Over the course of his career, bassist and conductor Serge Koussevitzky advocated for hundreds of new works, commissioned some of the most famous of them, helped launch a legendary summer music festival, taught a large percentage of the next generation of classical musicians, and led one of the greatest orchestras in the world for twenty-five years.

And yet, despite all that, not a lot of classical music lovers know much about his contributions to the art.

Today, we’re looking at the story of the life of Serge Koussevitzky, from how his career was made possible by his wealthy second wife to how he created the orchestral canon we know today.

Serge Koussevitzky’s Childhood and Student Days

Serge Koussevitzky as a student

Serge Koussevitzky was born in July 1874 to an impoverished family of musicians in Vyshny Volochyok, a small town halfway between St. Petersburg and Moscow.

His mother was a pianist (and died tragically when Serge was three), and his father was a klezmer musician who played both violin and bass. His siblings also played instruments.

As a child, he learned violin, viola, cello, trumpet, and piano.

At fourteen, he auditioned for the Moscow Conservatory but was rejected. Instead, he earned a scholarship to study at the Musico-Dramatic Institute of the Moscow Philharmonic Society. While there, he focused on studying the double bass.

A recording of Koussevitzky playing bass from 1929

Koussevitzky’s Early Career

At twenty, he joined the storied Bolshoi Theatre orchestra. Six years later, in 1901, he became principal bass.

He began giving concerts as a solo bassist. In 1903, he traveled to Berlin to give a recital there.

Koussevitzky also wrote a bass concerto, enlisting the help of composer Reinhold Glière to orchestrate it. (Interestingly, he never played it with an orchestra, and only performed it in a bass-and-piano arrangement.)

Koussevitzky’s Bass Concerto

A Consequential Affair and Divorce

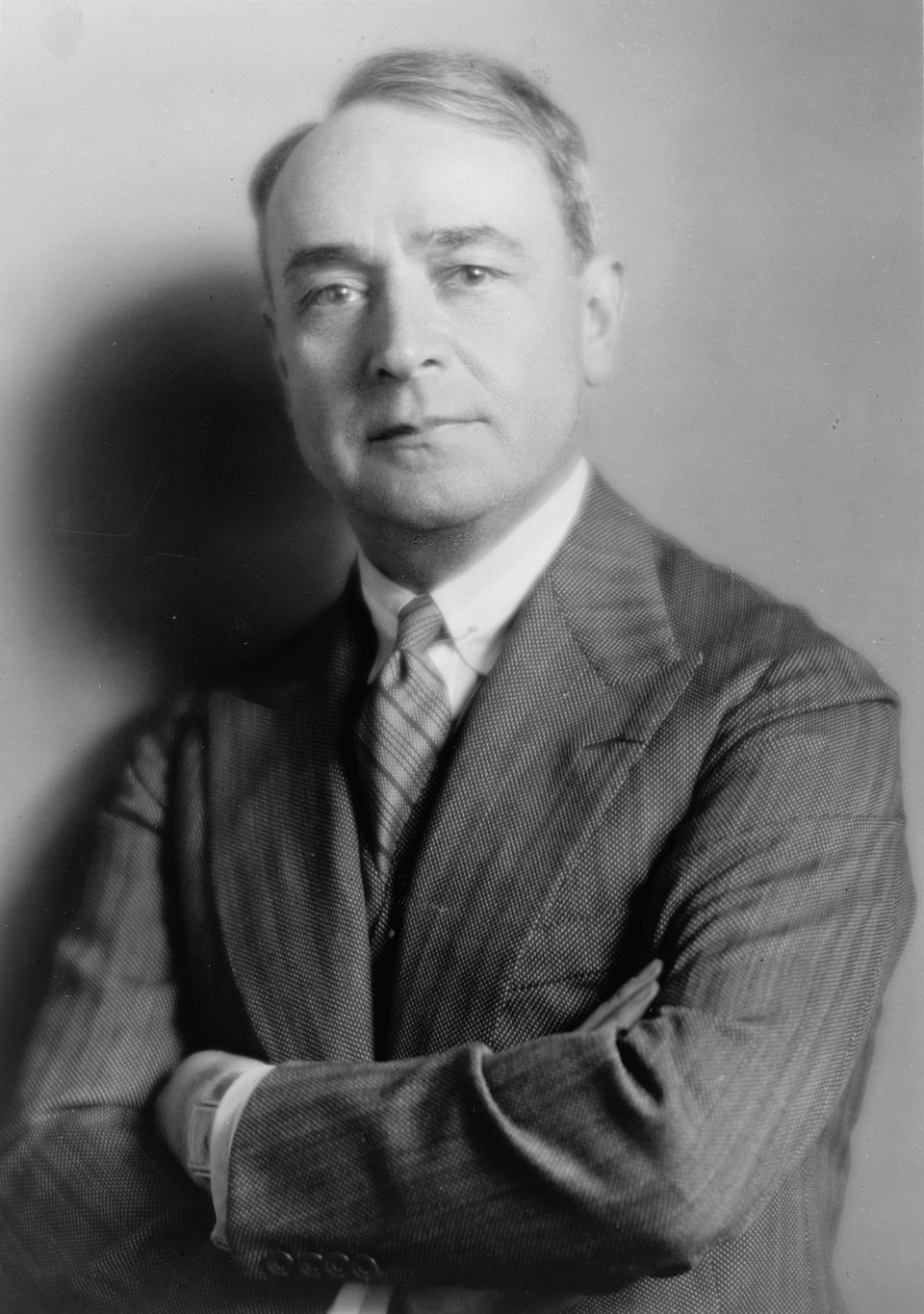

Serge Koussevitzky

Koussevitzky’s love life turned messy around this time…and the consequences would follow him for the rest of his career.

Around 1902, he married a dancer from the Bolshoi named Nadezhda Galat.

But according to a later newspaper article, during one of his early recitals, he looked out into the audience and locked eyes with a sculptor and tea heiress named Natalie Ushkova. They went on to fall in love.

The timeline is murky, but Koussevitzky ultimately decided he wanted to leave Nadezhda for Natalie. Nadezhda – understandably, given the social stigma – did not want to officially divorce, even after they separated. According to one article in The Atlantic, she actually horsewhipped one of Koussevitzky’s representatives when he came to discuss legalising the divorce. It took the intervention of Koussevitzky’s friends to convince her to agree.

Marrying Natalie (And Her Money)

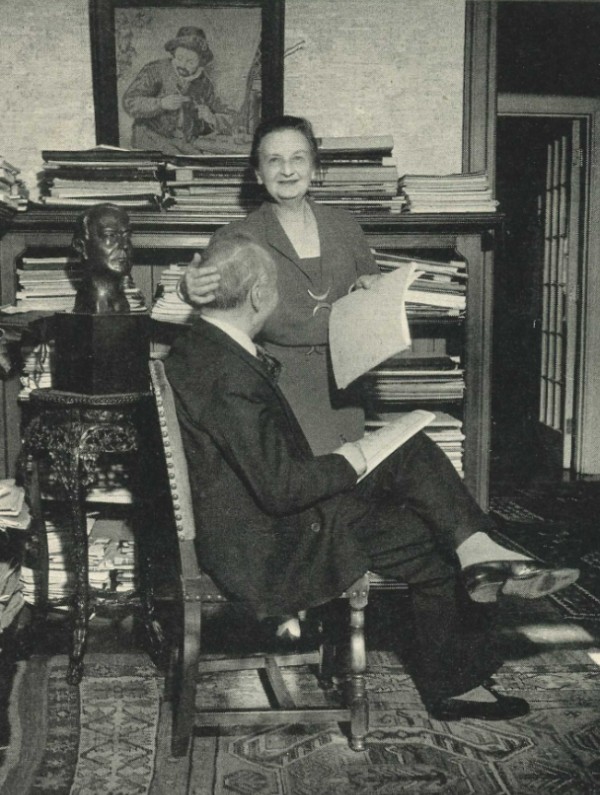

Serge Koussevitzky and his wife Natalie

Koussevitzky married Natalie the month after his divorce from Nadezhda became finalised. Natalie asked him what he wanted for a wedding present, and he said, “a symphony orchestra.”

Remarkably, on her own dime, she hired 85 musicians to use as guinea pigs for Koussevitzky’s conducting training.

Later they hired a boat and traveled with orchestra members up and down the Volga River between 1910 and 1914. Koussevitzky would give concerts in river towns and play modern works.

In 1909, she helped him to establish a publishing house, Russian Musical Editions. The company went on to publish works by Scriabin, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, and others, helping to introduce their works to international audiences.

The Koussevitzkys also spent time in Berlin early in their marriage. There, Serge used Natalie’s money to hire conductor Arthur Nikisch, the conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, to give him conducting lessons. According to legend, the Koussevitzkys paid off Nikisch’s gambling debts.

Landing a Conducting Job

In 1917, after the Russian Revolution began, Koussevitzky was named the conductor of the State Philharmonic Orchestra of Petrograd, which he led for three seasons.

But in 1920, he left the Soviet Union and moved to Paris. There, he founded a series of concerts known as the Concerts Koussevitzky, premiering new works by the most prominent composers of the day.

One of the most famous works he commissioned was Maurice Ravel’s orchestration of Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, giving that work new life and cementing Ravel as possibly the greatest orchestrator of the twentieth century.

Ravel’s Pictures at an Exhibition orchestration, premiered in 1922

In 1924, he and Natalie moved again, this time to take up the most important position of his career: music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO), the second-oldest orchestra in America.

His tenure was hugely formative for the orchestra, and he ended up staying there for a quarter century. Koussevitzky and the BSO made a number of renowned recordings together.

Natalie Koussevitzky

While there, his personal style was aggressive. Violinist Harry Ellis Dickson later remembered, “His orchestra, if they didn’t play well, it was a personal insult to him. He was not a gentleman. He was autocratic to the point of nausea, sometimes.”

Koussevitzky once told another player: “I’m the dictator. I say ‘do,’ and you do.”

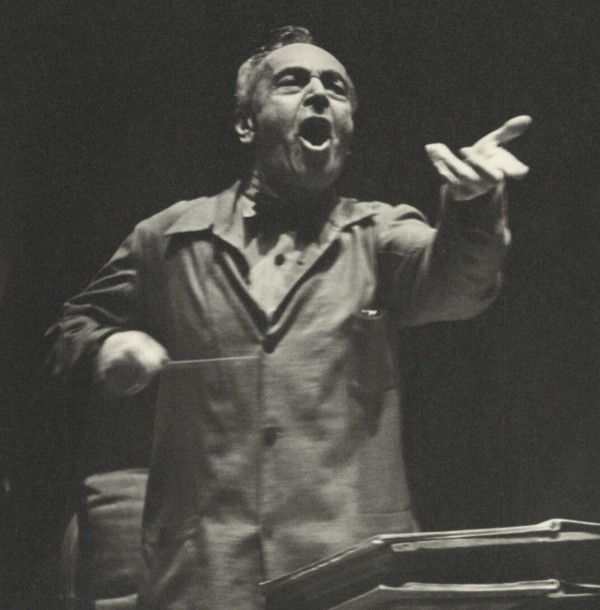

Koussevitzky conducting “The Seven Last Words of David” by Randall Thompson, 1960

It’s not a style that would be received warmly today by anyone, but in the mid-twentieth century, it was common.

Creating Tanglewood

Serge Koussevitzky

During Koussevitzky’s tenure in Boston, he teamed up with socialite and philanthropist Gertrude Robinson Smith to create the Berkshire Symphonic Festival, later renamed Tanglewood.

Smith had originally hired the New York Philharmonic to play at the festival, but two seasons in, in 1936, she hired Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony instead.

The following summer, a legendary concert interruption occurred: a thunderstorm cut short a performance of Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries.”

Smith took to the stage, took the microphone, and asked the audience: “Now do you see why we must have a permanent building for these concerts?” Then she took up a collection, and $30,000 was raised…in the depths of the Great Depression!

The structure that resulted – the Music Shed – was, in 1988, renamed the Koussevitzky Music Shed in recognition of all he had done for the festival during the 1930s and 1940s.

In 1940, Koussevitzky founded a music school for young musicians, which became the Tanglewood Music Centre. The list of alumni is a who’s-who of music: John Adams, Marin Alsop, Luciano Berio, Leonard Bernstein, John Harbison, Oliver Knussen, Lorin Maazel, Robert Spano, Michael Tilson Thomas, and countless others.

Koussevitzky Conducting Beethoven’s Egmont Overture at Tanglewood

Natalie’s Death and the Koussevitzky Foundation

Natalie died in January 1942. A devastated Koussevitzky decided to honor her memory by creating and funding the Koussevitzky Music Foundation.

In the words of composer and music historian Robert Greenberg, Koussevitzky “became one of the most important musicians in history, responsible for commissioning more masterworks than any other single musician before or since.”

A mini documentary from the BSO about Koussevitzky’s influence

At the Boston Symphony alone, Koussevitzky gave 146 world premieres, and that’s not even counting the works he helped to premiere back in Europe.

He or the Foundation commissioned Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra, Copland’s third symphony, Britten’s opera Peter Grimes, Bernstein’s Serenade, and countless more.

The Koussevitzky Foundation still helps support composers to this day. As of 2024, the Foundation has distributed 448 grants: a remarkable, and remarkably tangible, legacy.

The Koussevitzky/Boston Symphony world premiere recording of Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra, 1944

Final Years and Legacy

Koussevitzky remarried in 1947 to Natalie’s niece Olga Maumova. He retired from the Boston Symphony in 1949 and died in 1951. He was buried next to Natalie in Lenox, Massachusetts.

Despite his importance to classical music history, it has been seventy-five years since someone wrote a full-length English-language biography of Koussevitzky. Maybe it’s time for orchestra lovers to learn more about him, his staggering legacy, and how he shaped the canon we still know today.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter