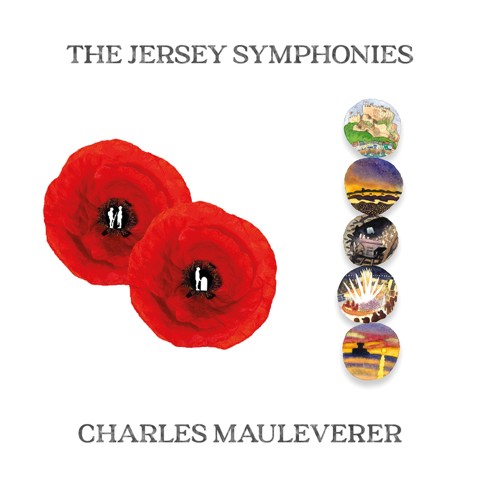

In two strikingly different orchestral works, Two Brothers and Five Curiosities, composer Charles Mauleverer explores the dual forces that shape our lives: the weight of history and the intimacy of place. One piece reaches back into the trauma, sacrifice, and overlooked narratives of the First World War, while the other celebrates the wonders of Jersey through five vivid musical postcards. Together, they reveal a composer deeply committed to empathy, memory, and the power of sound to illuminate forgotten stories.

From left to right: Lee Reynolds (guest conductor of Royal Scottish National Orchestra),

Simon Kiln (mixing and editing), Charles Mauleverer (composer)

The creative process behind these two symphonies unfolded along very different paths. As Mauleverer reflects, “The creative process for each of these symphonies was very different.” Two Brothers was shaped by an intensive research period in the years leading up to the Armistice centenary. He spent this time speaking with historians and journalists, digging through archives, improvising at the piano, and even attempting to contact descendants of Jersey soldiers. Much of the work took him across France and Belgium, where he retraced the footsteps of young men who had left the island to fight on the Western Front. In contrast, Five Curiosities was born from proximity and personal memory. “I spent much more time closer to home,” he says, “thinking about ways to experiment more with the orchestral palette.”

One meeting proved transformative to the emotional architecture of Two Brothers. Charles Mauleverer recalls being “intrigued by a couple of lines” in historian Ian Ronayne’s book Jersey’s Great War, which referenced the island’s youngest soldier. Ronayne, whom he calls “by a distance the most respected living authority on this subject,” provided further research that uncovered the story of Arthur and Charles Mallet. These two teenage brothers became the heart of the symphony. Arthur enlisted at fifteen, falsely recorded as nineteen. Charles, only nineteen himself, was shot while repairing barbed wire. Arthur, recently recovered from a shrapnel wound, was close enough on another assignment to witness his brother’s final hours. The composer notes, “It was critical in gaining an understanding of a forgotten part of our history,” especially one overshadowed by Jersey’s later occupation in World War II.

The research unearthed many revelations that altered the emotional direction of the music. He remembers the shock of discovering how many composers from both sides were killed in the Great War, as well as the tragic number of teenage soldiers who entered combat with little grasp of the reality ahead of them. Other images stayed with him: “the striking difference between the mindbogglingly enormous but unkempt German grave sites compared to the pristine Commonwealth graves,” and walking the bleak landscape where chemical weapons were first used. These impressions coalesced into a soundworld shaped as much by grief as by historical curiosity.

Writing the symphony was emotionally fraught. “Yes, I absolutely did feel emotionally swamped,” he admits. Living in Oxford, he was navigating personal challenges while preparing for a performance of his first symphony on climate change. At the same time, he was spending long hours with philosophers and early AI researchers, all against a backdrop of rising global conflict. This atmosphere seeped into the music, most strikingly in the work’s acoustic palindrome, an orchestral passage recorded in reverse to symbolise the cyclical senselessness of war. “I suppose it is a warning about the senselessness of loss and suffering that is necessarily tied to war,” he reflects.

If Two Brothers looks outward to history, Five Curiosities draws inward to Mauleverer’s own memories of Jersey. Each curiosity was chosen because it felt distinctively part of the island’s identity as he experienced it. “Perhaps these were like symphonic postcards of my own memories,” he says, “as well as experiences I’d encourage others to try when visiting the island.” These include the ancient Mont Orgueil Castle, the glowing coastal phenomenon of bioluminescence, the chilling concrete bunkers built under Nazi supervision, the exuberant “Moonlight Parade” of Jersey’s Battle of Flowers, and the rare, almost otherworldly magenta sunsets of St Ouen’s Bay.

Some movements unfolded swiftly. “Bioluminescence (second movement) came together quickly, perhaps because of its smaller instrumentation, while others were more complex. The jigsaw of the Moonlight Parade (fourth movement) likely sounds more complicated than it is,” he notes, whereas the final movement, Magenta Sunset, proved both difficult and deeply personal.

Recording the works brought new challenges and small triumphs. Arriving at sessions with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, he admits to initial nerves as “an unknown composer,” but the musicians’ quick enthusiasm eased the tension. Capturing the massive Taiko drums in “The Castle’s Secrets” caused every microphone in the room to distort, prompting creative problem-solving. Another unexpected discovery occurred when the orchestra was asked to slide their feet in rhythm in time with percussionists’ metal chains and sleigh bells; placing spare sheets of paper under their feet reduced unintended squeaks. One of his favourite moments came at Abbey Road, where engineer Cicely Balston helped reveal the acoustic palindrome in “1916” for the first time.

Across both works, the composer hopes that listeners feel connected to history, to place, to the fragile beauty of the world. As he says, “I hope they are inspired to continue discovering and learning, to find empathy and care for what we have in our precious and only known habitable planet.”

More information about Charles Mauleverer: http://www.charlesmauleverer.com/

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter