly defeating all who threaten his fellow monkeys (whom he dubs his “children”). Despite his many transgressions, and the late realization that his Master Subhuti is really the Buddha, the Monkey King still maintains the support of Guanyin, who considers him redeemable (despite much evidence to the contrary).

This opera draws only on the first seven chapters of the 100-chapter Journey to the West. As the novel continues, after his 500-year imprisonment, the Monkey King is recruited to travel with the monk Tang Sanzang to India in search of authentic Buddhist sutras to bring to China. They are accompanied by Pigsy, Sandy, and White Dragon Horse, each travelling in atonement for problems they caused in the world.

The Monkey King in his Phoenix-Winged Feather Crown

Perhaps the whole opera is an object lesson for modern America: that the leadership is corrupt and self-focussed, ignoring all those not in its inner circle, and regularly turning to heaven for the aid it is incapable of providing itself. It’s the Monkey King and other ‘inferiors’, though, who rise to overthrow the corrupt leaders and return to the original teachings (which I take to mean the US’s much-abused Constitution rather than the teachings of Buddha). The calls for those in power to exercise their feelings of compassion won’t fall on deaf ears. But who will be our Monkey King?

Huang Ruo: The Monkey King

San Francisco Opera

November 14–30, 2025

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter