Climate change is the defining crisis of the 21st century. It has reshaped how we understand the world around us and our place within it.

While the sciences describe the mechanisms of warming and the economics examine mitigation strategies, the arts offer a unique terrain for emotional engagement and interpretation.

Classical music, often perceived as timeless or insulated from current affairs, is increasingly confronting climate change not as a backdrop but as a subject worthy of artistic inquiry. To be sure, its relationship to climate change is asking hard questions.

What role should classical music play in a world undergoing ecological collapse? Can centuries‑old traditions contribute meaningfully to a future threatened by rising temperatures, biodiversity loss, and resource scarcity?

Through evocative soundscapes, innovative structures, and collaborations that bridge art and science, contemporary composers are asking listeners to feel climate change rather than merely understand it intellectually.

As we face the challenges in 2026 and beyond, let’s explore how composers and performers within the classical tradition have begun to treat climate change as something more than context. New works directly engage climate issues, and reinterpretations of musical narratives are expanding the repertoire’s ecological consciousness.

Steven Mackey: Urban Ocean

Immersive Soundscape

In recent decades, a growing number of composers have embraced climate change not as peripheral inspiration but as a central artistic subject. These works do more than evoke nature. They immerse us in sonic environments shaped by environmental data, field recordings, and visceral metaphors for ecological phenomena.

Perhaps the most celebrated example of this trend is John Luther Adams’ Become Ocean. Written in 2013 and awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Music and a Grammy Award, Become Ocean is a sprawling orchestral meditation that models the swelling and retreating energies of the sea.

Become Ocean

The piece creates an immersive, wave-like sound world that suggests rising sea levels and the ocean’s vast, shifting forces. While Adams does not describe the work as explicit activism, its inspiration from oceanic processes and the existential spectre of a world increasingly dominated by water aligns it directly with climate concerns.

John Luther Adams: Become Ocean

Fragile Harmonies

Another prominent climate-centred work comes from the Italian composer Ludovico Einaudi. Elegy for the Arctic was commissioned by Greenpeace, and Einaudi performed it on a floating platform amidst melting Arctic ice in Svalbard.

Behind Einaudi’s piano, vast glaciers cracked and drifted apart, a silent choreography that framed the music with unsettling clarity. The setting itself became part of the composition, collapsing the distance between art and environment.

Ludovico Einaudi © Decca/Ray Tarantino

The work speaks in a restrained, almost fragile language. Its gently unfolding harmonies, repetitive figures, and long-breathed phrases create a sense of stillness tinged with grief. There is no grand climax, no heroic struggle, only a quiet insistence.

Einaudi does not attempt to sonically represent catastrophe. Instead, he allows the listener to sit with a slow, ongoing, and irreversible loss. He translates the abstract language of climate data into a deeply human experience of mourning, attention, and care.

Ludovico Einaudi: Elegy for the Arctic

Sonic Testimony

Composers are increasingly turning to field recordings and non-traditional sound sources to confront listeners with environmental realities. In Liquid Interface, American composer Mason Bates incorporates recordings of glaciers calving in Antarctica.

Vast sheets of ice are fracturing, collapsing, and plunging into the sea with a thunderous and eerily hollow sound. These are not symbolic gestures but literal traces of a world in transformation. Bates captures moments of irreversible change.

Liquid Interface

Bates embeds these elemental sounds of water within a symphonic framework. Essentially, he collapses the boundary between concert hall and climate-impacted landscape.

Bates’ work thus becomes an act of sonic testimony, allowing endangered landscapes to speak within one of Western culture’s most venerable artistic spaces. Liquid Interface exemplifies how contemporary classical music can transform environmental data and distant catastrophe into immediate and embodied listening.

Mason Bates: Liquid Interface, “Glaciers Calving”

Singing for the Vanishing

Beyond large orchestral works, some of the most poignant climate-responsive compositions engage with specific, intimate facets of ecological loss. Mass for the Endangered by Sarah Kirkland Snider confronts the crisis of biodiversity not through spectacle or alarm, but through ritual.

Cast in a choral form historically reserved for human salvation, remembrance, and transcendence, the work quietly but radically expands the circle of concern to include nonhuman life, as species vanish without ceremony or witnesses.

Sarah Kirkland Snider

Snider’s music moves between lament and fragile affirmation. Prayer becomes not a plea for divine intervention, but a recognition of human agency and responsibility. The voices do not sing about endangered species, they actually sing for them.

By placing environmental loss within a sacred musical structure, Snider asks listeners to experience extinction not as a statistic but as a moral wound. The work reframes biodiversity loss as a spiritual crisis as much as an ecological one.

Sarah Kirkland Snider: Mass for the Endangered

Climate into Sound

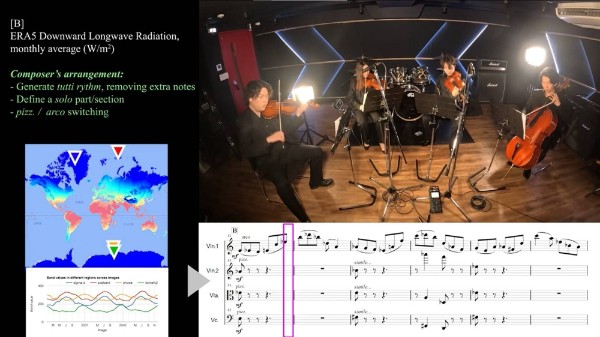

Some composers take an even more data-driven and conceptually radical approach. They represent climate change, but translate it directly into sound. Japanese musician and geoscientist Hiroto Nagai occupies a rare position at the intersection of scientific analysis and artistic creation.

In his string quartet Polar Energy Budget, Nagai sounds climate data from the Arctic and Antarctic, converting measurements of planetary energy balance into musical pitches, rhythms, and formal trajectories. It’s not an illustrative score atop scientific knowledge, but a work where data itself becomes the compositional engine.

Polar Energy Budget

The effect is quietly unsettling. As the quartet unfolds, patterns repeat, stretch, and destabilise, mirroring the gradual yet relentless shifts occurring at the Earth’s poles. The music does not dramatise catastrophe, but instead, it reveals imbalance through accumulation and drift.

Polar Energy Budget asks listeners to confront the emotional weight of scientific precision. It asks to feel the anxiety, fragility, and inevitability embedded in numbers that are often encountered only as graphs or headlines.

Hiroto Nagai: String Quartet No. 1, “Polar Energy Budget”

Reframing Nature

The growing presence of climate themes in contemporary music points to a wider change within classical music itself. Composers are expanding the kinds of stories this tradition tells, making room for ecological concerns that were largely absent in the past.

For centuries, classical music has celebrated nature in descriptive ways, but it rarely asked deeper questions about why nature changes or what happens when natural balance is disturbed.

Well-known works such as Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony and Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons are perfect examples. These pieces reflect the optimism and orderliness of the Enlightenment and Romantic eras, when nature was often seen as stable, generous, and ultimately reliable.

Listening to these works today can feel very different. When heard through an ecological lens, they no longer sound like timeless celebrations of nature, but gentle reminders of how fragile natural cycles have become.

Max Richter: Vivaldi Recomposed, “The Four Seasons”

Prophetic Soundscapes

Older works can take on new life when we listen to them through an ecological lens. Einojuhani Rautavaara’s Cantus Arcticus, often described as a “concerto for birds and orchestra,” gently invites the natural world into the concert hall.

Alongside the orchestra, we hear recorded birdsong from the Arctic, real sounds from a fragile landscape and not an imagined imitation.

Einojuhani Rautavaara

The birds do not decorate the music; they share space with it, reminding us that human culture and the natural world are deeply connected.

When Rautavaara composed the piece in the early 1970s, climate change was not yet a common subject in music or public debate. And yet, heard today, Cantus Arcticus feels almost prophetic. What once sounded like a peaceful meeting between nature and orchestra can now feel like an act of listening to something already at risk of disappearing.

Einojuhani Rautavaara: Cantus Arcticus

Timeless Elements and Urgent Messages

Some composers respond to climate change by weaving ecological ideas into familiar musical traditions, creating works that feel both ancient and urgently modern. In Rachel Portman’s Tipping Points, spoken poetry and orchestral music come together to explore the four classical elements.

Earth, water, air, and fire, those basic building blocks of the world, become powerful metaphors for environmental thresholds we are now dangerously close to crossing.

Rachel Portman

As the music unfolds, each element is given its own emotional character. Water can sound nourishing and life-giving, but also overwhelming. Air feels light and fragile, yet increasingly unstable. Fire carries warmth and energy, but also destruction. Earth suggests grounding and continuity, while quietly revealing signs of strain.

Portman draws on ancient ways of understanding the world while speaking directly to contemporary scientific warnings about climate change. The result is music that feels both timeless and immediate, reminding us that today’s environmental crisis is not just a technical problem, but a deeply human one.

As climate change reshapes our world, classical music stands at a turning point. It can remain a beautiful escape, or it can use its power to awaken awareness, inspire reflection, and encourage action. Engaging with the environment isn’t just about greener concerts; it is about rethinking how music connects us to the planet and to each other.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Thank you for this timely and interesting article. I am particularly grateful for learning about Hiroto Nagai -a new name to me. I’ve been a student of Sonofication (the process/art of transposing data into sound) for over a decade and the field of Acoustic Ecology continues to be a a fascinating and urgent topic. Alas, with the cuts to many environmental and liberal arts programs, this research and fields of study are increasingly as endangered at their subject, but the works of multi-disciplinary researcher/musicians like Prof. Nagai keeps the topic clearly in focus.

Music has no meaning beyond its notes. Trying to pretend that it reflects a composer’s feelings is absurd. If you wan to expresss your feelings, write it down or talk to someone. Music is its own meaning and language. It isn’t verbal. Let’s get rid of this nonsense; it’s long overdue.