Sometimes listeners claim that music – and classical music in particular – is above politics.

Unfortunately for these people, history proves them wrong.

Many of the greatest composers in classical music history were deeply engaged with politics, and their political beliefs often found their way into their music.

Whether you’re a musician or a listener, these connections provide valuable insight into composers’ lives and careers.

Today, we’re looking at six great composers who supported political revolutions…and what happened to each of them.

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745–1799)

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges

Bologne was born in 1745, the son of a white plantation owner and his Creole slave. When he was a child, his father brought him to Paris, where he studied music and became a virtuoso violinist and composer.

Bologne spent his musical career associating with members of the French aristocracy. Yet he wasn’t a monarchist. In May 1790, he joined the French Revolution on the side of the revolutionaries.

He was appointed a captain and colonel of a thousand-member Black légion, known as the Légion Saint-Georges. They became famous for bravely fighting Austrian troops invading Lille.

Queen Marie Antoinette playing the harp

Initially, he was celebrated, but as the 1790s continued, politics shifted, and violence increased. Marie-Antoinette was executed in October 1793, signalling the increasing danger not only to the aristocracy but also to all those associated with it.

In the confusion of the Reign of Terror, and despite his military service, Bologne was sentenced to prison, where he remained for about a year between 1793 and 1794. He was lucky to escape with his life.

Bologne’s Violin Concerto in A, Op. 5, No. 2

In 1797, he helped establish an orchestra called Le Cercle de l’Harmonie, hoping to help rebuild French musical life in the years after the Revolution. Unfortunately, that dream was dashed in 1799, when he died of complications from a bladder infection.

It’s tempting to imagine what he might have done had he lived into the Napoleonic era.

Hector Berlioz (1803–1869)

Hector Berlioz, 1845

Hector Berlioz was born in rural France in December 1803.

At seventeen, he moved to Paris to study medicine. After he graduated from medical school, he enrolled at the Paris Conservatoire.

During those years of studies, he became involved with bohemian artistic circles in Paris.

After the Napoleonic era ended in 1814, a power vacuum opened in French politics, and the monarchy stepped into that vacuum when Louis XVIII, the younger brother of the executed Louis XVI, ascended to the throne in a restored (albeit constitutional) monarchy.

Louis XVIII was followed by another brother, 66-year-old Charles X, in 1824.

After elections in June 1830 resulted in a legislature that wouldn’t support their political goals, Charles X and his advisors suspended the constitution, freedom of the press, and freedom of assembly.

A 26-year-old Berlioz took to the streets during the three-day July Revolution of 1830, a struggle that became known as the Three Glorious Days, which ended with Charles’s abdication.

Afterwards, to celebrate, Berlioz wrote a large-scale arrangement of “La Marseillaise.” He was also commissioned to write a requiem – Grande Messe des morts – in memory of the victims of the revolution; that was premiered in 1837.

Berlioz’s Grande Messe des Morts

Frédéric Chopin (1810–1849)

Portrait of Frédéric Chopin by Eugène Delacroix, 1838

Frédéric Chopin was born in 1810 just outside of Warsaw; within the year, the family moved to the capital, where he grew up.

His friends and family in Warsaw, as well as his Polish identity more generally, were hugely important to him, even as a young man.

Being one of the most talented pianists in Warsaw, and therefore always in demand in aristocratic drawing rooms, he got to know the Russian leaders ruling over Poland at the time. But he resented the control they wielded, and the brutal ways in which they often wielded it.

Once he became a teenager, it became clear that he’d have to move to a bigger city than Warsaw to fulfill his professional potential.

Accordingly, in late 1830, he departed Poland to embark on a European tour. Weeks afterwards, Poles in Warsaw rose up against their Russian occupiers and oppressors in a conflict that became known as the November Uprising.

Chopin thought about returning to fight on behalf of the Polish revolutionaries, but he ultimately decided to continue on his tour instead.

The continuing political unrest meant that he never felt able to return to Warsaw safely.

His famous Revolutionary Étude is said to have been inspired by the bombardment of Warsaw during the uprising. He also wrote a number of polonaises, which are specifically Polish dances that celebrate Polish identity in the face of Russian oppression.

Chopin may not have physically fought in the uprising, but he spent the rest of his career advancing pro-Polish ideas in his music for generations to come.

Chopin’s Revolutionary Etude

Richard Wagner (1813–1883)

Richard Wagner at the piano

Richard Wagner moved to Dresden, Saxony, to work in 1842. After successful performances of his operas Rienzi and The Flying Dutchman, he was named Royal Saxon Court Conductor.

At the same time, despite his title, he was spending time with radicals and anarchists. Dresden was a hotspot for these kinds of liberal political beliefs.

Matters came to a boiling point in 1848, when people across the German states agitated for unification and a constitutional monarchy.

A National Assembly tried to secure legitimacy between 1848 and 1849, but faced an uphill battle for longevity.

Ultimately, the Assembly passed a constitution and offered the position of monarchy to the king of Prussia, Friedrich Wilhelm IV. However, he declined, and the Assembly eventually crumbled.

Meanwhile, Frederick Augustus II, King of Saxony, dissolved the local Saxon parliament. A more liberal parliament attempted to form in its place, but Prussian troops suppressed it. Predictably, the situation escalated, and residents of Dresden rebelled.

Eventually, the situation became so unstable that Saxon troops meant to keep the peace fired on the crowd. Chaos – and the May Uprising – ensued.

Wagner wrote articles encouraging his fellow citizens to revolt. He also served as a lookout and even made hand grenades. After the uprising failed, a warrant was issued for his arrest, and he fled to Paris.

When his opera Lohengrin was conducted by Franz Liszt in Weimar in 1850, Wagner was unable to attend because he was still in exile.

The entire experience cemented his reputation as a revolutionary: a reputation that would spill over into his music-making.

Wagner’s Prelude to Lohengrin

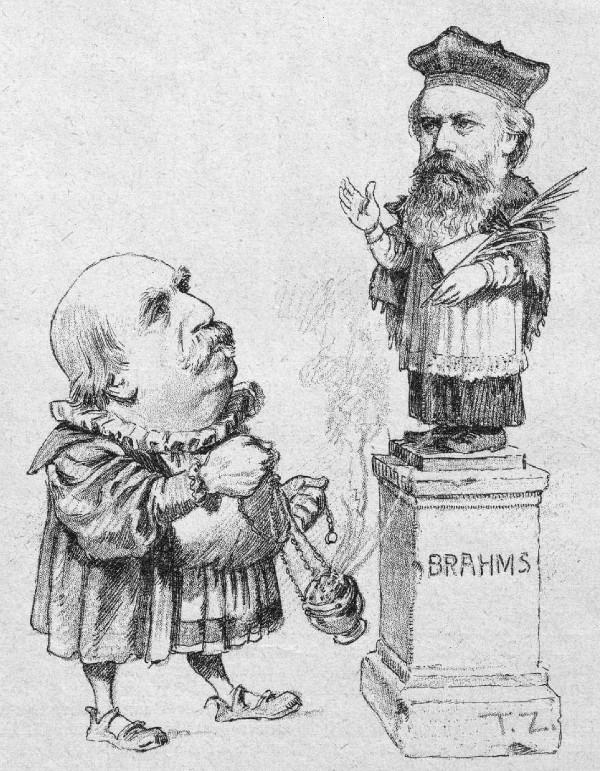

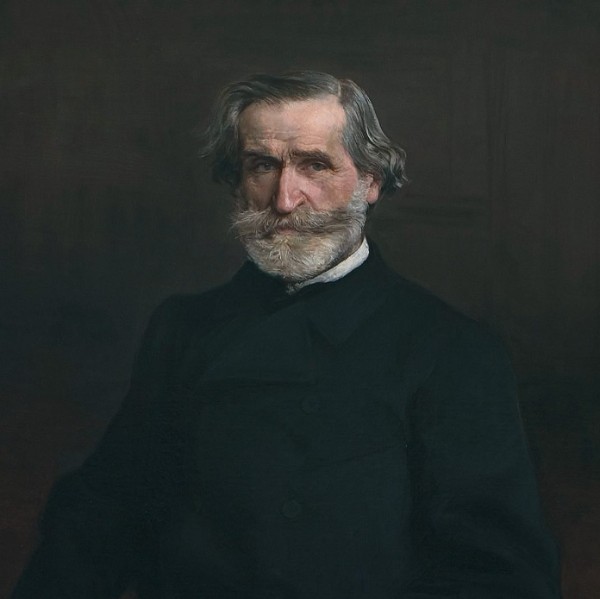

Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901)

Giovanni Boldini: Giuseppe Verdi, 1886 (Milan: Casa Verdi)

After the Napoleonic wars and the Congress of Vienna, Italy was controlled by the Empire of Austria.

But when revolutionary movements spread across Europe in the late 1840s, those movements spread to Italy, too.

When they did, Verdi was delighted. He wrote in a letter about the revolutionaries:

“Honor to these brave men! Honor to all Italy, which at this moment is really great! Be assured, her hour of liberation has come. It is the people who demand it, and there is no absolute power that can resist to the people…”

At the time, Verdi was the most celebrated composer in Italy. He supported not only the revolution against Austria but also Italian unification (a movement known as the Risorgimento), and he wasn’t afraid to lend his music to the cause.

In 1848, politician and activist Giuseppe Mazzini asked Verdi to write a patriotic hymn, and Verdi acquiesced.

The following year, in 1849, Verdi wrote an entire opera to commemorate the new government, La battaglia di Legnano. The opera was meant to be an allegory for the revolutionary movement.

The tenor’s final lines are “Whoever dies for the fatherland cannot be evil-minded”, while the work’s final chorus includes the lines “Italy rises again robed in glory!, Unconquered and a queen she shall be as once she was!”

Italian freedom and unification were finally achieved in 1861. Verdi’s operas became increasingly popular and began to be reinterpreted with revolutionary messaging…that had, perhaps, been unintentional originally.

In 1861, Verdi served briefly in the body that became the Italian parliament. Even today, he remains one of the most recognisably Italian composers.

Verdi’s La battaglia di Legnano

Bedřich Smetana (1824–1884)

Bedřich Smetana

In June 1848, the revolutionary fever sweeping across Europe flared in Prague, too. Citizens’ long-standing frustrations with Austrian rule boiled over, leading to demonstrations and attempts to establish a Slavic Congress.

However, Austria was not pleased at this push toward independence and self-determination. Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz, a field marshal in the Austrian army, increased military presence in Prague. The residents resisted, and violence broke out. Bedřich Smetana, 24, manned the barricades on the Charles Bridge in Prague.

The conflict quickly became deadly. Alfred’s wife was shot by a stray bullet while watching the conflict from the upper window of her hotel, and Alfred himself was nearly murdered, too.

A few days later, the revolutionaries were defeated, and many of them were punished for their roles in the uprising. Smetana was lucky to escape exile or execution.

In 1848, he wrote some patriotic music: two marches dedicated to the National Guard and the Students’ Legion of Prague, and a stirring choral piece “Song of Freedom” (“Píseň svobody”).

Smetana’s “Píseň svobody”

However, the Smetana works that we’re most familiar with today are the symphonic poems in Má vlast (My Fatherland), which embrace nationalism and include elements inspired by folk music and the Bohemian landscape.

Smetana’s Má vlast

Conclusion

These composers remind us that classical music has always been more than just entertainment: many works can also be interpreted as rallying cries, cultural statements, or both.

Whether through their direct actions on the barricades or through compositions that stirred nationalist pride, each of these six composers worked at the crossroads of music, politics, and revolution, and their compositions prove it.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter