As December assumes its full hegemony and all the familiar thoughts of Christmas come swirling in, a highlight of my days has been an activity that feels like a kind of daily Christmas present to myself: learning the cello.

Cello

I only have a rented model, an affordable student outfit in a warm amber colour – withholding a purchase and upgrade from myself has provided ample, yet superfluous, motivation to practice. In truth, there is a wonderful physicality to playing the cello, which means that even an hour-long session spent on scales is a joy, as well as a challenge involving real musicianship. Playing cello is a constant immersion, one’s senses directed towards the weight and movement of the bow, the rich resonance of the sound, the placement of the fingers. As a child, I was loath to perform my scales at the piano; as an adult, I sit and daydream about the prospect of learning a new scale or technique. My former viola teacher was never able to impress upon my impatient mind the importance of bowing long tones and open strings; as an adult, I do so at the cello with relish and a fervent attention to detail, recording my practice in a journal.

I have a private theory that every individual has a kind of “soul” instrument – an instrument whose physiology, sound, playing method, repertoire, and even appearance suits, at some deep level, that person. Some people are clearly singers, through and through. One can spot a flautist a mile away – and don’t get me started on the idiosyncrasies of brass players (they’re darling creatures, nonetheless). The exact metaphysical nature of this theory is unclear, even to me. A more solid conclusion, then, is that being an instrumentalist of any kind takes dedication, consistency, and care – and in the cello I have found an endeavour that feels truly like a labour of love, if a “labour” at all.

Kaija Saariaho: 7 Papillons – No. 5. — (Anssi Karttunen, cello)

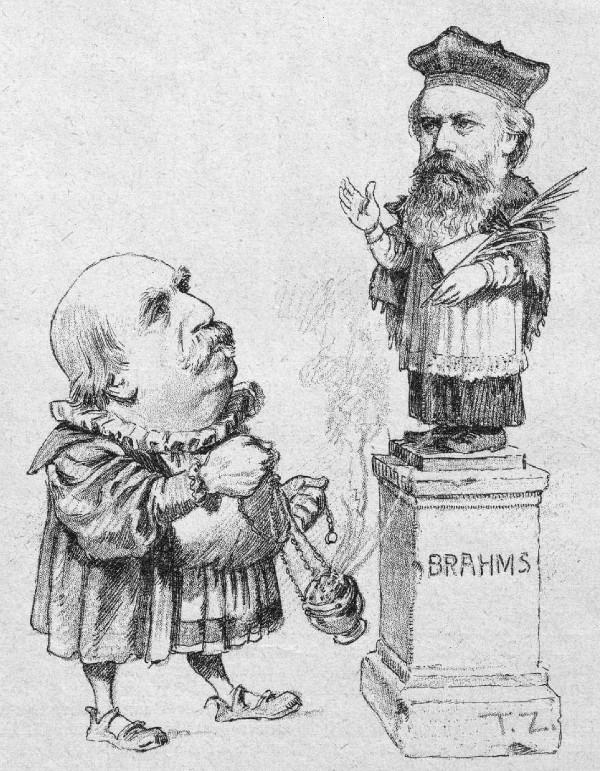

In light of this, it feels only fitting to be respectful and aware of history, and to present here a short history of this wonderful instrument.

If I may allude to the Christmas Carol, the cello has a strange name “to begin with.” The full name, violoncello, means “a small large viol,” as it contains suffixes of largeness, “-one,” and diminution, “-ello.” Indeed, until historically quite recently, there was no such thing as a violoncello – until the early 1700s, only the ancestor of the cello existed, the “bass violin.” Italian prints from 1609-1700 showcase about twenty names for the bass violin alone, suggesting that the make, function, and playing of this instrument were incredibly varied.

Monteverdi’s seminal opera Orfeo is one of the first surviving works to include a part for bass violin (in this case, “basso viola de braccio”). It was G.C. Arresti who seemed to coin the term “violoncello” in his Sonate op. 4, in 1665, and by 1700, this name was widespread.

The earliest depiction historians have been able to find of the bass violin is in Gaudenzio Ferrari’s The Concert of Angels, a ceiling painting in Saronno, Italy, from 1534-36. These pre-1700 instruments had strings made entirely of sheep gut, which meant that the discrepancy in thickness between upper and lower strings was great, afflicting the bass strings with the physical principle of inharmonicity – essentially, the overtones were muddy. Furthermore, thicker strings were very quiet, a fact which could only be improved with length makers stretched the strings as long as they possibly could without impeding the ability of the left hand to play in first position.

The Concert of Angels by Gaudenzio Ferrari

The invention of wirewound strings, the winding of thin wire around a core of gut string, was thus a serious breakthrough. With this, strings could be shorter and still create a resonant sound, and so the violone or bass violin could be made smaller and less cumbersome. Some bass violins were quite literally shaved and cut down, and evidence of this can be seen at the Musée des Instruments de Musique at Brussels Conservatory, where an unaltered and massive violone from 1702 sits alongside a drastically altered “cello” from 1670, which underwent operations to shift its f-holes to suit its new size.

Tuning systems for the bass violin and cello were also variable in these centuries, ranging from fifths built on F, Bb, and G on three, four, and five strings. Historians have analysed the tessitura of music by Monteverdi and concluded that his music favours a G-based tuning, whereas composer Giovanni Valenti calls for a Bb that no longer exists on the modern cello without scordatura (re-tuning). A treatise by J.F de la Fond from 1725 indicates that by this time, our modern C—G—D—A tuning had been adopted in England. Into the 18th century, the terms “violone” and “violoncello” co-existed.

By the early 1700s, renowned luthier Stradivari established a body size for the cello of 75-6cm (for full-size instruments) that persists to this day. Still, there was a way to go before cello playing occurred as it does today. Until 1750, players still often rested their instrument entirely on the floor, as we see in the painting The Cello Player by Gabriel Metsu, from 1660.

The Cello Player by Gabriel Metsu

At this stage, underhand bowing, as for viols, was still the norm. Towards 1700, it became more standard for players to lift the instrument off the floor and hold it with the calves, for the practical reason of allowing more complex fingering and bowing. Playing in thumb position, a now-established if not daunting technique for cellos, was not widely used until the mid-eighteenth century, at which time frets still appeared on some cellos.

The cello was clearly thought of as a kind of dual instrument and was constructed with variations for this reason. It existed both as a soloistic instrument and as a supporting bass instrument in ensemble contexts: for example, the Paris Conservatoire Méthode of 1805 refers to “violoncelle” for the former purpose, and “basse” for the latter accompaniment and orchestral instrument.

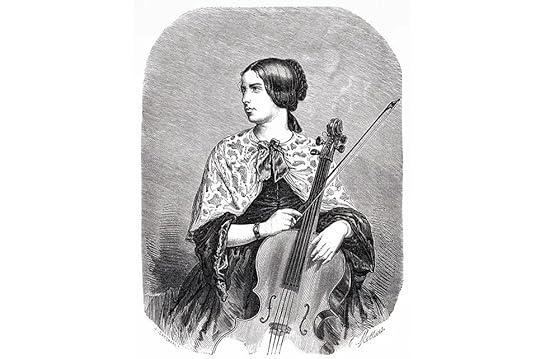

Italian cello-makers began to flourish in their trade from 1680 onwards, and cello-makers across Europe grew in number and stature throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. The earliest example of an “English” cello was made by William Baker in Oxford in 1672, and both convex and concave bows from this time can be found. Although players were finding comfortable adjustments for decades, such as placing the cello on a stool, the endpin was not recommended in a formal treatise until 1882, in Jules de Swert’s The Violoncello. An unforeseen advantage of the endpin was that it allowed women to play cello without violating rules of decorum – Lisa Cristiani is the only notable female cellist of whom we are aware from before the nineteenth century.

Lisa Cristiani

Vibrato is mentioned in treatises from the 18th and 19th centuries, sometimes called a “close shake” or a “tremolo.” Initially, cellists such as Dotzauer and his teacher Romberg gave precise parameters for when vibrato should occur, and advocated judicious use only, while cellists of the French school seemed to mostly refrain from using vibrato. It was these two German cellists of the Dresden school who also pioneered the frog bow-hold we use today. By the mid-eighteenth century, there were cellists across Europe whose instruments, playing techniques, and tuning systems we might find at least somewhat familiar in the 21st century.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter