On a cold January day in 1751, 17 January to be exact, Venice lost in Tomaso Giovanni Albinoni one of its most intriguing musical sons.

Far from being a dull footnote in Baroque history, Albinoni’s life and legacy paint a vivid picture of a composer who refused convention, embraced independence, and left behind music that still sparks controversy, admiration, and heartfelt debate centuries later.

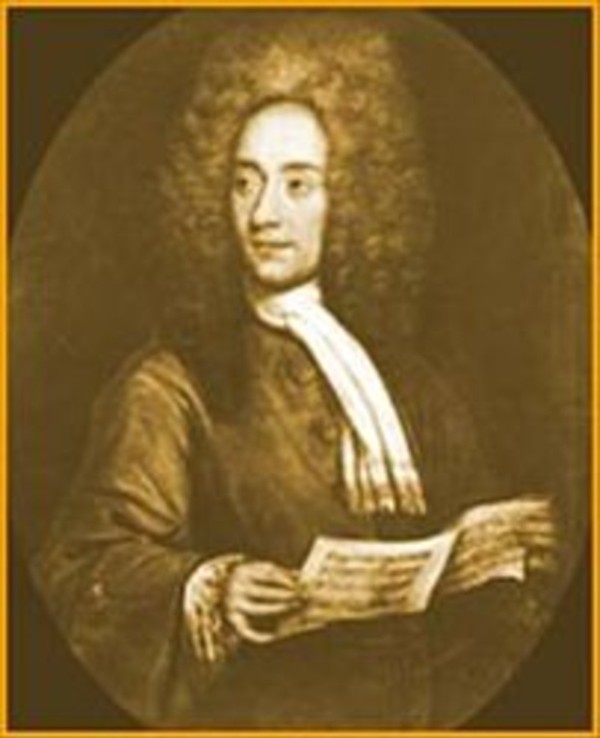

Tomaso Albinoni

To commemorate Tomaso Albinoni‘s passing, let’s not only remember a Baroque composer but celebrate a musical spirit whose work continues to speak through oboe concertos, lost operas, reconstructive controversies, and the soft echo of a melody many thought was his own.

Tomaso Albinoni: “Adagio”

Privilege Meets Melody

Venice in the late 17th century was a city of water, colour, carnival masks, squawking gondoliers, and a marketplace that hummed like a well-tuned harpsichord. It was here, on 8 June 1671, that Tomaso Albinoni was born into comfort and privilege.

His father was Antonio Albinoni, a wealthy paper merchant. This fact shaped Tomaso’s whole life as he didn’t need a patron’s salary, and he never took a court or church position.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Albinoni composed for love, not for livelihood.

This is one of the reasons music historians sometimes call him an “amateur.” From childhood, he studied violin and singing, but he also enjoyed wide access to Venetian culture, courts, and learned circles. The city was a bubbling soup of theatrical innovation and cosmopolitan tastes, and Albinoni fits right in.

Tomaso Giovanni Albinoni: Zenobia: Overture (Simon Desbruslais, trumpet; Charivari Agréable, Ensemble; Kah-Ming Ng, cond.)

Vanished Opera, Lasting Fame

Tomaso Albinoni

In 1694, at the age of 23, Albinoni premiered his first opera, Zenobia, regina de’ Palmireni, in Venice’s famed Teatro Santi Giovanni e Paolo. The opera was popular, earning him local acclaim and a ticket into Italy’s thriving operatic scene.

Over the next two decades, he wrote more than 50 operas, with Albinoni actually claiming to have written 81. These productions toured in the Italian cities of Venice, Genoa, Bologna, Mantua, Naples, and others. These operas captivated audiences with drama, passion, and a flair that was distinctly Venetian.

Yet, ironically, most of these operas are now lost, basically victims of time, neglect, and the ravages of war. With them, we lost much of Albinoni’s voice as a dramatist. What survives, in large part, is his instrumental music instead.

Master of Oboe

Today, Albinoni is best remembered for his instrumental music, primarily concertos, sonatas, trio sonatas, and especially concertos for oboe. He was one of the first Italian composers to elevate the oboe as a solo instrument.

He published nine major collections of instrumental works, spanning violin, strings, oboe, and chamber music, all marked by a lyrical melodic style and inventive textures that harmonised the elegance of Venice with Baroque drama.

Even Johann Sebastian Bach admired him. Bach didn’t just nod politely, but he based several keyboard fugues on Albinoni’s themes and used his bass lines as teaching tools for students.

Tomaso Albinoni: Oboe Concerto in D minor, Op. 9, No. 2

The Adagio That Never Was

No discussion of Albinoni can ignore the piece most people associate with his name, the “Adagio in G Minor.” This piece is so hauntingly beautiful that it seems almost to embody the melancholy of winter itself. But here’s the twist. Albinoni didn’t actually write the famous Adagio as we know it.

In 1958, more than two centuries after his death, an Italian musicologist named Remo Giazotto claimed to have found a tiny fragment of Albinoni’s music in the ruins of the Dresden State Library, which was destroyed during World War II.

Giazotto took that sliver, perhaps a six-bar melody and a bass line and built the now legendary “Adagio” around it. Whether that fragment truly existed or was a creative stroke bordering on musical myth remains debated among scholars, musicians, and classical music Reddit threads alike.

Yet the piece has taken on a life of its own, appearing in films, funerals, commercials, and heartfelt playlists the world over. It has become, for many, the sound of gentle sorrow, slow reflection, and soulful beauty, all attributed to Albinoni.

Attrib. Albinoni: “Adagio”

Freedom over Fame

Today, relatively little is known about Albinoni’s personal habits, his inner life, or his daily quirks. Such details have been blurred by time and the loss of records. We do know, however, that he married the opera singer Margherita Rimondi in 1705.

The couple had as many as six children, but their names disappeared into historical fogs.

He never sought a formal post, never curated heavenly choirs under an ecclesiastical boss, nor served courtly life under a demanding aristocrat.

Instead, he composed independently, supported by family means, which was a rare privilege that shaped his career and perhaps his artistic freedom.

Albinoni faded into obscurity in his final years, composing less and living out his later life in Venice, the city of his birth and eventual death.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Fugue on a Theme by Albinoni, BWV 946

From Life to Legacy

On 17 January 1751, Tomaso Albinoni died in Venice at age 79. That’s a ripe old age in a period when life wasn’t taken for granted. According to parish records, the cause was diabetes mellitus, a condition that, before modern medicine, would have slowly worn down his health.

He was buried in his beloved Venice, a fitting final stop for a man whose music had graced Venice’s canals and concert halls.

Yet his legacy didn’t end there. Everything from his oboe concertos to his operatic imprints and even the mythic “Adagio” continues to animate the hearts of musicians and listeners alike.

Tomaso Giovanni Albinoni: Violin Sonata in D Minor, So 35 (Federico Guglielmo, violin; L’ Arte dell’Arco, Ensemble)

The Voice of Venice

Albinoni’s musical style is characterised by rich ornamentation, emotional depth, and dramatic contrasts. Venice itself was a cultural crossroads, where music, art, and social life intertwined with religious rituals, carnivals, and the ebb and flow of the Adriatic tides.

Albinoni’s music reflects this world. It is warm, expressive, often lyrical, but rooted in structure. In his concertos and sonatas, listeners hear not merely harmonic frameworks but sometimes playful and sometimes solemn melodic conversations.

His style influenced peers and successors alike, helping pave the way for later developments in orchestral and chamber music.

Tomaso Giovanni Albinoni: Sinfonia in F Major (Enrico Di Felice, flute; Antonio Ligios, guitar; Paola Erdas, harpsichord; Ensemble L’Apotheose, Ensemble)

Echoes of Albinoni

Engraving of Italian composers Tomaso Albinoni, Domenico Gizzi (Egizio) and Giuseppe Colla by Pietro Bettelini, after a drawing by Luigi Scotti

If you’ve ever drifted into a quiet moment with a Baroque playlist or wondered whose music gets used in movie soundtracks, reflective moments, or classical radio hours, you’ve encountered Albinoni’s influence.

He reminds us that music is always evolving, sometimes in strange ways, like a piece becoming famous centuries after its composer’s death, written by someone else entirely.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter