Over the last few centuries, the history of the piano has been shaped by rivalries between pianists: sometimes friendly, sometimes fierce.

Today, we’re looking at some of the most famous rivalries in piano history, dating from the 1780s to the 1980s.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart v. Muzio Clementi

Mozart vs Clementi

One of the earliest and most famous piano duels took place on Christmas Eve, 1781.

That night, Emperor Joseph II invited Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) and the Italian pianist-composer Muzio Clementi (1752–1832) to compete in a piano duel before the Viennese court.

Amazingly, Joseph II told his guests about the duel…but not the musicians!

Despite being caught off-guard, both Clementi and Mozart dazzled listeners. Clementi played a self-written showpiece and a virtuosic toccata, while Mozart performed variations on “Ah, vous dirai-je, Maman” (known today as the Twinkle Variations).

Mozart’s Twinkle Variations

They also played works by composer Giovanni Paisiello, then improvised on a Paisiello theme.

Ultimately, the emperor declared the showdown a draw.

Mozart, however, was more critical, writing to his father a couple of weeks later that Clementi was “a mere mechanicus” with “not a kreutzer’s worth of taste or feeling.”

Clara Wieck Schumann v. Marie Pleyel

Clara Schumann

In the 1830s, two of Europe’s most celebrated female pianists – Clara Wieck (later Clara Schumann, 1819–1896) and Marie Pleyel (1811–1875) – became rivals…of a sort.

Clara’s playing emphasised fidelity to the score and interpretive seriousness. Franz Liszt gave her the chaste nickname of “priestess.”

Marie Pleyel

Meanwhile, Marie was renowned for her glittering technique and brilliant style. (She was also infamous for her romantic misadventures… She was engaged to Hector Berlioz; she married the much older piano manufacturer Camille Pleyel, then cheated on him; and it appears that she once hooked up with Liszt in Chopin’s apartment!)

Clara Wieck Schumann’s Romance, dating from 1839

In 1840, Clara wrote in her diary:

“Everything that I read about [Marie Pleyel] is an ever clearer proof that she is above me; and if this be so, I can hardly fail to be completely downcast.”

She believed that society would only accept one great woman pianist. However, happily, both ended up having impressive international careers.

When she finally met Marie in 1851, she wrote another entry in her diary:

“I was very pleased to meet her, since I had heard so much about her, and I was actually very surprised by her great amiability, which seemed so perfectly natural.”

Frédéric Chopin v. Friedrich Kalkbrenner

Frédéric Chopin, 1829

When Frédéric Chopin (1810–1849) moved from Poland to Paris in 1831, he began rubbing elbows with Friedrich Kalkbrenner (1785–1849), the city’s reigning piano virtuoso.

Friedrich Kalkbrenner

Kalkbrenner was a dazzling technician, influential teacher, and successful composer. His fame and reputation were such that by the time he met Chopin, he was a wealthy man.

Kalkbrenner’s 5 Variations brilliantes on a mazurka by Chopin, Op. 120

After Chopin’s Paris debut, Kalkbrenner offered to take him as a pupil, under the condition that Chopin stay with him for at least three years.

Chopin thought about it, but ultimately declined, writing to his best friend back home in Warsaw:

“He offered to take me as a pupil for three years, and to make a great artist of me. I replied that I knew very well what were my deficiencies; but I did not wish to imitate him, and that three years were too much for me.”

Chopin’s decision was a signal that he was not going to be subservient to Kalkbrenner and that he was going to compete with him in Paris for fame and patronage.

In the end, the rivalry was less a personal feud and more a brief power struggle between two very different pianists from two very different generations.

Kalkbrenner would eventually be almost totally forgotten, while Chopin would become one of the most famous pianists and composers in music history.

Franz Liszt v. Sigismond Thalberg

Franz Liszt and Sigismond Thalberg

The most famous piano duel of the Romantic era took place in Paris in 1837 between Franz Liszt (1811–1886) and Sigismond Thalberg (1812–1871).

Both men were idolised for their virtuosity: Liszt for his showmanship and demonic energy, Thalberg for his “three-hand effect,” which creates the illusion of multiple voices playing at once.

One critic wrote in 1836:

Moscheles, Kalkbrenner, Chopin, Liszt and Herz are and will always be for me great artists, but Thalberg is the creator of a new art which I do not know how to compare to anything that existed before him.

When Thalberg heard Liszt for the first time in 1837, he found himself dumbstruck by what he witnessed.

Meanwhile, that same year, Liszt wrote an article for publication criticising Thalberg’s musicianship:

Posing M. Thalberg as representative of a new school! Apparently, the school of arpeggios and thumb-melodies? Who would admit that this was a school, and even a new school? Arpeggios and thumbs-melodies have been played before M. Thalberg, and they will be played after M. Thalberg again.

Their rivalry was officially on!

A film adaptation of their duel from the movie “Szerelmi álmok – Liszt”

In 1837, Princess Cristina Belgiojoso hosted a duel between the two giants at her salon as part of a fundraiser for Italian refugees.

After both pianists performed, the princess, unwilling to displease either pianist at her charity event, tactfully declared:

“Thalberg is the first pianist in the world; Liszt is unique.”

Happily, any major personal differences they had soon disappeared. While his and Liszt’s touring itineraries crossed paths in Vienna in 1838, they met up to eat a couple of meals together.

When Thalberg visited the court of Saxony and received honours there, he told the king, “Wait until you have heard Liszt!”

Vladimir Horowitz v. Arthur Rubinstein

Horowitz at Carnegie Hall

The twentieth century brought new piano rivalries for audiences to enjoy.

One of the most memorable was the rivalry between Vladimir Horowitz (1903–1989) and Arthur Rubinstein (1887–1982).

Arthur Rubinstein

The mercurial Horowitz dazzled with steely speed and hyper-controlled dramatics, while Rubinstein was admired for his pearl-like tone and nobility of onstage presence.

A documentary about how Horowitz and Rubinstein were “complimentary opposites”

Though they respected each other, given their shared Eastern European background, of course, audiences inevitably compared them.

Horowitz, for his part, had a similar love-hate relationship with Rubinstein’s playing. He once told his friend David Dubal, “You know, Rubinstein was an ugly man, but he had a noble face. And, by the way, a big technique!”

As for Rubinstein, he believed that Horowitz was the better pianist…but that he himself was the better musician.

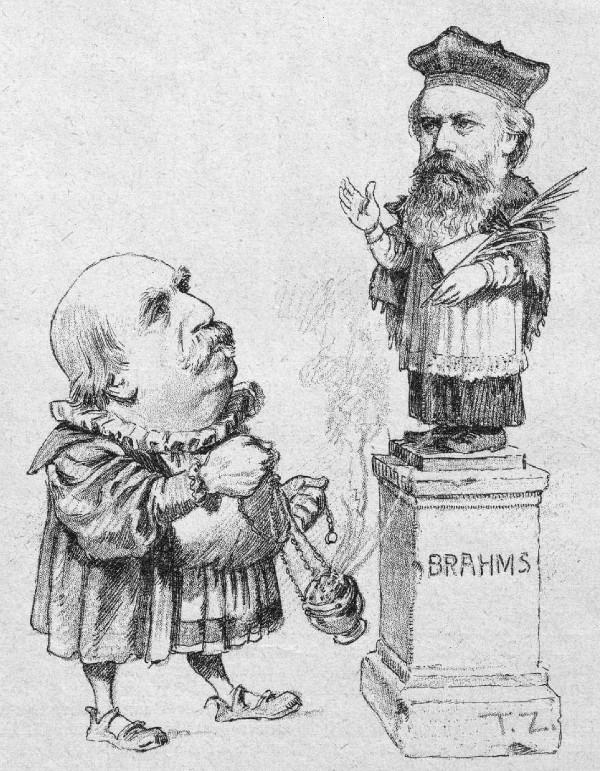

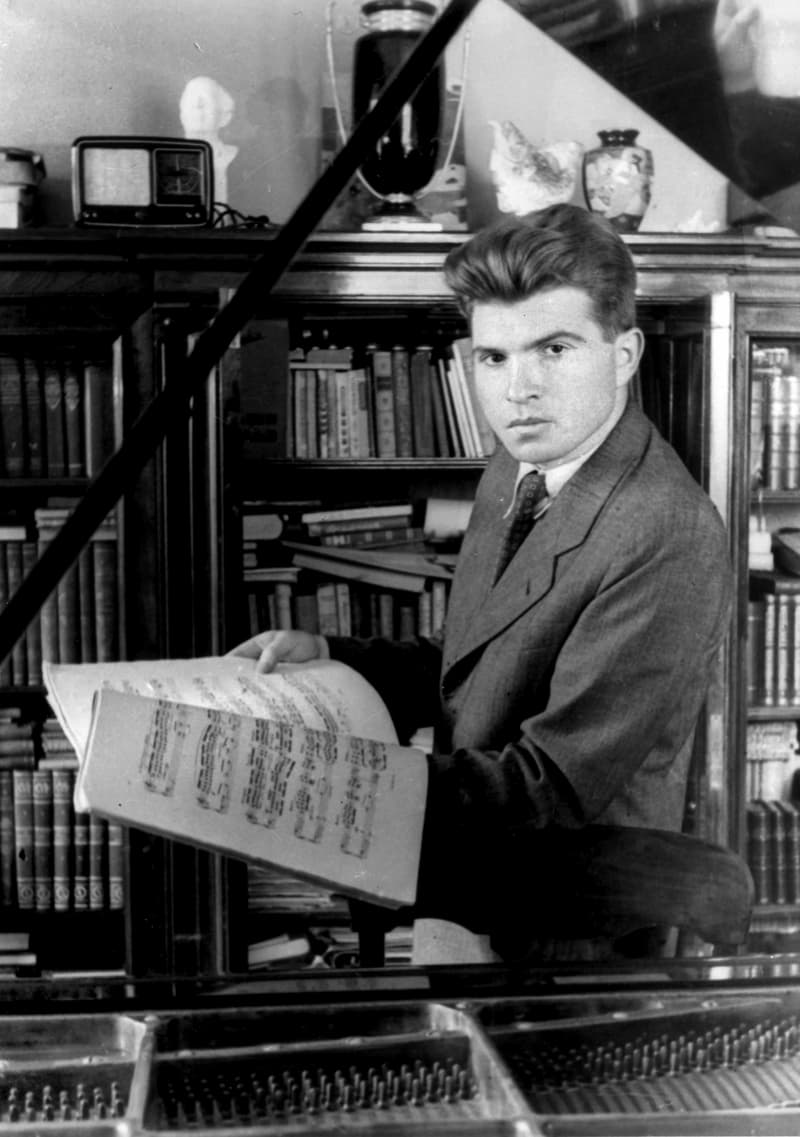

Sviatoslav Richter v. Emil Gilels

Sviatoslav Richter

Here’s a second set of contemporaneous piano giants from the Soviet Union: Sviatoslav Richter (1915–1997) and Emil Gilels (1916–1985).

Both were brought up in the rich Russian piano tradition, but their temperaments differed: Richter was more introspective and experimental, while Gilels was more extroverted (in fact, his brutal playing earned him the nickname The Butcher).

A documentary excerpt comparing Gilels and Richter

Despite their differences, their paths often crossed. Prokofiev’s seventh piano sonata was premiered by Richter, while his eighth was premiered by Gilels.

Emil Gilels, 1940

They were also both on the Tchaikovsky Competition jury that gave the American pianist Van Cliburn his jaw-dropping 1958 victory.

Despite their differences in personality, they both respected each other. While touring America as an artistic ambassador for the Soviet Union, Gilels would say, “Wait until you hear Richter!” It was a throwback line to Thalberg talking about Liszt.

Conclusion

Piano rivalries aren’t just about who can play faster, louder, or even better.

They also draw out contrasts between great artists, cementing their strengths, weaknesses, and overall identity in the public consciousness.

Therefore, they can provide unexpected insights into the great pianists’ playing, as well as audiences’ perceptions of great pianists’ playing.

In the end, these rivalries enriched the art form, spurring pianists to new heights of accomplishment and leaving behind some personal history as fascinating as that of the music they played.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter