In today’s world, a viral hit spreads in hours. In the late seventeenth century, it could take years or even decades for music to travel. And yet some works achieved a level of popularity that crossed borders, languages, and social classes.

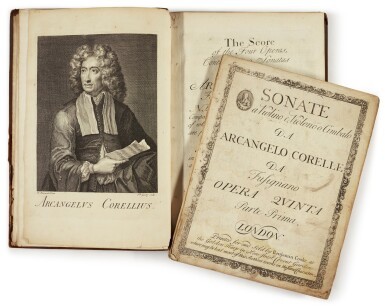

Among them, few rival the astonishing success of Arcangelo Corelli’s Violin Sonatas Op. 5. Published in Rome in 1700, these twelve sonatas became the best-selling instrumental music of the Baroque era, copied, pirated, arranged, and reprinted across Europe for more than half a century.

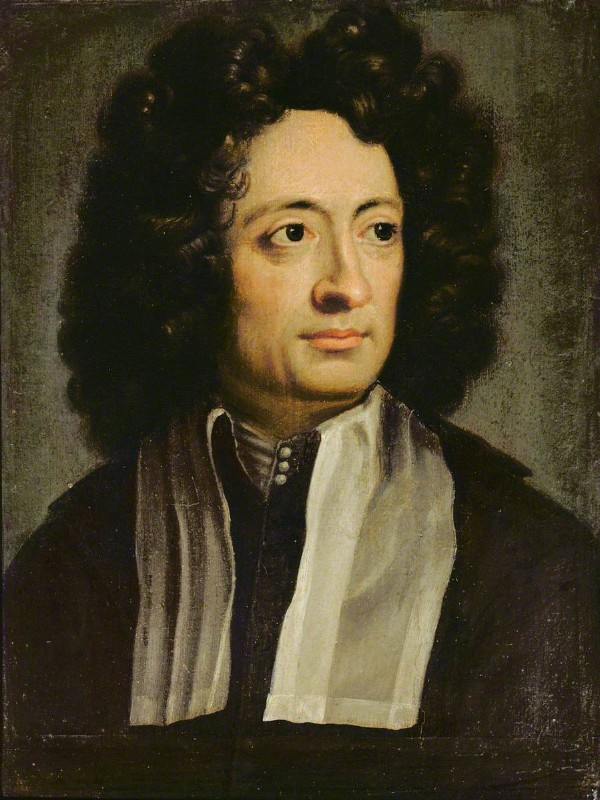

Arcangelo Corelli

To commemorate Corelli’s passing on 8 January 1713, we explore this collection of instrumental music that everyone wanted to own, play, and hear, whether they were professionals in royal courts or enthusiastic amateurs at home.

Arcangelo Corelli: Violin Sonata in D Major, Op. 5, No. 1

New Marketplace

By 1700, Europe’s musical world was changing rapidly. Music was no longer written solely for churches or courts. The rise of music printing had created a new kind of audience. Private buyers like merchants, lawyers, doctors, and well-educated aristocrats were purchasing instruments and printed music to perform at home.

This new market needed music that was refined but not forbiddingly difficult, expressive but not eccentric.

Corelli understood this world perfectly. Unlike many composers of his time, he was cautious about publishing. He released only a handful of collections during his lifetime, but each was carefully polished.

When Opus 5 appeared, it immediately stood out. Not because it was flashy, but because it was clear, balanced, and beautifully proportioned. The music felt complete and authoritative, as if it had already been tested and perfected.

Printers quickly realised they had a treasure on their hands. Demand spread far beyond Rome. Within a few years, editions appeared in Amsterdam, London, Paris, and Antwerp, often without Corelli’s permission.

Music piracy was rampant, but it was also a sign of success. Printers pirated only what they knew would sell.

Arcangelo Corelli: Violin Sonata in D minor, Op. 5, No. 7

The Perfect Product

Collection of the early editions of Corelli’s Op. 5

One reason the Opus 5 sold so well lies in its careful design. The collection includes both “sonate da chiesa” (church sonatas) and “sonate da camera” (chamber sonatas), appealing to different tastes and settings.

Some movements are lyrical and reflective, others dance-like and lively. The famous final sonata, built on the La Folia theme, offered something irresistible, namely a simple tune transformed through increasingly inventive variations.

Just as importantly, the violin writing struck a careful balance. The music is demanding enough to reward skilled players, but it avoids extreme virtuosity. For amateurs, this was ideal.

Playing Corelli signalled good taste and education, not reckless showmanship. For professionals, the sonatas provided a model of style, phrasing, and expression that could be adapted to almost any situation.

This adaptability was crucial. The pieces of Op. 5 could be performed in a salon, a court chamber, or a private home. It could be played with a rich continuo group or with a single keyboard. Flexibility, after all, was a commercial advantage.

Arcangelo Corelli: Violin Sonata in E minor, Op. 5, No. 8 (Viola arrangement)

A Name That Sold Itself

We only need to look at the sheer number of reprints to tell the story of the Op. 5 success. By the middle of the eighteenth century, the sonatas had appeared in nearly fifty editions. Some were luxurious, aimed at wealthy collectors.

Others were cheaper and more practical, intended for students and amateurs. Printers often advertised Corelli’s name prominently, sometimes even exaggerating his involvement in later editions.

His reputation became a selling point in itself. Owning Corelli was a mark of seriousness, a sign that one belonged to Europe’s shared musical culture.

This culture crossed national boundaries. Italian music was fashionable, but Corelli’s style was unusually universal.

French musicians admired its clarity. English audiences embraced its elegance. German composers studied its structure. Opus 5 became something like a common musical language, understood all the way from Naples to Hamburg.

Arcangelo Corelli: Violin Sonata in C Major, Op. 5, No. 3 (Remy Baudet, violin; Jaap ter Linden, cello; Mike Fentross, guitar; Mike Fentross, theorbo; Pieter-Jan Belder, harpsichord)

Piracy as Compliment

Arcangelo Corelli

In the modern world, piracy is often seen as theft. In Corelli’s time, it was also a form of tribute. Unauthorised editions of Opus 5 appeared almost immediately after the Roman publication.

Some printers altered the music, added ornaments, or included their own prefaces. Others issued simplified versions to reach a wider market.

Far from damaging Corelli’s reputation, this uncontrolled spread increased it. The music circulated faster than any official network could manage. Each new edition reinforced the idea that Opus 5 was essential repertory.

Ironically, piracy also helped standardise Corelli’s influence. Even when the notes were altered, the overall style remained recognisable. Composers and performers absorbed these traits, often without realising how deeply they were shaped by him.

Arcangelo Corelli: Recorder Sonata No. 10 in F Major, Op. 5, No. 10 (Maria Giovanna Fiorentino, recorder; members Fiori Musicali, Ensemble)

Arrangements

Arcangelo Corelli

One of the clearest signs of the set’s popularity is the astonishing number of arrangements it inspired. The sonatas were rewritten for flute, recorder, oboe, and even for solo keyboard.

In England, where domestic keyboard playing was especially popular, arrangements for harpsichord allowed players to enjoy Corelli without a violin at all.

These adaptations extended the life of the music. A violin sonata might appeal to a limited audience, but a keyboard arrangement could reach almost anyone with a harpsichord or spinet.

Corelli’s Opus 5 escaped its original form and became part of everyday musical life. The La Folia variations were particularly adaptable.

They appeared in countless versions, sometimes barely resembling the original. Each arrangement acted like a new “share” in modern terms, sending Corelli’s music into fresh contexts and communities.

Arcangelo Corelli: La Folia, Op. 5, No. 12 (arr. Geminiani)

Between Pedagogy and Pleasure

The Corelli Opus 5 was truly exceptional as it had the ability to speak to both professionals and amateurs. Court musicians admired its structural perfection, and teachers used it as a model of good style.

Students practised it to learn phrasing and tone. Meanwhile, amateurs enjoyed playing music that sounded noble and expressive without demanding extreme technical feats.

This wide appeal explains why Corelli’s Opus 5 remained popular long after Corelli’s death in 1713. Even as musical tastes shifted toward the galant style and later toward Classicism, Corelli’s sonatas retained their authority.

They were seen as timeless, not tied to a passing fashion, and for violinists, it was a foundation. For music lovers, it was a reliable source of pleasure. Few instrumental works of the time achieved such longevity.

Arcangelo Corelli: Violin Sonata in B-Flat Major, Op. 5, No. 2 (Ensemble Aurora, Ensemble)

Bestseller Changed the Rules

The success of Corelli’s Opus 5 had lasting consequences. It showed publishers that instrumental music could be profitable on a large scale.

It encouraged composers to think about international audiences. And it demonstrated that clarity, balance, and expressive depth could be more marketable than sheer novelty.

Later composers built on this lesson. Handel, Geminiani, and even Bach absorbed Corelli’s influence, sometimes directly through the Opus 5 set. The idea that instrumental music could circulate widely in print became a cornerstone of European musical culture.

In this sense, Opus 5 was more than a successful publication. It helped define what a musical “work” could be. It was something stable enough to be printed and collected, yet flexible enough to be adapted and reinterpreted endlessly.

Arcangelo Corelli: Violin Sonata in G minor, Op. 5, No. 5

Viral before the Internet

If we strip away the historical distance, Corelli’s Op. 5 behaves remarkably like a modern viral phenomenon. It appeared at the right moment, filled a real need, spread through both official and unofficial channels, and invited endless reinterpretation.

But unlike many viral hits, Opus 5 endured. Its popularity was not built on shock or novelty, but on qualities that listeners and players continued to value.

More than three centuries later, these sonatas are still played, studied, and loved. That enduring appeal is perhaps the clearest proof of why Corelli’s Opus 5 was the bestseller of the Baroque age.

And that success was no historical accident, but a triumph of musical intelligence, cultural timing, and quiet genius.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter