Today, 14 January, we commemorate the birthday of Mariss Ivars Georgs Jansons, born in Riga in 1943. Among the most distinguished conductors of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, Jansons’ artistry combined intellectual rigour, emotional depth, and ethical seriousness, qualities that secured his reputation as one of the defining interpreters of the symphonic repertoire of his time.

Shaped by his studies at the Leningrad Conservatory under Yevgeny Mravinsky, Jansons carried forward the precision and discipline of the Russian conducting tradition, yet infused it with warmth, clarity, and a deeply human touch.

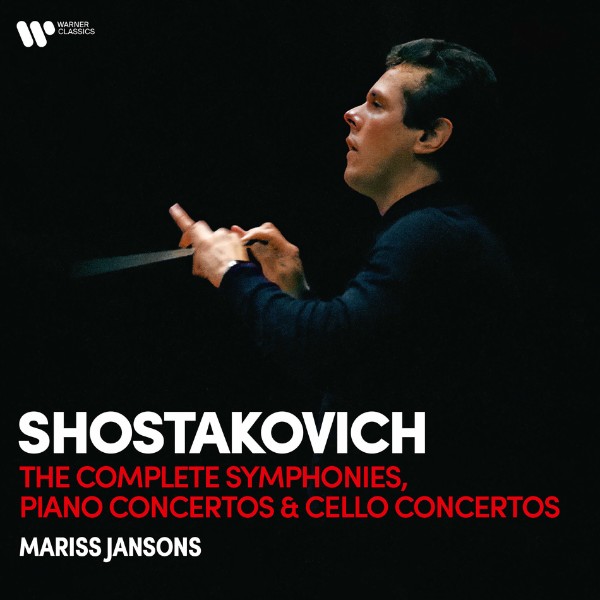

Mariss Jansons

As we commemorate his birthday, we honour Jansons’ deep connection with Shostakovich’s symphonies, where meticulous structural precision meets a breathtaking emotional sweep in a true hallmark of his artistry.

Mariss Jansons conducts Shostakovich: Symphony No. 10 (excerpt)

One Vision, Many Orchestras

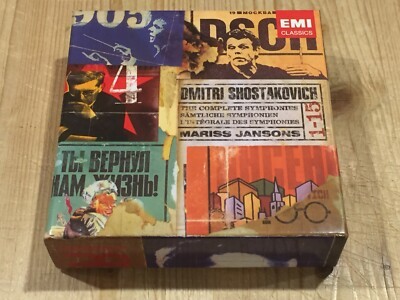

Nowhere is Jansons’ artistic profile more clearly articulated than in his complete recording cycle of Shostakovich’s fifteen symphonies, undertaken principally for EMI Classics over nearly two decades. This monumental project is widely regarded as one of the most ambitious and artistically coherent discographic achievements of the late twentieth century.

Unlike many complete cycles, which are anchored in a single orchestra and a unified institutional sound, Jansons’ Shostakovich project deliberately adopted a multi-orchestral strategy. The cycle brought together a remarkable roster of ensembles, including the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks (BRSO), the Leningrad/St. Petersburg Philharmonic, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and others.

Such an approach carried considerable risk. To sustain interpretive continuity across orchestras with distinct traditions, timbres, and rehearsal cultures required a conductor of exceptional clarity, stylistic authority, and communicative instinct.

Mariss Jansons: Symphony No. 5, (Moderato)

Discipline Without Diminution

A project of this magnitude needed someone capable of imposing a coherent musical vision without erasing the individual character of each ensemble. And Jansons succeeded precisely because of these qualities.

His Shostakovich readings are consistently praised for their taut structural logic, disciplined pacing, and meticulous attention to inner voices. Rather than foregrounding surface drama or rhetorical excess, Jansons allows tension to accumulate organically through careful control of tempo, rhythm, and orchestral balance. This approach enables the irony, bitterness, and anguish embedded in Shostakovich’s scores to emerge with compelling force.

In comparative terms, commentators have often located Jansons’ cycle in a carefully judged interpretive middle ground. It avoids the visceral rawness and overt brutality associated with conductors such as Kirill Kondrashin or the stern authority of the Russian school at its most uncompromising.

At the same time, it resists the enveloping Romantic warmth and expansive lyricism characteristic of figures like Bernard Haitink. Jansons’ Shostakovich is instead defined by disciplined articulation, rhythmic tautness, and a constant awareness of large-scale form. Emotional intensity is never absent, but it is always framed within an intelligible architectural design.

Dmitry Shostakovich: Symphony No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 10 – III. Lento (Rainer Kubnaul, violin; Ludwig Quandt, cello; Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; Mariss Jansons, cond.)

A Sustained Artistic Statement

Mariss Jansons

One of the most frequently cited strengths of the cycle is Jansons’s ability to impose interpretive unity across disparate orchestral forces. Despite the diversity of ensembles involved, the recordings feel less like a compilation of individual sessions than a sustained artistic statement.

Jansons’s impeccable sense of timing, his control of cumulative climaxes, and his insistence on transparency of texture give the cycle a remarkable internal consistency.

Scherzos bite without caricature, slow movements unfold with grave inevitability, and climaxes register with devastating clarity rather than bombast. Irony, sarcasm, and tragedy coexist within a disciplined expressive framework.

Dmitry Shostakovich: Symphony No. 9 in E-Flat Major, Op. 70 – V. Allegretto (Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; Mariss Jansons, cond.)

Recognition and Responsibility

The cycle’s critical success was matched by institutional recognition. It was highly acclaimed and included a Grammy Award for the recording of Symphony No. 13, “Babi Yar,” with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra.

This performance, featuring bass Sergei Aleksashkin and the BRSO Chorus, stands as one of the most powerful achievements in Jansons’ discography. In a work inseparable from political trauma and cultural memory, Jansons demonstrates his exceptional ability to integrate vocal and orchestral forces while maintaining moral gravity and musical coherence.

Individual symphonies within the cycle further illuminate Jansons’ interpretive priorities. Symphony No. 8, Op. 65, one of Shostakovich’s most harrowing statements, is emblematic of the composer’s intensely personal voice. Jansons’s performances have been described as “taut” and “fluid,” balancing grief and formal tension with extraordinary control.

Rather than yielding to raw despair, Jansons shapes the symphony’s long spans with an unerring sense of proportion, allowing its bleak narrative to unfold with inexorable logic. His rhythmic discipline and carefully calibrated climaxes reveal the work’s emotional devastation without sacrificing coherence for momentary effect.

Dmitry Shostakovich: Symphony No. 13 in B-Flat Minor, Op. 113, “Babi Yar” (Sergei Aleksashkin, bass; Bavarian Radio Chorus; Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; Mariss Jansons, cond.)

History Without Reduction

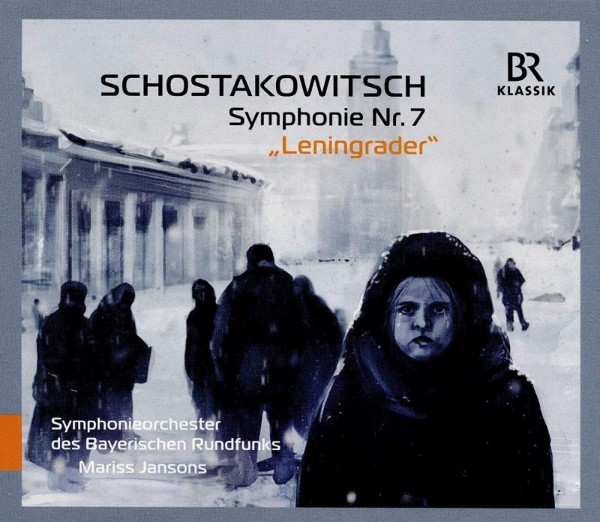

This balance is equally evident in works with strong extramusical associations. Symphony No. 7, “Leningrad,” composed during the Nazi siege of the city, occupies a special place in Shostakovich’s reception history. Jansons’ Soviet upbringing and his reflections in interviews on Shostakovich’s portrayals of struggle, hope, and despair lend his interpretations a particular authenticity.

Yet he consistently resists purely programmatic readings. Rather than treating the symphony as a historical document alone, Jansons emphasises how its internal musical tensions articulate a broader, universal human experience of endurance under pressure.

Scholarly commentary has situated Jansons within a lineage of conductors shaped by Russian traditions while remaining responsive to modern expectations of textual clarity and expressive nuance. Jansons frequently invoked the authority of musicians “who knew Shostakovich personally” when discussing questions of tempo and phrasing.

At the same time, his interpretations avoid slavish literalism. Instead, they reflect a dialectic between historical awareness and artistic judgment, a position that aligns closely with contemporary performance studies approaches to Shostakovich’s complex musical language.

Dmitry Shostakovich: Symphony No. 7 in C Major, Op. 60, “Leningrad” – I. Allegretto (Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; Mariss Jansons, cond.)

Restraint Reconsidered

Not all criticism has been unqualified. Some reviewers have noted a perceived coolness at moments of extreme affect, particularly when comparing Jansons with more overtly impassioned interpreters such as Mravinsky or Kondrashin.

Yet this restraint has increasingly been understood as a defining strength rather than a limitation. By resisting emotional inflation, Jansons allows each symphony’s structural narrative to speak with clarity and integrity.

In the broader landscape of Shostakovich performance practice, Jansons’ symphonic cycle endures as both a reference point and a subject of ongoing scholarly interest. It encapsulates the interpretive priorities of the late twentieth century, including structural clarity, orchestral precision, and emotional authenticity grounded in discipline rather than excess.

More than a historical document, it remains a living testament to Jansons’s enduring influence on the repertoire that shaped his artistic identity. It also pays tribute to a conductor whose legacy continues to resonate with quiet authority and profound humanity.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter