Have you ever browsed a classical music program and wondered what all those cryptic numbers mean? BWV 988? K. 550? Sz. 106?

Well, you’re not alone. Many music lovers don’t know what they mean!

But these catalogue numbers are more than just academic trivia. They’re essential tools for identifying and organising the works of composers like Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Bartók, and many other composers.

Today, we’re exploring the origins and meanings behind the most common classical music catalogue systems, from Bach’s BWV numbers to Bartók’s Sz. numbers, and explain how they help performers, scholars, and listeners make sense of composers’ vast musical outputs.

Whether you’re a seasoned aficionado or a curious newcomer, understanding these numbers will deepen your appreciation for classical music’s rich history.

What Does Opus Mean?

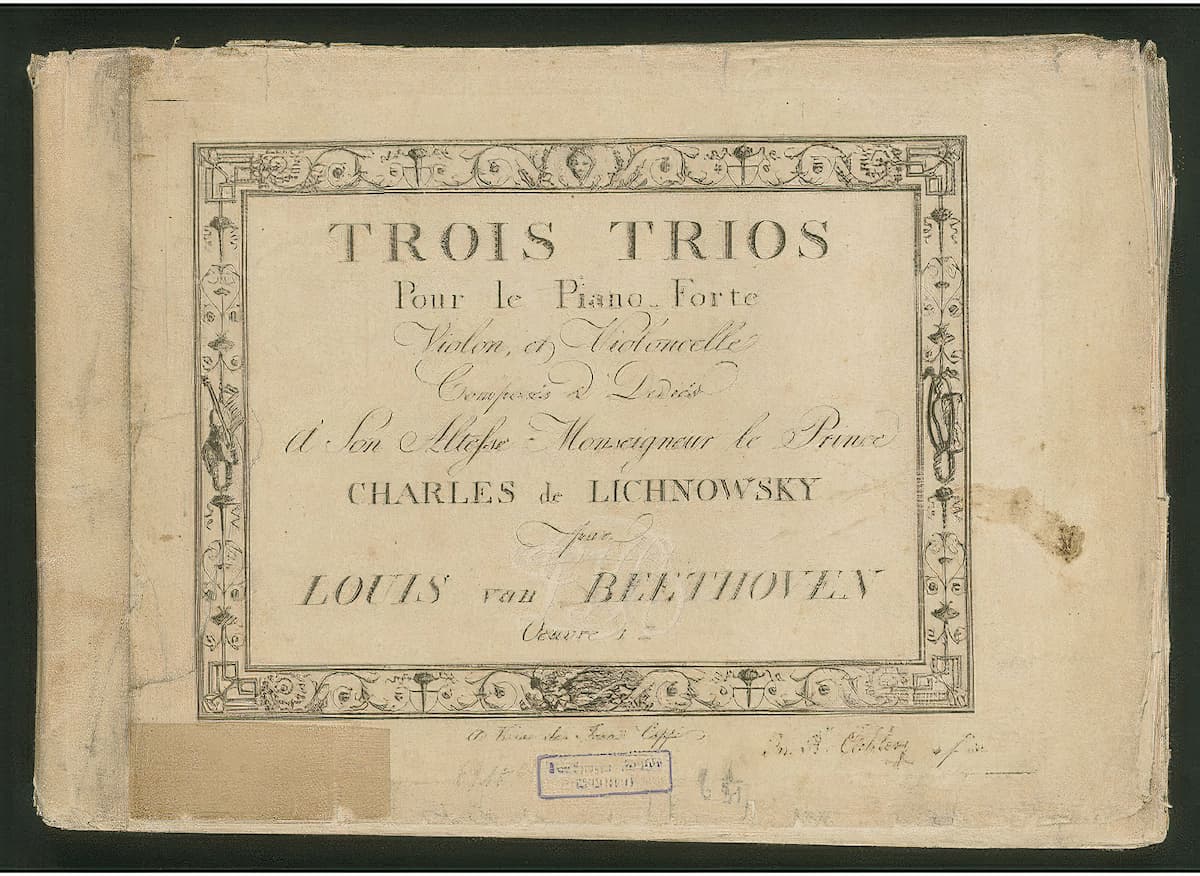

Beethoven’s Piano Trio Op. 1 cover page

Let’s start with the big one: what does the word opus mean in classical music?

Opus is Latin for “work.”

In the early 1700s, when it became common to publish groups of like works together, publishers issued editions with “opus numbers” attached to differentiate them and also indicate what order those works had been published in.

For example, Beethoven’s Opus 18 consists of six string quartets.

- The first is referred to as Beethoven’s Opus 18, Number 1

- The second is referred to as Beethoven’s Opus 18, Number 2

- The third is referred to as Beethoven’s Opus 18, Number 3

- And so on.

You can read more about “How music is catalogued”.

What is an opus?

However, opuses only covered published works. What to do with music that was never published? Or what happens if you want a list of works in the order they were written, not published?

These limitations to the opus number system are why we have composer-specific catalogues.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750)

BWV numbers

Bach’s Cantata Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, BWV 140

Bach composed his works before the use of opus numbers became widespread.

For that reason, scholars have assigned his works BWV (Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis, or Bach Works Catalogue) numbers.

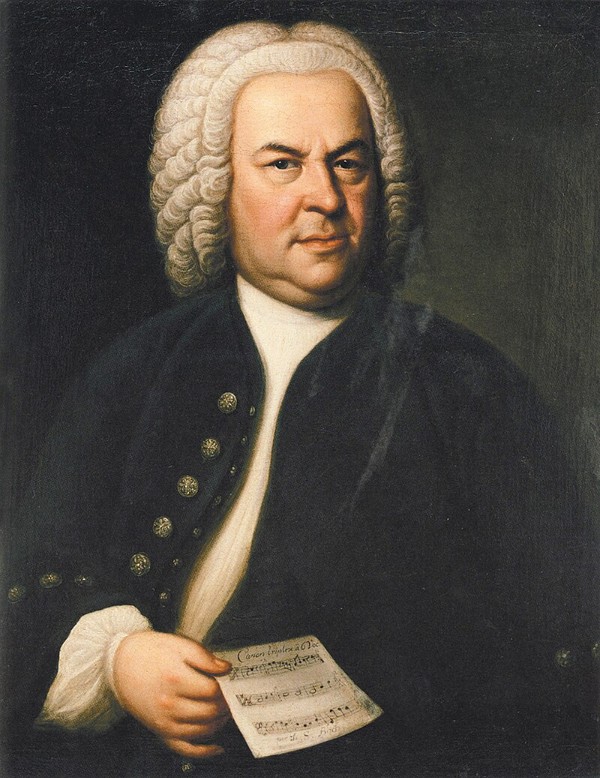

Elias Gottlob Haussmann: J.S. Bach, 1746 (Leipzig: Bach-Archiv)

The first scholar to assign numbers to Bach’s works was German music librarian Wolfgang Schmieder, who catalogued them between 1946 and 1950.

We don’t know the exact dates when many of Bach’s works were written, so Schmieder chose to group them by type instead.

For example, his cantatas are numbered BWV 1 through BWV 224; his motets are numbered BWV 225 to BWV 331; and so on.

Joseph Haydn (1732-1809)

Hoboken numbers

Haydn’s String Quartet in F-minor, H. III:35

Dutch musicologist Anthony van Hoboken spent the years between 1934 and 1978 assembling a catalogue of Haydn’s works.

Hoboken had been born into wealth, which allowed him to pursue his academic studies without the need to earn a living. He could also use his money to collect and preserve rare musical manuscripts, including a jaw-dropping 1000 manuscripts by Haydn alone.

Joseph Haydn

He chose to sort them by type, not chronologically. Unlike other catalogues, he employed Roman numerals at the beginning. Symphonies start off with the numeral I; string quartets start off with the numeral III; concertos start off with the numeral VII.

Therefore, in this catalogue…

- Symphonies are labeled H. I:1 to H. I:108

- Divertimenti in 4 and more parts are labeled H. II:1 to H. II:47

- String quartets are labeled H. III:1 to H. III:83

- And so on.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

Köchel numbers

Mozart’s Piano Sonata, K. 545

Austrian musicologist Ludwig Ritter von Köchel (1800–1877) earned a PhD in 1827 and became the private tutor of the children of Archduke Charles of Austria, a son of Emperor Leopold II.

He was rewarded for his services with financial support. This created personal wealth that allowed him to spend his life pursuing his academic studies without having to hold down a traditional job.

Robert Greenberg’s podcast episode on Ludwig Ritter von Köchel

In 1862, Köchel published his Chronologisch-thematisches Verzeichniss sämmtlicher Tonwerke W. A. Mozart (“Chronological-thematic Catalogue of the Complete Musical Works of W. A. Mozart”).

He set a daring goal for himself: to catalogue Mozart’s hundreds of works chronologically, rather than arranging them by type.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

As you can imagine, as new works are discovered or reattributed, the catalogue changes. Since 1862, there have been nine editions.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

WoO and H. numbers

The works of Beethoven are classified using three different kinds of numbers.

First are the opus numbers assigned by his publishers. These go in order of publication.

Second are WoO numbers. This abbreviation stands for “Werke ohne Opuszahl” (or “Works Without Opus Numbers”). These are works that never received an opus number because they were never published.

To make things extra confusing, the WoO catalogue is also known as the “Kinsky-Halm Catalogue” after the two men who initially created it, Georg Kinsky and Hans Halm.

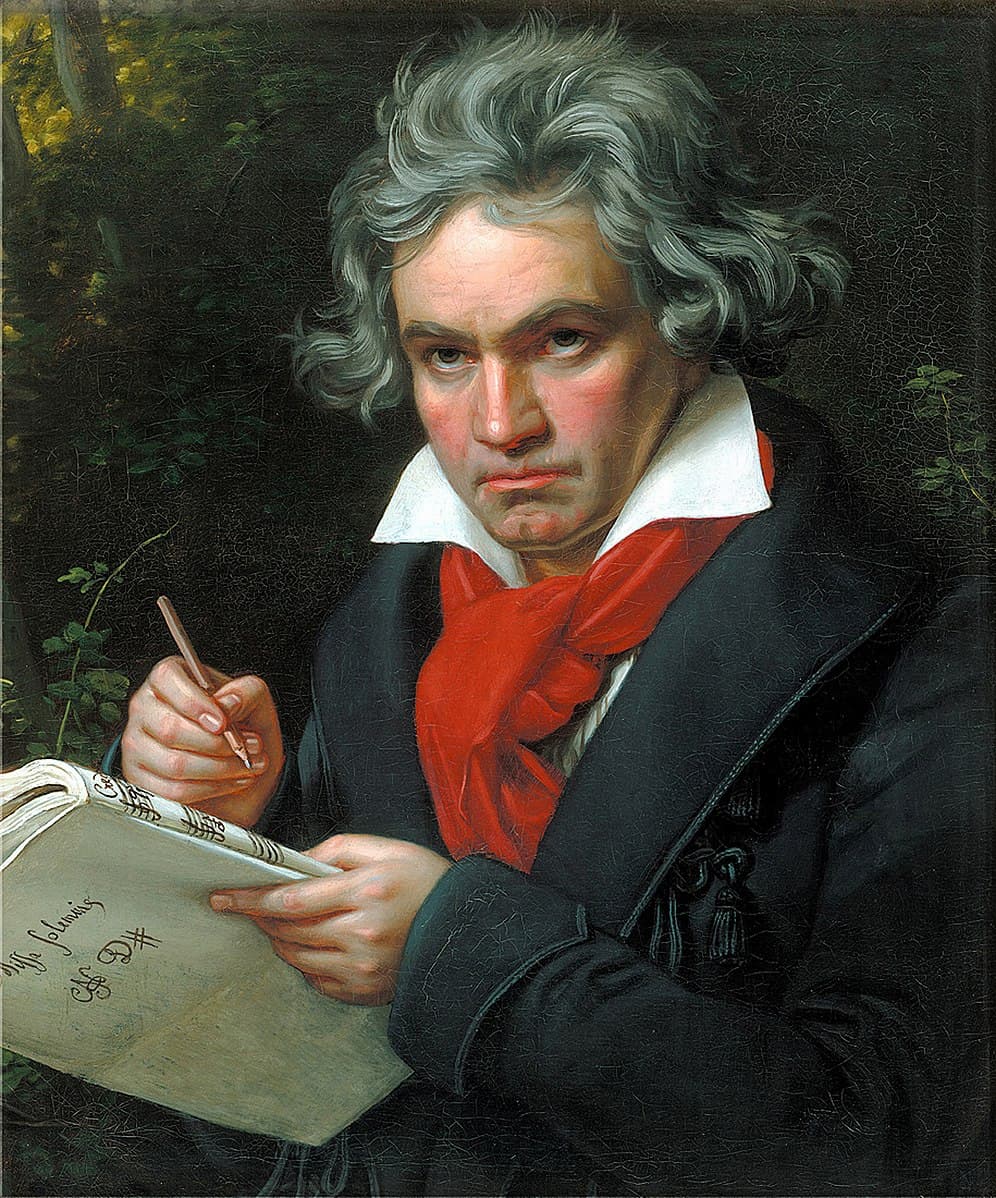

Portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven

Georg Kinsky (1882-1951) was a German musicologist. He was the son of a Jewish businessman and was sent to a labour camp during World War II. Fortunately, he survived the war, and he spent the final six years of his life assembling the catalogue.

Fellow German musicologist Hans Halm (1898-1965) finished the catalogue after Kinsky’s death, publishing it in 1955.

Beethoven’s Für Elise, WoO 59

In order to understand the third kind of number, you have to know about the Beethoven Gesamtausgabe (or, loosely translated, Complete Guide to Beethoven), which was a collected edition of Beethoven’s works that was published in the 1860s.

It quickly became clear that the collection was rife with errors and limitations, and didn’t actually contain everything that Beethoven wrote. Edits were badly needed.

Enter Swiss composer and musicologist Willy Hess (1906-1997). Willy Hess decided to catalogue Beethoven’s works by assigning numbers to works that didn’t appear in the Gesamtausgabe. He worked on this project from 1959 to 1971.

This is why today Beethoven’s works may be listed with an opus number, WoO number, or H. number.

An interesting side-note: a complete edition of Beethoven’s works is currently being assembled by the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn, but the project has been ongoing since 1961 with no end date in sight. Of the projected 56 volumes, only 43 have been published!

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

D. numbers

Many of Franz Schubert’s works were unpublished during his lifetime, so cataloguing his entire output can be especially challenging.

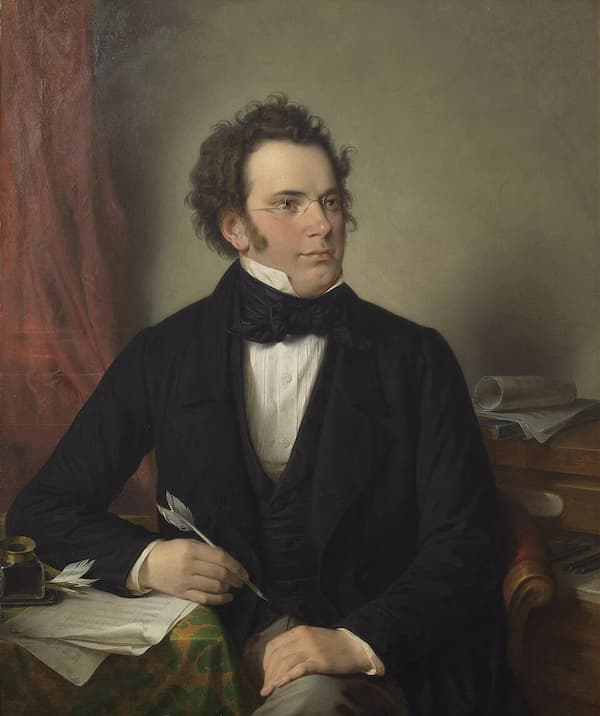

Wilhelm August Rieder: Franz Schubert, oil painting (1875) after an earlier watercolour (1825) (Vienna Museum)

Austrian musicologist Otto Erich Deutsch (1883-1967) was the one who took on the challenge.

Deutsch was a music librarian who worked for Anthony van Hoboken, the millionaire who catalogued Haydn’s works.

Deutsch’s family background was Jewish, so in 1938, he fled the Nazis and worked in England until 1951, when he returned to Vienna. During his exile, he buried himself in studies of Schubert.

In the year of his return to Vienna, he published the Schubert Thematic Catalogue, which listed and numbered all works by Franz Schubert.

Today, musicians performing Schubert identify works by the Deutsch number, which is abbreviated as D. number.

Schubert’s Fantasy for Piano 4 Hands, D.940

Closing Thoughts

Hopefully this new information helps you navigate finding, listening, and performing these works. In the end, don’t get too hung up by catalogue numbers, though. Even many seasoned classical music lovers don’t know exactly what they mean!

Composers’ outputs continued to be assembled after Schubert. In our companion entry, we’re looking at how Chopin, Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Debussy, and others have had their works catalogued.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter