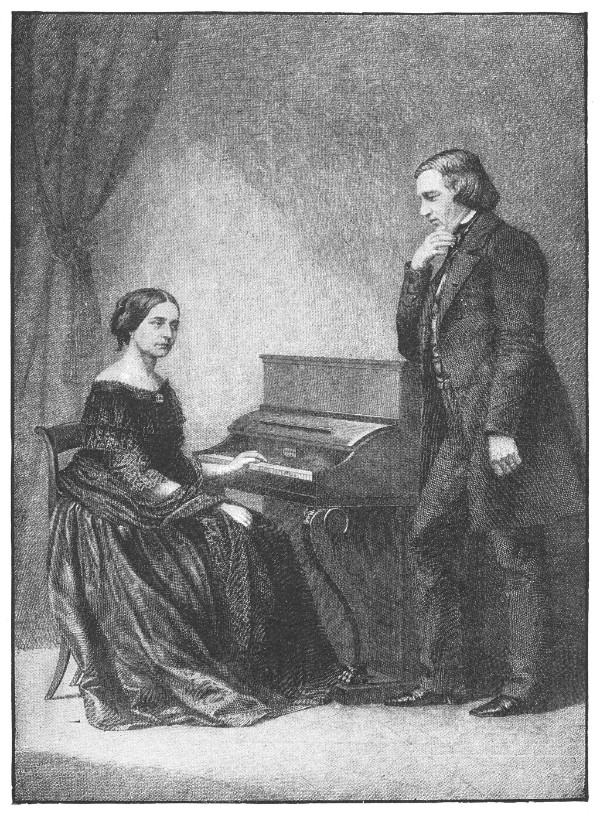

Clara and Robert Schumann, illustration from Famous Composers and their Works, 1906

Robert Schumann’s Fantasy in C Major, Op. 17, opens with a passionate declaration of what scholars and performers often call the “Clara theme,” a five-note descending scale. But what is this melody, and why does it matter? To understand it, its musical transformations and Schumann’s dialogue with Beethoven, is to understand the young Schumann himself.

Schumann Fantasy First Movement

This melody seems modest on its own, but it carries a remarkable emotional burden. It’s not only a cryptic musical anagram for Clara Wieck—Schumann’s forbidden beloved at the time, but also the spine of the entire Fantasy. The theme recurs obsessively, shape-shifting through every possible mood: yearning, ecstatic, desolate.

The theme wasn’t Schumann’s creation. Clara herself wrote it at the age of 13 in her dazzling Romance varié in C Major, Op. 3, which she dedicated to Schumann.

Hear the entire Romance varié played by Jozef de Beenhouwer

Clara Schumann: Romance variee in C Major, Op. 3 (Jozef de Beenhouwer, piano)

Three years later, in 1836, Clara reprised the theme in her Notturno (No. 2 of her Soirées musicales, Op. 6) using the same notes Robert would later adopt:

Hear the Notturno played by Konstanze Eickhorst

Clara Schumann: Soirées musicales, Op. 6 – II. Notturno (Konstanze Eickhorst, piano)

By then, their secret romance was in bloom—only to be abruptly blocked by Clara’s father, Friedrich Wieck, who was not only Schumann’s teacher and business partner but also, for a time, a father figure. In that turbulent year, Clara, a 16-year-old prodigy already fêted across Europe, was cut off from Robert by parental decree. Schumann, ten years her senior and not yet known as a composer, descended into what he would call his “year of agony.” They were forbidden even to write and could only communicate on occasion through an intermediary.

So Schumann did what any romantic genius might: he poured his feelings into music. In the Fantasy, he manipulated the Clara theme with infinite variety. The five-note diatonic descent becomes, at one point, a 15-note chromatic ascent buried in the bass. Elsewhere, the theme is inverted, fragmented, slowed to stillness, or launched heavenward in climax. These examples are from the first movement alone:

On the Fantasy’s title page, Schumann inscribed a line from the poet Friedrich Schlegel:

“Through all the tones in this colorful earthly dream,

a soft tone sounds for one who listens in secret.”

That listener was Clara, and Schumann composed for her ears to bridge the distance between them.

Schumann originally conceived the Fantasy as a standalone work titled Ruins, and in a letter to Clara, he later confessed that the first movement was “the most passionate thing I have ever written—a profound lament for you.” Coded throughout the movement are veiled quotations not just of Clara’s theme but also of a more distant musical idol: Beethoven.

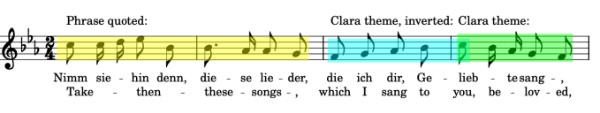

Alongside the Clara theme, Schumann embeds two phrases from Beethoven’s song cycle An die ferne Geliebte (To the Distant Beloved). The cycle’s central conceit—music as a bridge across enforced separation—echoed his plight. The phrase Schumann quotes most poignantly, the more important of the two, reflects his own act of sending music to a beloved he could not reach.

Following Beethoven’s example in works such as the Eroica or Diabelli Variations, Schumann first reveals fragments or variants of the theme, only stating it more clearly at the end of the movement. Here are several examples.

At the beginning of the piece, responding to the Clara theme:

At the end of the first movement, close to the original:

Liszt and Berlioz are usually credited with inventing thematic transformation, but both Schumann and Beethoven had already mastered the idea. They conceal and reveal their themes with such imagination that listeners may not even recognize how thoroughly a motif has been changed. In the Fantasy, even the rhythm and contour of the Beethoven quotation are slyly reshaped.

The second movement of the Fantasy, a march with dotted rhythms modeled on the scherzo from Beethoven’s Op. 101 Sonata in A Major, refracts the Clara theme through a bravura texture that hurtles toward a famously difficult coda. The third movement, elegiac and luminous, recalls the last movement of Beethoven’s Op. 111 Sonata in C Minor. Here, Schumann interweaves the Clara theme with retrograde and inverted forms of the Distant Beloved melody.

This article encapsulates analysis from a recording with video made last year of all three movements of the Schumann Fantasy. You can follow the entire piece with commentary here.

Schumann returned many times to the Clara theme in his early works, including the F Sharp Minor Sonata, Op. 11; the F Minor Sonata, Op. 14; and Kreisleriana, Op. 16. And there are many other quotations and cryptic allusions to Clara in his music as well.

Despite their obstacles, Robert and Clara married in 1840, on the eve of her 21st birthday. The Fantasy, completed four years earlier, remains a coded record of their separation, yearning, and unspoken communication. It’s not just a work of art. It’s a personal covenant between two great musicians.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter