Francis Poulenc, the enfant terrible of French music, never did anything halfway. When he composed Les mamelles de Tirésias (The Breasts of Tiresias) in 1947, he didn’t merely write an opera.

Instead he wrote a cheeky, whirlwind rebellion against societal norms, gender expectations, and, against operatic seriousness itself. The opera is based on Guillaume Apollinaire’s surrealist play of the same name, and it keeps the audience perpetually off balance.

Francis Poulenc

Here, gender is not fixed, social conventions are mocked with gleeful abandon, and breasts, well, they literally take centre stage. To celebrate Poulenc’s birthday on 7 January 1899 let’s sip this operatic cocktail blending champagne, wit, and surrealist confetti.

Francis Poulenc: Les mamelles de Tirésias (Excerpt)

Surrealism before Breakfast

Welcome to Zanzibar. Not the exotic island of postcards, but a place where logic has called in sick, and surrealism is running the show. This is the world of The Breasts of Tiresias, where nothing behaves as expected, specifically not human anatomy.

Our story begins with Thérèse, a woman who wakes up one morning and decides she’s had quite enough of being a woman. Cooking? Child-rearing? Domestic expectations? Absolutely not.

In a fit of operatic rebellion, she declares herself a man, and thus Thérèse becomes Tirésias. In one of opera’s most famous stage directions, her breasts detach themselves and float off like liberated balloons. Sigmund Freud would have had a field day.

With her transformation complete, Tirésias marches off to conquer the world of politics, journalism, and public life. Meanwhile, her bewildered husband is left behind, staring at the empty kitchen and realising that gender roles, like reality itself, are highly negotiable.

Francis Poulenc: Les mamelles de Tirésias (Teaser)

Motherhood by Lunchtime

Poulenc’s Les mamelles de Tirésias (The Breasts of Tiresias)

If Thérèse can change sex before breakfast, perhaps he can become a mother by lunchtime. And so he does. Determined not to be outdone, the Husband decides to repopulate the nation entirely on his own. In a single afternoon, he produces thousands of children.

Not through biology, mind you, but through pure surrealist determination and a great deal of paperwork. Babies appear like confetti, piling up faster than the orchestra can count them. The message is clear. If society insists on absurd expectations, the only reasonable response is even greater absurdity.

As the opera races toward its conclusion, chaos reigns supreme. Gender is fluid, reproduction is industrialised, and logic has been thoroughly dismantled. Yet beneath the farce lies a strangely earnest plea.

The final chorus, rather shockingly, turns toward the audience and calls for love, responsibility, and, after two World Wars, more children. What begins as a dadaist prank, complete with flying body parts and impossible fertility, ends as a heartfelt humanist statement.

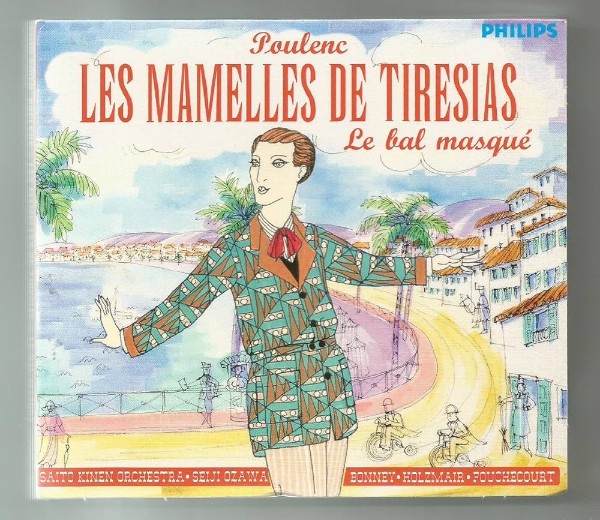

Francis Poulenc: Les mamelles de Tiresias, FP 125 – Act I: Ah! chere liberte (Graham Clark, tenor; Mark Oswald, baritone; Barbara Bonney, soprano; Jean-Paul Fouchécourt, tenor; Tokyo Opera Singers; Saito Kinen Orchestra; Seiji Ozawa, cond.)

Cabaret Meets Grand Opera

Poulenc’s Les mamelles de Tirésias (The Breasts of Tiresias)

Poulenc’s music mirrors this topsy-turvy story with sparkling wit, jazzy rhythms, and sly pastiches of French cabaret. The score flits between the high-brow and low-brow with nimble elegance.

One moment you’re hearing a lush, operatic aria that could belong in any grand opera house, and the next you’re toe-tapping along to a tune that feels like it belongs in a Parisian nightclub.

Jeremy Sams writes that Poulenc ransacked French music history from 1870 to 1920. “There are numerous echoes of Offenbach, Messager, Chabrier’s L’étoile and Ravel’s L’heure espagnole, not to mention numerous comic operas by lesser-known composers such as Maurice Yvain and Henri Christiné, which were all the rage in 1916.”

Francis Poulenc: Les mamelles de Tirésias, “Non, Monsieur, mon mari”

Anatomy Under Review

Humour in The Breasts of Tiresias is never just slapstick or decorative whimsy. It is clever social commentary and satire with teeth. Beneath the opera’s tumbling gags, surreal transformations, and verbal fireworks lies a sharp critique of social convention.

Poulenc, following Apollinaire’s mischievous lead, uses comedy as a solvent, dissolving the supposedly “natural” hierarchies of gender and power and revealing them as theatrical constructs.

Thérèse’s outrageous metamorphosis does more than provoke astonishment. It destabilises the assumption that identity, authority, and destiny are anchored in anatomy. Long before gender theory entered mainstream discourse, the opera gleefully exposes the absurdity of defining social roles through biological determinism.

Yet, the opera never preaches, Poulenc does not lecture, and Apollinaire does not scold. Instead, they trust the intelligence of the audience, allowing laughter to open the door to thought. In The Breasts of Tiresias, laughter becomes not an escape from reality, but a way of seeing it more clearly.

Francis Poulenc: Les mamelles de Tiresias, FP 125 – Act II: Ah ! c’est fou (Jean-Paul Fouchécourt, tenor; Tokyo Opera Singers; Saito Kinen Orchestra; Seiji Ozawa, cond.)

Controlled Anarchy

Poulenc’s Les mamelles de Tirésias (The Breasts of Tiresias)

Then there is the surrealism, which functions as far more than decorative absurdity. The opera’s fantastical elements include flying furniture, breast-shaped balloons marching off like unruly recruits, and a heroine who quite literally changes sex before our eyes.

Yet, these are not simply visual jokes designed to provoke astonishment. They form a theatrical and musical metaphor for the elasticity of human experience. Reality in this world is not denied, but it is gleefully stretched.

Poulenc responds to Apollinaire’s surrealist provocation with music that refuses to sit still. His orchestration delights in instability and surprise. Woodwinds flutter and chatter as if commenting on the action with raised eyebrows.

Brass fanfares swell with mock heroism, parodying the grand gestures of opera seria, and strings swoop, skid, and rebound like cartoon acrobats. The effect is not chaos, but controlled anarchy.

Francis Poulenc: Les mamelles de Tiresias, FP 125 – Act II: Mon cher papa (Anatoly Gridenko, tenor; Jean-Paul Fouchécourt, tenor; Saito Kinen Orchestra; Seiji Ozawa, cond.)

Absurdity with a Heart

Francis Poulenc

Because of its absurdity, The Breasts of Tiresias carries a surprisingly poignant message about liberation and self-expression. Thérèse’s audacious act of self-transformation becomes a metaphor for defying societal constraints.

And Poulenc’s language, with its charm, wit, and occasional biting irony, amplifies this theme. Just goes to show that some things are best served with a side order of humour.

For modern audiences, the opera feels remarkably fresh. Its satire of gender roles, capitalist absurdities, and social pretensions is still relevant. It’s clear that opera need not always be solemn, tragic, or stuffed with heavy-handed morality.

Francis Poulenc: Les mamelles de Tiresias, FP 125 – Act II: Il faut s’aimer ou je succombe (Barbara Bonney, soprano; Jean-Paul Fouchécourt, tenor; Akemi Sakamoto, mezzo-soprano; Wolfgang Holzmair, baritone; Tokyo Opera Singers; Saito Kinen Orchestra; Seiji Ozawa, cond.)

Dizzy with Meaning

The Breasts of Tiresias is heady, dizzying, and impossible to ignore. It asks us to laugh at ourselves, question our assumptions, and revel in the absurdity of life.

Familiar settings and realistic behaviour are turned on their heads, reshuffled and juxtaposed, producing effects and events which, though recognisable, become variously hilarious, impossible and disturbing.

Let’s not forget, however, that the opera was revised during wartime and that its message of needing to repopulate and re-establish France was a very real concern.

Francis Poulenc/Denis Duval: Les mamelles de Tirésias (Excerpt)

Poulenc Unleashed

Despite an abundance of comic music, the composer’s restraint and taste win the day. There are obvious influences, but it could only have been written by Poulenc.

The composer viewed it as one of his most “authentic” works, alongside Figure humaine and his Stabat mater. He reportedly thought of it very highly as it fully revealed his “complex musical personality.”

And, if you ever find yourself at an opera house and hear a flute fanfare announcing a sex-changing revolution, don’t panic. You’re not hallucinating but experiencing Poulenc at his most mischievous, most brilliant, and most delightfully irreverent.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter