When Léo Delibes died in Paris on 16 January 1891, the musical world lost a composer who had quietly but decisively altered the course of ballet music. His passing came at a moment of transition, as classical ballet was moving away from the light, decorative idiom of the mid-nineteenth century toward a more ambitious, symphonic, and dramatically integrated conception.

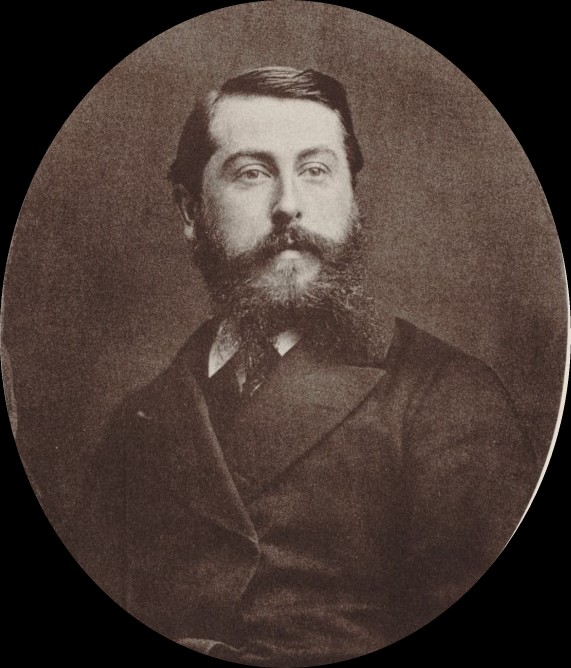

Léo Delibes

Delibes did not live to hear the full consequences of this transformation, yet his work stands unmistakably at its threshold. By the time of his death, the baton had already begun to pass to Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, whose great ballets would soon come to define the genre for generations.

To reflect on Delibes’ death, therefore, is to stand at a historical threshold, looking back to what ballet music had been before him, recognising what it became through his work, and anticipating what it would become after him.

Léo Delibes: Coppélia, “Dance of Swanilda and Frantz”

Ballet Transformed

Photo of the ballerina Giuseppina Bozzachi (1853-1870) costumed as Swanilda in the ballet Coppélia. Paris, France, 1870.

Before Delibes, ballet music was widely regarded as a subordinate art. Its primary function was to serve choreography, and its success was measured less by musical invention than by rhythmic clarity and adaptability.

Scores were expected to be melodically agreeable and structurally flexible, but rarely profound. Composers such as Cesare Pugni and Ludwig Minkus were skilled professionals whose music fulfilled theatrical requirements efficiently, yet seldom aspired to lasting artistic value. Ballet music, in short, was considered a craft rather than a compositional calling.

Delibes approached ballet differently. Trained at the Paris Conservatoire and steeped in the traditions of opera and orchestral music, he treated ballet as a legitimate musical genre worthy of care, imagination, and expressive nuance.

Without rejecting the functional demands of dance, he enriched ballet music from within, demonstrating that it could sustain melodic individuality, orchestral colour, and thematic coherence while remaining eminently danceable. His achievement lies not in overturning ballet tradition, but in elevating it.

Léo Delibes: Coppélia (Part 1)

Coppélia and Sylvia

Photo of the ballerina Olga Preobrajenskaya (1871-1962) in the title role of “Sylvia”

This conviction found its clearest early expression in Coppélia (1870). Though a comic ballet with a light-hearted plot, Coppélia is distinguished by its vivid orchestration and finely drawn musical characterisation.

Delibes employed national and folk dances, including mazurkas, czardas, and other stylised forms not as decorative exotica, but as expressive tools that shape character and narrative. He also made consistent use of recurring motifs, allowing the music to participate actively in storytelling.

By the time of Delibes’ death in 1891, Coppélia had become a benchmark. It was proof that ballet music could delight audiences while maintaining musical integrity and individuality.

An even greater step forward came with Sylvia (1876). Here, Delibes expanded the orchestra, enriched the harmonic language, and allowed the music an independence that astonished contemporaries.

The score unfolds with a sense of continuity and atmosphere previously rare in ballet, its melodies flowing seamlessly from one scene to the next. Dance historian Ivor Guest famously observed that in Sylvia “the music was not merely the chief interest; it was the only one.”

The remark captures the radical nature of Delibes’ achievement. Ballet music was no longer merely supportive; it had become central. That such a work could exist at all explains why Delibes’ death was felt not simply as the loss of a popular composer, but as the silencing of a pioneering musical voice.

Léo Delibes: Sylvia, Act III (Solo)

Building on Delibes

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

No composer recognised the significance of this achievement more clearly than Tchaikovsky, whose career overlapped almost exactly with Delibes’. The Russian composer openly admired Sylvia, and his oft-quoted remark that, had he known the score earlier, he “would not have written Swan Lake” should be read not as literal self-reproach, but as an expression of profound respect.

Delibes’ death in January 1891 coincided with Tchaikovsky’s completion of The Sleeping Beauty, the ballet in which he most fully realised his own vision of musical drama. This chronology is revealing. Delibes did not live to hear The Nutcracker (1892), nor to witness how decisively Tchaikovsky’s ballets would reshape the genre.

The Nutcracker

Yet Tchaikovsky’s achievements cannot be separated from Delibes’ example. The melodic generosity, attention to orchestral colour, and insistence that ballet music could sustain independent musical interest all point back to Delibes’ influence, an influence already firmly established by the time of his death.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: The Sleeping Beauty, “Waltz”

Music that Told the Story

Swan Lake

Tchaikovsky’s ballets represent a synthesis of Romantic musical language and integrated theatrical storytelling. His first major work in the genre, Swan Lake (1877), initially met with mixed reception, yet it introduced a new conception of ballet music as a unified musical organism.

Recurring thematic ideas, most famously the “swan theme,” lend the score a psychological and narrative depth unprecedented in ballet at the time. Music no longer merely accompanied movement, but it articulated emotional meaning.

In The Sleeping Beauty (1890), Tchaikovsky refined this approach with extraordinary assurance. The ballet’s structure is shaped by stylised historical dances like waltzes, polonaises, gavottes, and even archaic forms, which function both as spectacle and as dramatic symbols.

Thematic transformation and harmonic planning lend the work a symphonic coherence, aligning ballet music with the ambitions of opera and symphony. The Nutcracker (1892), though sometimes criticised for its episodic narrative, achieves remarkable brilliance through melodic invention and imaginative orchestration, creating an atmosphere of enchantment that has ensured its enduring popularity.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: The Nutcracker, “Sugar Plum pas de deux”

Contrasting Visions

Léo Delibes’ Coppélia

The contrast between Delibes and Tchaikovsky lies less in their shared Romantic idiom than in their differing artistic aims and cultural contexts. Delibes’ ballets are characterised by elegance, clarity, and refinement, as even dramatic moments retain a sense of balance and grace rooted in French theatrical tradition.

His scores function as ideal companions to dance while retaining a distinct life as orchestral music. Tchaikovsky’s works, by contrast, pursue broader emotional scope and psychological depth. His melodic language is richer, his harmonic explorations more adventurous, and his orchestration more expansive, reflecting a Russian Romanticism drawn toward intensity and dramatic contrast.

Structurally, Delibes tended to organise his ballets as sequences of characterful dances linked by colour and atmosphere rather than by large-scale thematic development. Tchaikovsky, on the other hand, relied upon recurring motifs and developmental processes akin to symphonic form.

In Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty, themes return and evolve across acts, reinforcing narrative continuity and situating ballet music closer to symphonic discourse than to traditional dance suites.

Delibes’ influence was acknowledged even by Tchaikovsky himself, whose correspondence reveals admiration for the French composer’s melodic invention and pacing. Yet Tchaikovsky’s ballets would, in turn, reshape the future of ballet music, inspiring choreographers and composers well into the twentieth century.

Figures such as George Balanchine and companies like the Ballets Russes drew on Tchaikovsky’s musical drama to forge new balletic aesthetics.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Swan Lake, Act II “Corps de ballet”

Legacy and Transformation

Léo Delibes and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky thus stand as two complementary figures in the transformation of ballet music. Delibes expanded its expressive palette and proved its artistic worth, while Tchaikovsky elevated it to symphonic and dramatic grandeur.

Remembering Delibes on the anniversary of his death is therefore not an act of nostalgia, but one of historical clarity. Ballet music as we know it today exists in the space Delibes opened, and in the future, his music helped to make it possible.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter