The Importance of Being Respectful… To a Point

Vyacheslav Gryaznov

Pianist Vyacheslav Gryaznov was born on the island of Sakhalin, off Russia’s east coast, the southernmost point of which is a mere 25 miles from Japan’s northern tip. At the encouragement of his early piano teacher, his family relocated 4,000 miles west to Moscow, where he completed his studies at the Moscow State Conservatory – but that was only the first of two 4,000-mile jumps. Another leap west took Vyacheslav to the US in 2016, moving first to Yale to pursue an Artist Diploma, and then finally to New York, where he is now based.

Vyacheslav is busy both as a performer and arranger, and has released two albums featuring in turn Russian and Western piano transcriptions of works by composers including Prokofiev, Tchaikovsky, Monteverdi, Grieg and Ravel. I talk to Vyacheslav just before he heads to Vienna to record his concerto Rhapsody in Black with Wayne Marshall and the ORF Radio-Sinfonieorchester Wien, a work inspired by themes from Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess and conceived as a companion piece to the ever-popular Rhapsody in Blue.

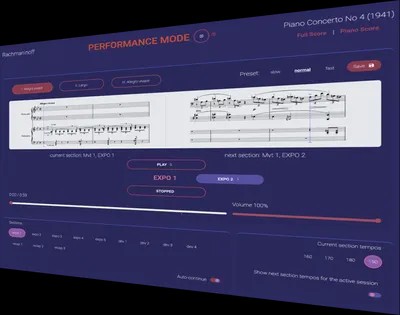

During the pandemic, Vyacheslav developed the G-Phil app, which allows pianists to play concerti with realistic orchestral accompaniment derived from high-quality sound libraries. Originally intended as a practice aid, Vyacheslav has since given public concert performances using the app, premiering G-Phil in a performance of Rachmaninoff’s Fourth Piano Concerto at Miami Piano Fest in 2023.

How did you find your way to music?

Vyacheslav Gryaznov

My family was not a musical family. My mother was a teacher of the German language, and my father was an engineer. He played the bayan, a kind of accordion with buttons, so that’s what I saw growing up.

I was born in Sakhalin, very far from the major cities in Russia. I hadn’t experienced going to concerts, and we didn’t have much musical culture growing up there. I didn’t make the choice to be a musician – I think it just happened.

My local teacher in Sakhalin, Irina Korzinina, was patient enough to guide me through some things carefully and without too much pressure. Eventually, when I was 11, my parents decided to move to Moscow so I could study music seriously. That was a big decision, not just for my musical career but my wider life.

I lost my father because of the move to Moscow. In Russia at that time, it was a very turbulent period after the collapse of the Soviet Union. He was a victim of some internal business mafia or something – we still don’t know to this day. So, my mother was raising me alone, and I was really fortunate with my teachers – that’s something I will carry with me throughout my life. I didn’t have many teachers, but each of them connected with important steps in my life.

My teacher, Manana Kandelaki, in Moscow was kind of my second mum. She was young and ambitious, and it was a perfect match – I needed to learn a lot. I hadn’t performed any concerts, I didn’t know the standard repertoire required by the music schools in Moscow, so she basically taught me from scratch.

I was catching up for a while, for a couple of years, and I consider that very useful in terms of problem-solving skills. My teacher discussed everything with me, and this information, this actual dealing with all the issues, using explanation and trial and error, helped me to be as independent as I think I am now.

So you carry what you learned from your earlier teachers into your own teaching practice today?

I wasn’t a prodigy, so I really had to go through everything myself, together with my teacher. Sometimes when you’re really gifted with something, you don’t know how you do it because it just happens, and then when you teach someone, you don’t understand why it doesn’t just happen to them. So I think it also really benefits my teaching career as well.

You are based in the US these days. What prompted the move?

I spent all of my ‘serious’ musical life in Moscow – music school, studying with Yury Slessarev at the Moscow conservatory, postgrad, everything. Then I worked as an assistant at the Conservatory for almost 10 years. I quit in 2018 when I decided to move to the United States to study at Yale – that was the point of no return.

We didn’t expect this Russia-Ukraine war would happen, and we didn’t expect that lots of musicians wouldn’t be able to go back, just because we posted something on Facebook. My friends and I are a little bit isolated now, but I hope it will change.

I think it’s important to talk about it and be open about it. I know many of my friends are afraid to talk about their relationships with the current situation openly – not because they don’t have an opinion, but because their opinion isn’t supported very well.

With music, we can communicate a lot of things without words, but the message sometimes is very clear. That’s why some Russian composers like Shostakovich sometimes had their music called rubbish or were told that it didn’t make sense, just because something wasn’t ‘correct’ in terms of their thinking.

Russia is a wild country. Sometimes in a positive way, sometimes not. Things are a little shaky everywhere these days, but at least here in the US, I am able to work freely and do my job.

Are there differences that you notice between Russia and America in terms of approach to performance?

My friend Konstantin Soukhovetski moved from Russia to the US over 20 years ago, and he told me that he remembers a contestant who was kicked out of a competition in the second round, but was given the opportunity to meet the judges, along with all the others who didn’t pass.

It was an opportunity to speak and introduce yourself, to get something out of it, so you don’t just go there for nothing. People don’t teach that in Russia, how to communicate with, for example, the people who support you, who help you.

They don’t talk, they don’t appreciate the moment, they don’t take the ‘advantages’ of their losses. I myself am still learning to communicate properly.

Does this include talking to the audience in concerts?

© gryaznoff.com

I am glad more and more musicians have started to talk with the audience during concerts, so we are in the same boat as them. I think it creates a different level of mutual understanding. You understand their vibe, they understand what you think, what you want to project. You’re tuned into the process much more.

Do you think we are moving away from the more traditional divide between performer and audience?

I don’t think it works any more, this ‘classical’ way of experiencing the concert when artists are somehow gods and the audience who are around them do not correlate with each other in any way. Those times are over, I hope.

Vladimir Horowitz was one of the first artists to explore this area among Soviet pianists. How he communicated with his audience is why he’s so loved. He was known for this vibe, quite simple, sometimes silly, just very open. It really makes a difference.

He showed himself as a human. It’s much more valuable to see a human on stage speaking to you. It’s there and it’s clear and it’s actually simple. That’s the message: that classical music is actually simple, because it’s about human emotions. All the composers were normal humans – maybe not that normal, but humans nonetheless!

Arranging is a prominent strand of your career. What is your process when creating an arrangement of a pre-existing work?

I think writing arrangements to produce something which is not a composition is a very interesting genre, actually. You kind of do something with other people’s music, but at the same time, it’s a very interesting and fragile world where you balance between artistic freedom and what you are as a person, while at the same time dealing with the music of another, so you have to be respectful of that.

Well, respectful to a point: if you’re too respectful, it won’t work. A famous example is when Tchaikovsky asked Rachmaninoff to transcribe one of his works. Rachmaninoff thought of Tchaikovsky as a god, as did many people at the time, so he did this job very meticulously, in a very ‘proper’ way, just following the score blindly. Tchaikovsky said that that wasn’t what he was asking of Rachmaninoff.

Maurice Ravel: La Valse

What do you believe was being asked of Rachmaninoff?

I think great musicians always want to hear their music in some sort of interpretation. This is the most valuable thing for any composer: to hear different opinions, to hear what kind of approaches can be made.

Sometimes, some of these chances are hidden, or correspond to something in the music, even if it wasn’t meant to be like that initially. Transcriptions, in my opinion, allow the musician to inject more personal understanding into a piece and, in a good way, ‘rewrite’ the piece.

Bach did it in his time, Busoni, Rachmaninoff, and Liszt. Liszt was probably one of the major influences in terms of piano arrangements. He brought this genre to the level of real pure art.

So, I’m trying to follow these giants in terms of how much freedom they had when looking into any sort of music, to understand it, and to produce their own product. It’s a really great way to refresh standard repertoire, and to offer audiences something from the performer, actually from the performer: not just an interpretation but something a little more.

Do you get a deeper understanding of the piece when you have to delve into the nuts and bolts of how it’s put together when arranging it?

Absolutely. Treating music in that way, even if I play the ‘original’, non-arranged work, you cherish the moment, and you play a particular piece according to who you are, right now. Writing cadenzas for classical concertos, for example, is a really useful thing.

I totally agree that this sort of ‘rewriting’ helps you to understand, to go deeper, into the musical piece, and cadenzas force you to rethink the whole movement, because your cadenza is the conclusion of the movement, and what you do there will impact what you do before. That’s why I highly recommend all musicians not to be afraid of trying to write their own cadenzas.

It’s fun, but I’ve found people are afraid of it sometimes. Once they start and try it, however, it’s a completely different story.

Claude Debussy: Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, arrangement for solo piano

Do you remember any piece that was particularly tricky to arrange?

I think, in general, chamber music, like quartets, quintets, and trios, is probably the most challenging to arrange, like when I was working on the Nocturne from Borodin’s String Quartet.

Chamber music works are basically polyphonic works written in a very pure and logical way. With the piano, you have to maintain the balance between piano textures and transparency, not to overload this pure material, while at the same time infusing it with textures – but tastefully!

That was a big challenge, actually: to find the right balance in this particular Borodin arrangement. In this arrangement, I ended up quite far from the original, but it usually happens like that. I start more or less together with the composer, and then I deviate, which makes sense, I think. I always try to give as much respect as I can to the composer and then to explore something else.

How did the G-Phil app come about?

G-Phil app

I played Rachmaninoff’s Third Piano Concerto with a second piano accompanying me in an exam at the Moscow State Conservatory, and I was exploring these orchestral sample libraries at the time. I have no idea why, but I came across these tools and just put the orchestral accompaniment on top of my playing. It sounded quite funny, but it was the first experiment in this area.

It was just a one-off thing, and I forgot about it for a while. And then, during the pandemic, we had much more free time than usual. I was learning a new concerto, Rachmaninoff’s Fourth Concerto, his last, which I’ve never played on stage, and it seemed to be much more challenging than all the other concertos just because it’s rarely played.

I wasn’t feeling very secure about it, so I decided to try to find a solution to train myself. I downloaded some demos of classical sample libraries, which are widely used, and just explored what was possible and what wasn’t. It turned out to be actually a really efficient and versatile tool for practising this piece.

It turned out to be the easiest of Rachmaninoff’s concertos for me because I learned the accompaniment properly, I learned internally what was going on in the orchestra. I knew what to listen to, I knew what to interact with.

I met musicians live in Romania for the first time after one year of the pandemic, when we were allowed to go out of the country, and the conductor told me that it seemed like I’d played this concerto many times. Well, kind of – but it was the first time live!

Then I decided to create a sort of system, so it wasn’t just a track for me that only I could use, but for people out there. I myself found it really valuable, so I thought, why not share it? One of my goals is to create an engaging, inspiring accompaniment, so when you try it during your own practice at home or even on stage, it turns out to work really well live. At the minute is the rubato, and freedom is hard-coded. You still have a selection of tempo, but you have to plan it a little. The flexibility is the next step.

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto 4

What do you do in your spare time?

My major hobby is probably designing apps! It takes a lot of time, but I really enjoy playing with the app, so I think it’s worth it. I think after developing this app, I kind of became a different musician, one who hopefully can communicate with the orchestra on a different level, one who is inside the team, not on the outside. I really like this feeling.

My son moved to the United States with me, and I’m very proud of him. He had to learn a lot of stuff himself – a new language, a new school, new friends – but he’s doing great.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter