For many listeners, the Second Viennese School conjures fear rather than affection—a fog of theory, numbers and atonality. The truth is far richer. These composers charted one of the most fascinating journeys in musical history, from the emotional heat of late Romanticism to lean, crystalline modernism. Here are ten pieces to guide you on that journey, step by step.

1. Anton Webern: Langsamer Satz (Slow Movement) (1905)

We begin not with a manifesto, but in the warm afterglow of Wagner and Mahler. Drink from Webern’s wells of Tristan-like chromaticism, lush inner voices and ecstatic phrasing. No one hearing this music blind would guess its composer would one day fit an orchestra into a matchbox. Hear the emotional lineage first; it makes what comes next intelligible.

Anton Webern: Slow Movement (Quartetto Italiano, Ensemble)

2. Alban Berg: Piano Sonata, Op. 1 (1908)

Berg’s first published work is a passionate one-movement sonata that sounds as if it’s perpetually yearning. At times tonal, it constantly slips its moorings, feeling like Mahler heard in a dream. Focus on the melody at first, which is almost always the highest pitch in this piece. It may take several hearings to get used to the melodic leaps and textural complexity, but soon you’ll feel its aching gestures and emotional turbulence. Berg’s fingerprints—tragic sighs and crashing crescendos—never left his music.

Alban Berg: Piano Sonata, Op. 1 (Daniel Linder, piano)

3. Berg: Altenberg Lieder, Op. 4 (1912)

Settings of aphoristic postcard texts by the Bohemian modernist Peter Altenberg, these five songs precipitated a riot so intense that its 1913 premiere was named the Skandalkonzert. It’s difficult now to understand their ability to shock. Berg ignites glittering orchestral colours in these miniature emotional worlds, one minute languorous and the next explosive.

Renée Fleming sings the Altenberg Lieder, Op. 4,

with Claudio Abbado conducting the Lucerne Festival

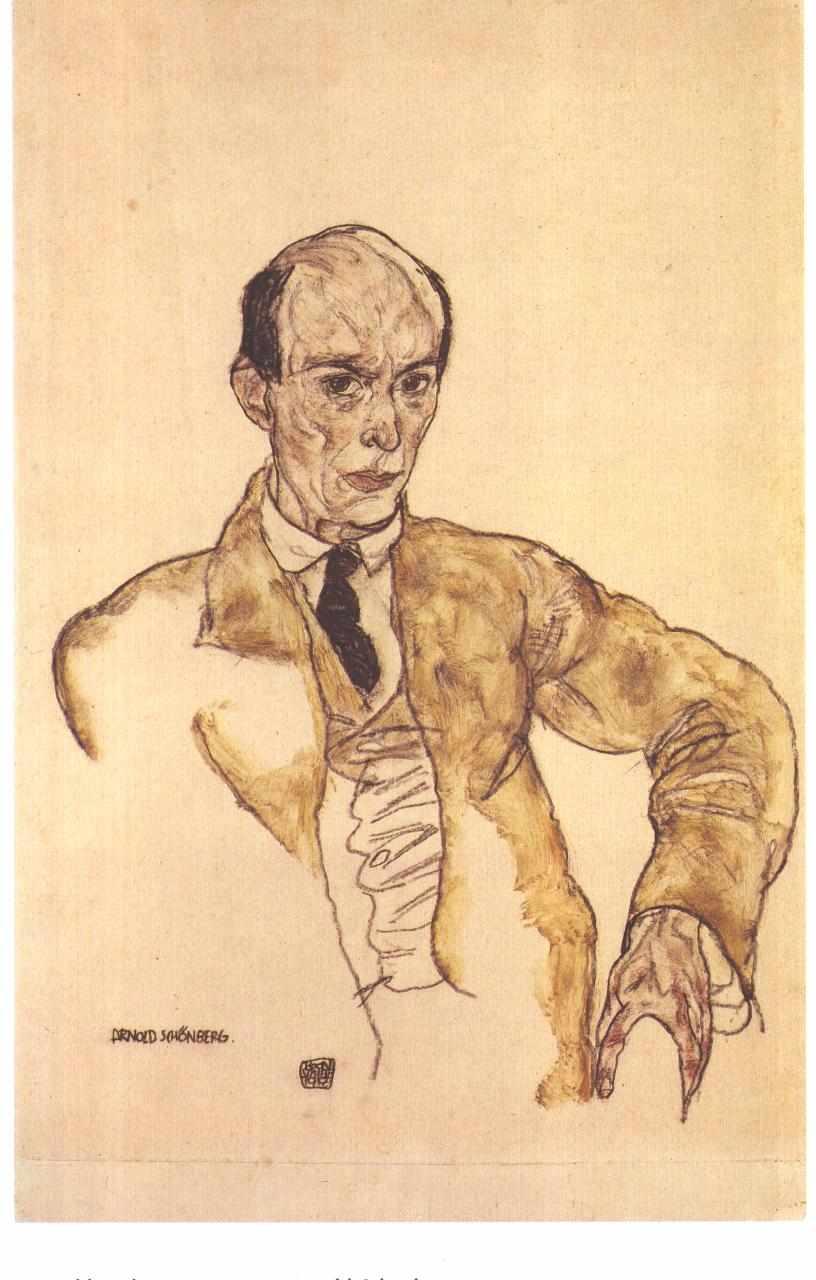

Alban Berg painted by Arnold Schoenberg (1910)

4. Arnold Schoenberg: Five Pieces for Orchestra, Op. 16 (1909)

Here, the tonal tether finally snaps, but into a burst of colour rather than chaos. Each movement paints a sound-picture. In the third, Farben, a single harmony drifts through the orchestra as instruments vary the lighting from flute to horn to harp, like a sunrise refracted in water. Think of it as Monet’s Water Lilies rendered in orchestral colour. Klangfarbenmelodie—colour-melody—is born, yet the triad remains, a life-raft in new seas.

Daniel Barenboim conducts the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in Farben

Arnold Schoenberg, painted by Egon Schiele (1917)

5. Schoenberg: Pierrot Lunaire, Op. 21 (1912)

A delirious carousel of poems for voice and five players on eight instruments, Pierrot Lunaire is grotesque and witty, Viennese and futuristic. Its half-sung, half-spoken delivery—sprechstimme, Schoenberg called it—may seem strange at first, although Rex Harrison used a similar technique on the London stage for the original My Fair Lady. Imagine the music’s bite and emotive exaggeration in a Weimar cabaret or with an early expressionist horror film.

Soprano Kiera Duffy and pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard, with members of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Cristian Macelaru, perform Pierrot Lunaire

6.Berg: Violin Concerto (1935)

Often called the most accessible masterpiece of the atonal world, Berg’s concerto is a requiem for Manon Gropius, imbued with an unbearable and beautiful sense of loss. Within his serial structure, Berg makes the poignant choice to weave in a Carinthian folk tune and a Bach chorale (Es ist genug), creating heartbreaking beacons. In this deeply emotional, tragic, and ultimately transcendent work, twelve-tone technique is a carrier for profound human expression.

Alban Berg: Violin Concerto – I. Andante: Allegretto (Arabella Steinbacher, violin; Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra; Andris Nelsons, cond.)

7. Webern: Six Bagatelles for String Quartet, Op. 9 (1913)

Tiny revelations—some movements last under half a minute—these fragments condense a lifetime of feeling into a few hushed gestures. Every note is essential, and silence becomes eloquent. The Bagatelles reward close, meditative listening.

Quartetto Italiano plays the Webern Bagatelles:

Schoenberg photographed by Man Ray (1927)

8. Schoenberg: Violin Concerto (1936)

If Berg’s Violin Concerto is an elegy, Schoenberg’s is a muscular drama. The solo line is a continuous, cadenza-like outpouring, by turns lyrical, assertive and virtuosic. Follow the argumentative energy, the way the violin duels with, emerges from, and is swallowed by the orchestral texture. It is a colossal, intellectual summit, but one that offers breathtaking vistas.

Arnold Schoenberg: Violin Concerto, Op. 36 – I. Poco allegro (Hilary Hahn, violin; Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra; Esa-Pekka Salonen, cond.)

9. Berg: Lulu Suite (1934)

Before his unfinished opera Lulu could be staged in its entirety, Berg extracted five movements into a concert suite. It is a stunning, self-contained portrait of an amoral, captivating heroine. The suite moves from the slinky, jazz-inflected rhythms of the Rondo to the terrifying, expressionist cry of the Lied der Lulu, where the soprano voice soars in a declaration of selfhood. The heart of the work is the Variations, a passacaglia built on a single, descending bass line that serves as a requiem for Lulu’s victim. The same music that depicted Lulu’s rise paints her gruesome death at the hands of Jack the Ripper. Lulu is a masterpiece of musical storytelling, where complex technique serves a narrative of devastating emotional power.

Alban Berg: Lulu Suite – I. Rondo: Andante und Hymne (London Symphony Orchestra; Claudio Abbado, cond.)

10. Webern: Symphony, Op. 21 (1928)

Just two movements and ten minutes long, Webern’s Symphony distills everything—structure, colour, proportion—into gleaming precision. Built from a single twelve-tone row, it sounds as serene and transparent as a pointillist painting.

The second-movement Theme and Variations are the summit: a six-note row mirrored, inverted, and retrograded in palindromic perfection, yet the variations sing like a distant folk dance. Imagine the symphony as a medieval motet reimagined for the modern age.

Anton Webern: Symphony, Op. 21 – II. Variationen (Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; Herbert von Karajan, cond.)

Together, these ten works trace an astonishing metamorphosis of lush forests thinning into alpine clarity. The Second Viennese School never abandoned feeling, but rather found new ways to express it. Give these pieces your ear, and you may just find a new world to love.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

I don’t know if I will love them but at least I will know them better.

I don’t have the Wiener Philharmoniker Abonnement but I used to have one for the General Probe. Once the Director was Barenboim. There is always an intermission, and, while the public was going to their coffee (or a glass of Sekt), Barenboim turned round and said:

“As you know, we will after play the “Transfigured night”, I beg you to, please, come back”.

Bitte, bleiben.

Thank you!

No Verklaerte Nacht (Transfigured Night)?