‘A Never-Ending Adventure’

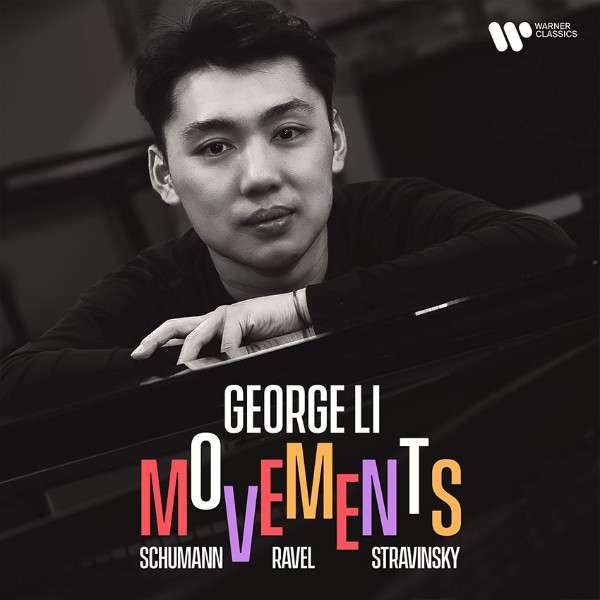

George Li © Simon Fowler

Listen to a performance of American pianist George Li’s and you will be left in no doubt as to his ‘staggering technical prowess, a sense of command and depth of expression’ (Washington Post). After winning the silver medal at the 2015 Tchaikovsky Piano Competition and receiving a coveted Avery Fisher Career Grant in 2016, George has gone on to perform around the world with orchestras including the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, London Philharmonic, Sydney Symphony and New York Philharmonic, playing at halls festivals across the US, Europe and Asia as a highly sought-after soloist and chamber music collaborator.

George Li plays Rachmaninoff Étude tableau in E flat minor, Op. 33 No. 6

George’s most recent release as an exclusive recording artist of Warner Classics was his 2024 album Movements, featuring dance-themed works by Ravel, Schumann, and Stravinsky. He completed studies in both literature and piano with the Harvard University/New England Conservatory dual degree programme in 2019, and we talked about the importance literature holds for George in his musical approach, along with the search for balance between technique and intuition.

How did you come to start learning the piano?

I grew up in a music-centric background – my parents don’t play instruments, but they really love and appreciate classical music, and I have an older sister who used to play the piano. I would accompany my sister to her piano lessons, and I started to show some enthusiasm at what was happening, so the teacher mentioned this to my mother, and I started lessons when I was four and a half.

It started off more as a hobby, as a way to teach me how to be disciplined and to have a structure in my life, but I did show a lot of interest in performing on stage from an early age. I also really loved the technical side of learning, of overcoming challenges from week to week… it was a bit like solving a puzzle, in a certain sense.

When did the piano begin to feel like more than just a hobby?

Music changed for me when I was 11 or 12. I remember there was one concert where I was playing Beethoven’s first piano concerto, the second movement, and suddenly I had this fleeting moment where I entered a different kind of space, beyond just memorising what my teacher had told me.

It was more like really being inside the music. It was a really life-changing moment, and from that moment on, I realised that music was more powerful than I thought, and I wanted to keep chasing that feeling again. That’s when I became a lot more serious.

How do you balance the technical side of things alongside the quest for those ‘special’ moments?

George Li © Paul Marc Mitchell

I think the more I study and practice music, the more I realise that when you’re practising, it’s like you’re in a science workshop, experimenting with different elements. You’re dissecting the piece in a very methodical way and trying to discover things, either new things in the piece or different interpretive ideas.

On the other hand, some people say that the piano is a form of acting. I think it’s true, but not in that visual way – it’s more in the process of how we interpret things.

An actor is trying to dissect a script and get to the essence of the part, and sometimes they do method acting to really get into the mindset of the kind of character they’re trying to play. I think in that sense it’s very similar to music: how, when we’re interpreting music, we’re trying to get to know the insides and outs of the piece, the material, so we can try to communicate as effectively as possible on stage.

Liszt: La Campanella by George Li

And this also includes the context of the work, the composer, and the cultural landscape of the time?

Absolutely. Its background, its influences, cultural references, and something I’ve learned by studying literature: how connected both the musical and literary worlds are, and the kinds of ideas that were circulating at the time.

In literature, when we analyse works, it’s always about connotations, like what a specific word refers to, or what kind of allusions a certain word draws from, and how different authors use it. It’s similar to the piano, when we’re making connections to a certain piece being from a certain world, and learning how to make sense of that. It’s almost like trying to make sense of a language that’s really abstract, but creating a story that we can communicate effectively.

How did your literature studies at Harvard tie into your work on the piano?

There was one moment, around my third year, where I was studying the Petrarca sonnets in my poetry class and the same week I was working on Liszt’s own Petrarca Sonnets [for piano], and it was interesting having such a direct overlap of material, seeing how language translates to the kinds of things that Liszt was thinking about before creating the song that was inspired by this text.

There are also many instances where maybe music and text don’t directly overlap as much, but you learn about the imagery that you read in a certain text, directly feeding into things that you’re studying on the piano and in music.

I think being able to process abstract music and trying to make sense of things, structuring it in a language that you can speak and communicate, helps me channel my feelings into the piece a little more directly.

So the link between text and music is still strong for you today?

Before Harvard, I definitely had a lot of feelings about a certain piece, but I couldn’t really find a focus to direct that energy towards. Studying literature has helped me channel my energy into something more tangible and easier to communicate through.

It was something that was more intuitive and hard to put into words, but when you have that kind of background of research and studying things, it’s a bit more grounded, and you can find the reason why, and then it becomes a little clearer.

Your 2024 recording Movements opens with Schumann’s Arabeske and then moves on to the Davidsbündlertänze. Can you talk about your relationship to Schumann’s music and your decision to include these pieces on the recording?

Schumann is a composer whom I got to know a lot more about over the pandemic. Before the pandemic, I had played Carnaval, but during the pandemic I studied the Fantasie and Davidsbündlertänze and the Arabeske, and what I loved about his music is that it’s very human.

It’s the way in which his mind is constantly changing between characters and moods. It’s so fluid. One moment you’re feeling pure bliss, and then the next it’s totally dark and anxious. You feel all these human feelings in such a short time frame. It’s what we go through every day.

We go through ups and downs in our lives and navigate through so many different emotions on the spectrum of feeling, and I think Schumann captures that really well.

This album was about dances. That was the theme, but I wanted to try and find pieces that had a narrative that could tell a story beyond ‘a set of waltzes’ or something. I try to see the Davidsbündlertänze more as a song cycle, as a way to link these pieces, these fragments, together. For me, at least as a performer, I think of it as a song cycle with all these dramatic elements and textures being put together. I think it helps to hold the album in a shape.

Do you have any plans for the next album?

I’m still thinking about what I would like to record. Recently, I did another programme around the theme of ‘images’, with Beethoven’s Tempest [Sonata] and Moonlight Sonata, Debussy’s Images and Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. I don’t know if I’ll record that, but it was a really fun programme to make and work through.

Recently, I’ve been spending a lot of time with Chopin’s third sonata, so I’ve really gotten to know it well. At some point, I’d also love to record Chopin’s Fantasie, so there are lots of ideas. Let’s see what develops.

George Li plays Chopin’s Nocturne Op. 27, No. 1

How do you decide what to work on next?

You can spend your entire lifetime just studying Schubert; there’s such a massive [piano] repertoire. It’s a blessing and a curse because you have such a wealth of things to choose from, but at the same time, it can also be very overwhelming. It’s an endless adventure.

Some things are more project-oriented, what people ask me to play, and then there are also things that I want to play, something that maybe I think is helpful for me to develop further. I’m starting to think I should do more Bach and play more Baroque music to get to the fundamentals of music-making. That might help me a bit more with structure, and maybe delving a little more into contemporary music and trying to see how music has evolved to today and trying to make sense of combining it with older pieces.

What do you do in your spare time?

I’m a big sports fan. My main sport is European football. I’m a big Arsenal fan and I try to watch as many of their games as possible. My brother and I always talk about the matches, during and after!

I also follow American sports – basketball, American football, and baseball. Boston, where I’m from, is a huge sports town. There’s always some sport going on. I grew up with a lot of baseball, and that was my big passion growing up.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter