In our last article about Maurice Ravel (Read “Maurice Ravel at the Turn of the Century”), we left off shortly after the resolution of the affaire Ravel, the controversy surrounding Ravel’s exclusion by the judges of the Prix de Rome from the further stages of the composition rounds. In a few years, Ravel was to suffer the blow of the death of his father. Before then, however, Ravel spent some years focused heavily on composing for piano.

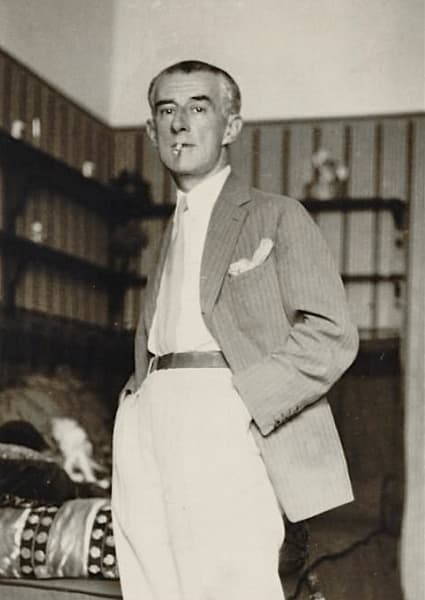

Maurice Ravel

Maurice Ravel: Sonatine (Brenda Lucas Ogdon, piano)

His Sonatine, composed between 1903-5, is a good expression of much of Ravel’s inclination towards classical aesthetics. In terms nonetheless contemporary to the times, Sonatine expresses allegiance with the ideals and forms of 18th-century classicism and the early French clavecinistes. Maurice Delage remarked on the Sonatine that the first movement was “reminiscent of some beautiful Roman melody,” the second movement a true minuet despite its truly modern modal harmonic inflections. Ravel biographer Burnett James posits that Sonatine was a fairly private work for Ravel, a concentration upon basic principles, technique, and a “confirmation of the underlying aesthetics of his art.”

On the whole, Ravel’s composition output is small, in terms of brute minutes of music, with respect to other composers of similar lifetime and stature. This slightly slower output may have been due to the exacting standards Ravel imposed upon himself, and the way he, as Burnett James puts it, “adhered to his ideals and his principles with remarkable tenacity,” composing only on his own terms.

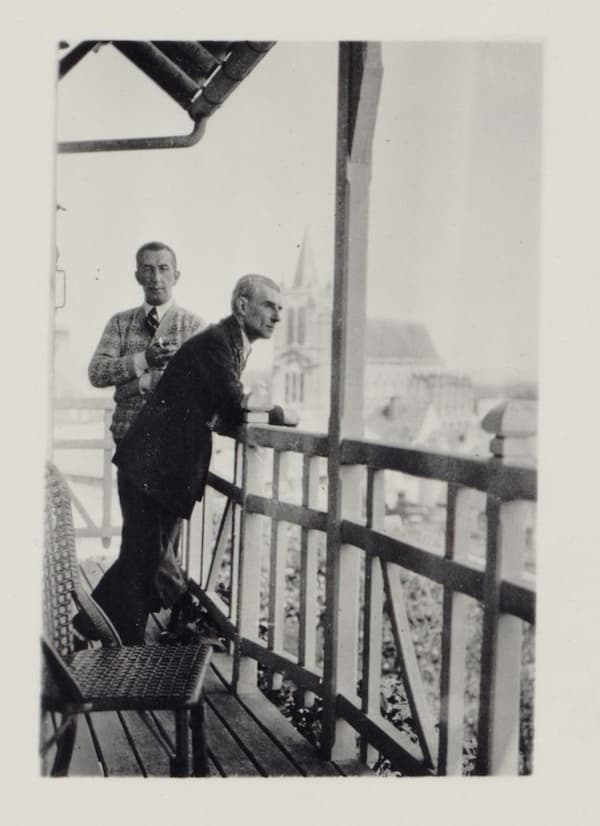

Maurice Ravel with Maurice Delage

The composition of Sonatine overlapped with that of one of Ravel’s most well-known and beloved works, Miroirs, for piano. Of Miroirs, Ravel himself wrote that the harmonic language would disconcert any who had grown accustomed to his former harmonic language. Each of the five movements was dedicated to a member of the Apaches, Ravel’s group of artistic and intellectual comrades. The set of works does much to reflect, as keenly and sharply as possible, like a mirror, a variety of images from the natural world: the overpowering strength of the sea, desolate birdsong in the forest at night, the fluttering of moths. In Alborada del gracioso, Ravel builds upon Domenico Scarlatti’s translation of guitar music into the realm of the keyboard; in La vallée des cloches, the sonic resonance of echoing bells and typically Ravellian melody close the set. The virtuosity, distinctiveness, and beauty of Miroirs further cemented Ravel’s standing, and Miroirs remains an essential part of the most masterful and challenging piano repertoire available in the 21st century.

Maurice Ravel: Miroirs (Brenda Lucas Ogdon, piano)

After this came two smaller commissions, the first a setting of traditional Greek songs from the island of Chios, requested by an Apaches member, M. D. Calvocoressi, required to illustrate a series of musicological lectures by Pierre Aubry. After the Cinq Mélodies populaires grecques, Ravel was commissioned by instrument makers at Maison Érard to create a work that highlighted the harp and could be used as a harp audition piece for the Conservatoire. The result was the chamber harp concerto, Introduction and Allegro for harp. Both this and the Greek folksongs were smaller in scope. Burnett James opines that, in general, Ravel was drawn more to the miniature, minute, and therefore perfectible, due to his predilection for aesthetic perfection, contrasted with the so-called “epic imperfection” of other composers’ larger-scale works. Counter-evidence for this idea can be found in Ravel’s music, such as the sprawling mechanical breakdown at the end of Boléro. Ravel’s own personality, enjoyment of mechanical toys, and Swiss heritage often interacted with appraisal of his music to create quite a reductive view of the man and his compositional output: the “[Ravel is the] most perfect of Swiss watchmakers” epithet by Stravinsky.

Maurice Ravel: Introduction et allegro (Skaila Kanga, harp; Academy of St. Martin in the Fields Chamber Ensemble, Ensemble)

Maurice Ravel

Ravel’s next project, a setting of Jules Renard’s poems about animals to music, the Histoires naturelles, caused a small kerfuffle and received some caustic reviews after its premiere. Despite instigating the occasional brouhaha, Ravel was nonetheless well-respected, and composer Ralph Vaughan Williams soon sought him out as a teacher. Vaughan Williams’ accounts of his studies with Ravel give us delightful insights into the latter’s views and character. For example, Ravel was apparently horrified to learn that the English composer had no access to a piano in his hotel, and exclaimed (in French), “without a piano, one cannot invent new harmonies!”

1907 seemed to constitute a critical year for Ravel in terms of exploring his fascination with Spain. In that year alone, Ravel composed in entirety, or began work on, three different “Spanish” compositions: the Vocalise-étude en forme de habanera, Rapsodie espagnole (versions for both orchestra and piano four hands), and the opera L’Heure espagnole. Ravel’s mother had grown up in Madrid, and sang him much Spanish music in his youth, both folk and theatre songs. Ravel wasn’t only interested in his mother’s own Northern Spanish roots; his imagination was captured by Southern Spain, the romance of Andalucía. With L’Heure espagnole, Ravel hoped to, in his own words, reanimate the principles of Italian opera buffa, using the “picturesque rhythms of Spanish music,” to create a “humoristic” opera that expressed irony through harmony and music itself, while showing off the inherent lilt and musicality of the French language through large portions of “ordinary declamation.” The opera tells the story of clockmaker Torquemada and his dallying wife Concepción, who live in eighteenth-century Toledo. In a farcical turn of events, Concepción’s lovers are hidden in clocks, carried up and down stairs, and ultimately snubbed for the obedient and strong clock-carrying Ramiro. Ultimately, Torquemada is less oblivious of his wife’s affairs than he initially seems, but savvily sees an opportunity for business when he catches her lovers ensconced – or stuck – in his clocks. The opera ends on a light-hearted quibble to the rhythms of the habanera.

Maurice Ravel: L’heure espagnole (Isabelle Druet, mezzo-soprano; Luca Lombardo, tenor; Marc Barrard, baritone; Nicolas Courjal, bass; Frédéric Antoun, tenor; Lyon National Orchestra; Leonard Slatkin, cond.)

Maurice Ravel

Ravel undertook the opera at a key juncture: it was written for his ailing father. The choice of mechanical clock-making was a fitting dedication for an engineer, and Ravel’s father had always wanted to see his son’s work put on in the theatre. Ravel set aside all other work and wrote uncharacteristically quickly. In a heartbreaking turn, the opera was not premiered at the Opéra-Comique until 1911, three years after Pierre-Joseph Ravel’s death, due to prevarications and hesitations on the part of director Albert Carré.

In the subsequent precious few years before the first world war, Ravel began work on two monumental compositions, one of which was the devilishly tricky Gaspard de la nuit…

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter