I hate to say it, but classical music still suffers from an image problem; an image crisis, in fact. Despite the best efforts of performers, promoters, venues and music lovers, the art form is perceived by many as elitist and only accessible to the few, not the many. It wasn’t always like this: when I was growing up in the UK in the 1960s and 70s, there seemed to be classical music everywhere – on the radio and TV (including live broadcasts of orchestral concerts and wonderful programmes presented by André Previn), in TV adverts and in shops.

André Previn

Now, if you mention you are a fan of classical music, people may look at you slightly askance. Or, as has happened to me on several occasions, ask, “did you come to like classical music as you got older?” – because, yes, the demographic for classical music is generally in the over-50 bracket. (I’ve always liked classical music, ever since I was a little girl.)

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Symphony No. 3 in A Minor, Op. 44 – III. Allegro (Ireland National Symphony Orchestra; Alexander Anissimov, cond.)

The Southbank Centre

Yet venues and promoters obsess about capturing that elusive (and often not especially interested) “younger/youth audience”, at the risk of alienating their core audience/demographic. One particularly depressing current example of this is London’s Southbank Centre, which is “leaning more heavily on describing classical music with a different language. Well-meant pieces to camera demystify the genre for this untapped, cynical and supposedly disinterested audience, the word ‘bangers’ used to describe popular works and sundry other nerve-jangling scores.” (Thoroughly Good blog). Alongside this, the venue has launched a classical music podcast for which “you don’t need a PhD to listen to”.

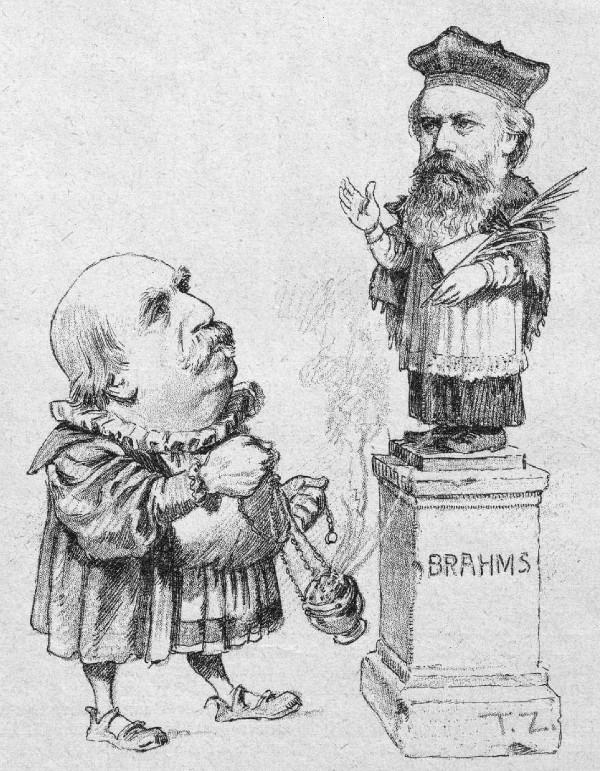

It has never been necessary to hold a PhD to enjoy classical music – or indeed any genre of music (though I might make an exception for jazz, which I find far more esoteric, exclusive and mystifying than classical music – but that’s just me!). Which is why I am drawn to this phrase, “audience needed – no experience necessary” (borrowed from this image):

The phrase “audience needed – no experience necessary” reframes classical music from something exclusive and intimidating into something open, welcoming, and participatory. It signals that listeners don’t need prior knowledge, training, or cultural “credentials” to belong – only curiosity and willingness to listen. Added to that, it doesn’t patronise or use “trendy” language. It tells newcomers that their lack of expertise isn’t a disadvantage but rather an asset, a starting point for discovery.

Musicians can use this message to bridge the gap between the performer and the audience. It frames them not as distant experts, but as fellow explorers eager to share something beautiful and immediate.

And instead of focusing on technicalities (composers, historical context, musical analysis), this kind of marketing can tap into the emotional and sensory appeal of live performance – the sound, the atmosphere, the shared moment. The phrase evokes a sense of adventure and discovery.

Richard Strauss: Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30, TrV 176 (Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra; André Previn, cond.)

It also connects with modern cultural values. Today’s audiences respond to inclusivity, authenticity, and accessibility. “No experience necessary” aligns with those values, suggesting classical music is for everyone – not a rarefied art form, but a living, breathing experience.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter