It seems to me that stand sharing is dead! Perhaps it started with the covid epidemic, but the advent and proliferation of iPad tablets is certainly contributing to going solo on a stand.

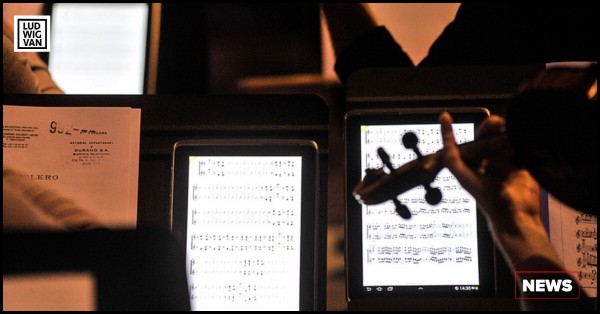

My chamber music colleagues are using them more. But what about orchestra musicians? Cellist Alan J Amira noticed that devices are being used by some New York Philharmonic players, and the use has increased from just a smattering of iPads a few years ago to as many as 20% of players more recently. The Brussels Philharmonic replaced sheet music with tablets in 2015.

The Brussels Philharmonic goes paperless © Brussels Philharmonic

Other orchestras, such as the Chicago Symphony, launched their series of small-ensemble virtual concerts, CSO Sessions, in 2020, when musicians started using iPads, and in March 2019, the Austrian Tonkünstler Orchestra used iPads and digital scores for the first time during a series of concerts at the Wiener Musikverein (Vienna) and the Festspielhaus St. Pölten. This is what they had to say. (Interesting to note that the librarian’s life becomes much easier too!)

Tonkünstler Orchestra playing from digital scores on iPad Pros – by Newzik

According to the newsletter Ludwig-van Toronto in 2021, “the Toronto-based Kindred Spirits Orchestra announced they have migrated to a fully digital library platform that will permanently replace their previous paper-based music library. The new system will save on average 20,000 sheets of printed paper annually and will make rehearsing and performing in post-pandemic times more convenient, healthier and safer by eliminating high-touch-point exchange of paper sheets, pencils, and erasers and by allowing hands-free page turns.”

From the musician’s standpoint, does sharing a stand with one iPad work? I checked with several colleagues. Eric Edberg, who plays regularly with seven regional symphonies in Indiana and Illinois, told me he has not seen string sections using tablets on individual stands, but that some brass and wind players do.

One of the orchestras Edberg plays with stipulates that you cannot use a tablet if you are in the first violins or cellos who sit at the edge of the stage, as the audience might be distracted by the tablets. Another orchestra, a string player indicated, will not allow iPads.

In Atlanta, the musicians of the Atlanta Symphony used iPads during the pandemic, but they are back to paper sheet music now, Joel Dallow told me. During those days, they realised how difficult it is for two people to read from one iPad while sharing a stand. New conflicts can arise, such as: Who gets to touch it? Who turns the pages? Who controls the foot pedal? And if a large enough iPad is brought in to share, when the brightness is increased, it consumes more battery power. They concluded that iPads seem to be designed for individual viewing, and the players decided to each bring their own iPad.

For musicians who play in theaters and are typically one on a part i.e. the only player, the iPad is simpler, some say, especially turning pages quickly. Cellist Christine Perkins hasn’t shared a stand in years. Although she’s happy with either paper or an iPad, for her, an iPad is easier, as her fingers don’t grip the paper very well. The exception is when she has to cobble multiple books together or when there are a complicated number of songs, then paper is easier. In a show such as Spelling Bee, where certain songs happen in an unpredictable sequence, Christine will have those songs on paper next to her iPad to be able to find them quickly.

A pianist/composer friend of mine told me about a way to program an iPad that can be set up to use facial expressions for page turns. Her piano student loves this feature. She winks to change the page – just be warned that the audience may think you’re flirting. A professional classical guitarist I know tried that in a recital. The iPad refused his advances and didn’t respond to his winks. It seems this feature doesn’t work as well if you must sit further away from the device, but I hear nose-scrunching and twitching works!

In a pit where space is an issue, a musician takes up less room with iPad use. He or she can avoid multiple cords and the clunkiness of a stand light, which in a pit you no longer need, and they can use a much smaller/thinner stand set-up. Jazz musicians who play in dark clubs find iPads great, but when you’ve got a gig to play outside and need to wear sunglasses, it’s almost impossible to see the screen!

For those of us who are of a certain age and old school, colleagues have indicated that it’s difficult to learn how to mark things quickly into the music during rehearsals. I know I wouldn’t know how. Someone told me: Janet, I like that I can highlight and make notes. My Apple Pencil allows me to do that, erase, or add fingerings, and in as many colours as I want. The markings will sync across devices, so the most up-to-date copy is available.

Minnesota Orchestra Principal Cello Anthony Ross, my stand partner of many years, explains why some of us may want to keep our sheet music.

Why are musicians using iPads on stage?

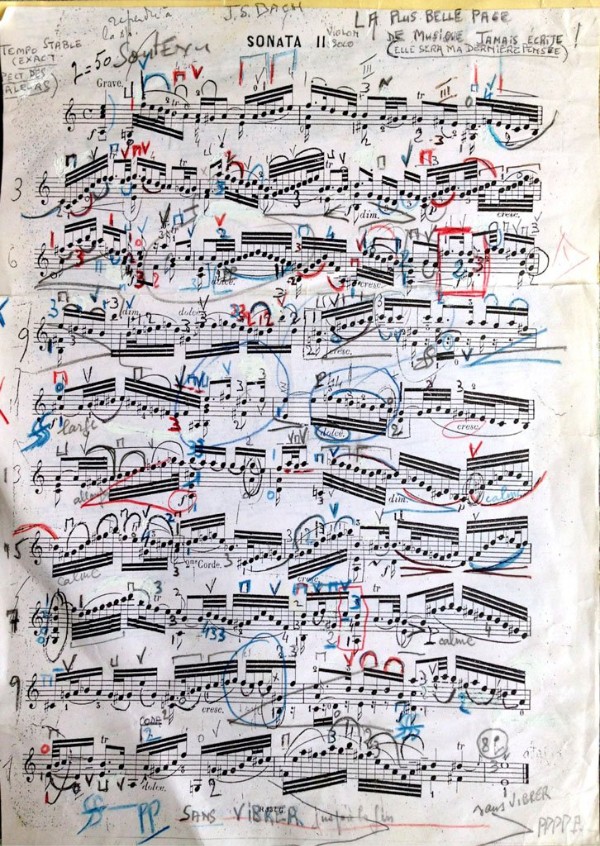

My library of music does include markings from years of performing certain works, and some pages look like this!

What happens when the iPad isn’t working or needs an update? A violinist told me about the time she had a quartet gig and ended up having to read the entire score, not individual parts, on a shared iPad. But what if you are in front of an audience? What would you do if the screen goes blank? Just give me paper, please.

You young players may not know how many issues we had using paper. We cellists and bass players, who sit quite close to a traditional music stand in order to “make” the page turns, resorted to photocopying multiple pages and sticking them together. What disasters were in store when we had to see across 3 or 4 pages and then try to flip the page?

or using multiple music stands!

Or we just lunged for the part, hoping we wouldn’t drop our bows. Note in this lovely Schubert Trio performance how violinist Yehudi Menuhin and cellist Maurice Gendron ace their quick turns at 4:42.

Schubert: Piano Trio No.1 – I. Allegro moderato

Let us regale you with some myriad page-turning horror stories.

Page Turning Horror Stories

Page Turning; It’s Harder Than You Think…

Turn and Turn

Pianist Jeeyoon Kim tells us about the never-ending stories of page-turners gone rogue and her search for a better solution!

Ipad or gvido? Which one to use for score reading? My method of using electronic score system

Teachers sing the praises of the iPad. In the past, they would have had to carry two or three bags of music weighing a ton. The iPad eliminates the need to carry bulky sheet music on the road too, and there’s the benefit that you probably won’t leave music behind, we hope.

What do audiences think about the use of iPads? From the spectator’s point of view, it might be aesthetically and visually more pleasing to have the musicians play without music stands— increasing the visibility of each musician and perhaps also their connection to the players.

There have been challenges to stand sharing even in the past. Some pieces are very difficult for two people to read. I’ve certainly encountered handwritten music that is quite illegible, and complex contemporary scores that have multiple, sometimes tiny and often confusing hieroglyphics to decipher.

But to get serious for a moment—the visual demands of orchestral musicians shouldn’t be underestimated even with using an iPad. Studies are underway to examine the effects of posture on vision. Musicians sometimes assume asymmetrical positions that not only affects their body adversely, but also music reading.

Normally, there should be a balance between the amount of eye movement in relation to head movement when we track an object either horizontally or vertically. An imbalance may occur when an instrumentalist chronically tilts or turns his or her head, or if a musician has to restrict his or her head movements due to the positioning required by the instrument. The eye that is further away for the music can become astigmatic over time.

A trombone player for example, may place his or her stand so that the bell of the instrument is unobstructed. The bell of the trombone may be in the left visual field, while the music is placed slightly to the right, which can lead to astigmatism in the left eye, unless the player can play standing and put the stand at a distance as in this beautiful excerpt of J.S. Bach’s Passacaglia for thirteen trombones.

Bach’s Passicagllia performed by the Trombones of the BBC Orchestra & Choirs

iPad or not, problems can develop with poor placement of our stands. Sometimes there just isn’t enough space on stage, and one must contort oneself to see the music and the conductor at the same time. Many of my string-playing colleagues indicate that they can see much better on one side of the music stand rather than the other. This is possibly from years of static postures favouring one eye—an excellent reason to advocate for revolving seating in the orchestra. You’ll be relieved to know that certain eye problems may be correctable with repositioning and eye therapy, but keep in mind that poor posture can affect our vision. Consider your head and neck positioning and maintain neutral neck positions to minimise neck tension and eye strain when placing your stand.

With proper placement, reading your music alone with your iPad might be the long-term solution to many issues. So, if sharing a stand is not already dead, it’s likely on its way out. For ensembles like Eighth Blackbird they’re not looking back!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter