In the 1930s, Peter Burra was a rising star in British letters. But his death at the age of twenty-seven in an airplane crash brought those hopes to a sudden, violent end.

Though Burra’s life was cut tragically short, his influence endured long beyond his death. For one, his death helped to bring together composer Benjamin Britten and tenor Peter Pears, who would go on to forge one of the most remarkable creative partnerships in the history of classical music.

Peter Burra

But it all started with Peter Burra. Today, we’re diving into the story.

Peter Burra’s Childhood and Schooling

Peter Burra was born on 25 August 1909 in Oxfordshire to a corn merchant named William Pomfret Burra and his wife, Ella Mara Lucker.

William died in 1911, so Peter would have only had very foggy memories of him, if he had any at all.

Burra had a twin sister named Helen, who went by the nickname Nella. Like her brother, she made a life for herself in the arts, becoming a singer and actress.

As a teenager, Burra attended Lancing College, a school for teenagers located in West Sussex.

Befriending Peter Pears

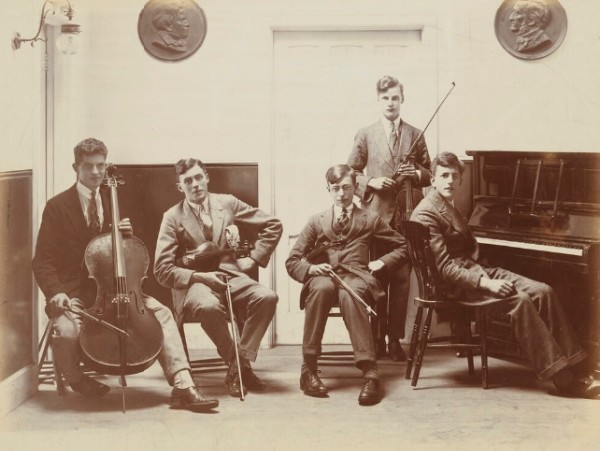

Peter Burra standing next to Peter Pears at the piano

While there, Burra befriended a fellow student named Peter Pears. Pears, in turn, grew close to Nella, with Nella and Pears often feeling like siblings themselves.

As a teenager, Burra studied the violin and played in the Lancing Chamber Music Society. (Pears played piano and sang.)

After they graduated, Burra and Pears went up to Oxford together. However, the academic focus of Oxford and the lack of focus on practical musical training generally failed to appeal to Pears, and he ended up leaving Oxford, taking a position as a schoolteacher instead.

In 1929, Nella urged Pears not to sleepwalk into an anonymous career as a teacher; she felt he was capable of much more. In part due to Nella’s belief in him, Pears decided to study singing more seriously, and he enrolled at the Royal Conservatory of Music for a time.

Burra’s Early Professional Projects

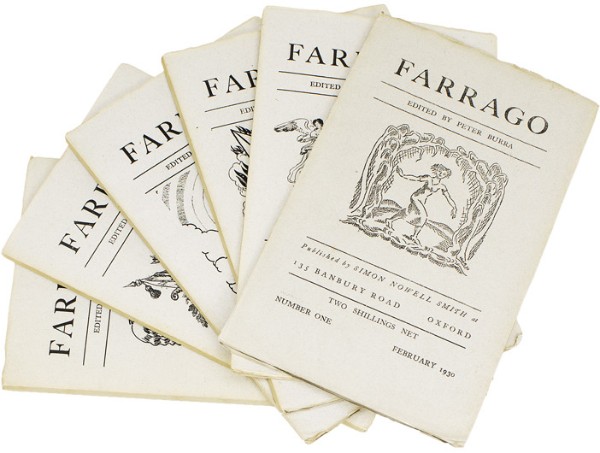

The Farrago magazines

Between 1930 and 1931, Burra was the editor of Farrago, a magazine featuring the work of some of the best artists and writers in Britain, published in Oxford.

In addition to working as an editor, he became interested in writing about history. In 1934, at the age of twenty-five, he published Van Gogh, a biography of Vincent Van Gogh, and two years later, he published Wordsworth, Great Lives. These two biographies were received very positively.

Then, starting in the early 1930s, he became a special arts correspondent for The Times.

He traveled to Germany, reporting on the arts there. He was shaken by what he witnessed as the Nazis came to power.

After seeing Hitler speak in Munich in 1932, he wrote back home with eerie prescience:

“It was the most repulsive exhibition I’ve ever seen… I think it advisable to see as much of the country as possible now. It will certainly be uninhabitable in a few months.”

Traveling to Barcelona and Meeting Britten

Lennox Berkeley with Benjamin Britten © lennoxberkeley.org.uk

In the spring of 1936, Burra found himself traveling to Barcelona to cover the International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM) Festival.

While there, he met an up-and-coming composer named Benjamin Britten, as well as Britten’s friend and colleague, fellow composer Lennox Berkeley.

During that trip, Britten and Berkeley spent time sightseeing together in Barcelona, gathering material for their jointly written orchestral suite Mont Juic.

Britten/Berkeley: Suite Mont Juic III, IV

At the time, Burra’s old friend Peter Pears was living in Burra’s cottage in Bucklebury Common in the Berkshire countryside. On 1 May 1936, while covering the Festival, Burra wrote to Pears mentioning that he had met both Britten and Berkeley.

Britten quickly became close to Burra, referring to him as “Dear” in his letters, which was meaningful terminology for the emotionally reserved composer to employ. In his journal, he commented enthusiastically about Burra’s ability to make friends and gain the trust and confidence of others.

In November 1936, in an issue of the Group Theatre Paper, Burra reviewed a production of “The Agamemnon of Aeschylus” with music composed by Britten. It was a promising start to the professional relationship between one of England’s most promising young composers and one of its most promising young critics.

Adding a certain kind of frisson to their interactions is the fact that the two men were attracted to each other. However, as best we know, they never acted on it.

The Spanish Civil War and a Tragic Accident

A few months after the ISCM Festival in Barcelona, the Spanish Civil War began in earnest.

In July 1936, a group of Spanish military officers (from the Nationalists) mounted a coup against the democratically elected government (known as Republicans).

Hitler and Mussolini supported the Nationalists, while leftists and anti-fascists threw their support behind the Republicans.

The war was an early indicator of the tensions that would ignite World War II just a few years later, and interest in the conflict spilt over the Spanish borders.

In fact, British author George Orwell actually went to Spain to try to stem the tide of rising authoritarianism in Europe, and he wasn’t alone.

Like Orwell, Burra also wanted to go to Spain to fight against the fascist threat. So he decided to learn how to fly.

But tragedy struck during his very first lesson on 27 April 1937. A light aircraft piloted by his friend and instructor crashed, killing both. Burra was only twenty-seven years old.

After Burra’s shocking death, E.M. Forster dubbed him “the best critic of his generation” and remarked “had he lived he would certainly have won fame as a creative artist, too.”

Britten’s Reaction to Burra’s Death

Benjamin Britten and Lennox Berkeley were devastated at Burra’s death. They dedicated the orchestral suite they’d been working on since the Barcelona trip, Mont Juic, to Burra’s memory.

Britten also stepped in to write music for a memorial concert: he composed a setting of a Burra poem in tribute to him: “Not even summer yet.”

The poem is heartbreaking:

Not even summer yet

Can make my quite forget

That still most blessed thing,

The early spring.

I watch’d the red-tipped trees

Burst into greeneries;

Saw the swift blossom come

Like sea dissolv’d in foam.

But in the lover’s ways,

The summer of his days

Is come from such a spring

As poets cannot sing.

Burra’s twin sister, Nella, agreed to sing it, but apparently, she only did so once because it was so emotional.

Not Even Summer Yet by Benjamin Britten

Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears Meet

Portrait of Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears

Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears, both grieving the sudden loss of their brilliant friend, had met briefly at a party in early 1937. Now they were suddenly tasked with clearing Burra’s possessions and papers out of the cottage.

The loss hit both men hard.

Pears was living in Burra’s cottage, and had obviously known him for much longer than Britten ever had.

But Britten was also emotionally tender at the time: his beloved mother had died just a couple of months earlier, and his diary is clear that he was in deep mourning for her, too, on top of the loss of his crush Burra.

Why did Britten and Pears volunteer to clean out the house? It has been suggested that they wanted to censor references to Burra’s homosexuality. If proof about his orientation ever got out to a wider audience, it would have a negative impact on Burra’s reputation. And both Britten and Pears were gay themselves, so they’d know what needed to be destroyed and what could slide.

The experience of sorting through their dead friend’s papers created a deep emotional intimacy. Soon, Britten and Pears became good friends.

More importantly for music history, though, Pears became a major creative inspiration for Britten.

Soon after their meeting, Britten had composed a setting of Emily Brontë’s poem “A thousand gleaming fires” for tenor and strings. It would be the first piece of many that he wrote for Pears’s voice.

Benjamin Britten: The Company of Heaven – No. 7. A thousand gleaming tires (Peter Barkworth, narrator; Sheila Allen, narrator; Cathryn Pope, soprano; Dan Dressen, tenor; Christopher Herrick, organ; London Philharmonic Choir; Philip Brunelle, cond.)

As for his part, Pears found Britten’s belief in him inspiring, too. It helped him to take his music-making seriously.

Britten and Pears Begin Their Decades-Long Romance

Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears

After Burra’s death, Britten and Pears moved in together.

In April 1939, two years after Burra’s death, Pears traveled to America with Britten on a concert tour.

After two full years of friendship, they regarded a stop in Grand Rapids, Michigan, as the start of their romantic relationship. For the rest of their lives, they would be both personal and professional partners.

Would that bond have been the same without Burra’s tragic death? And how would Britten’s music have developed differently without Pears’s love, support, and advocacy? What would have happened if Britten had started dating the talented young critic Burra instead?

For those fascinated by classical music counterfactuals, it’s all irresistible to think about.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter