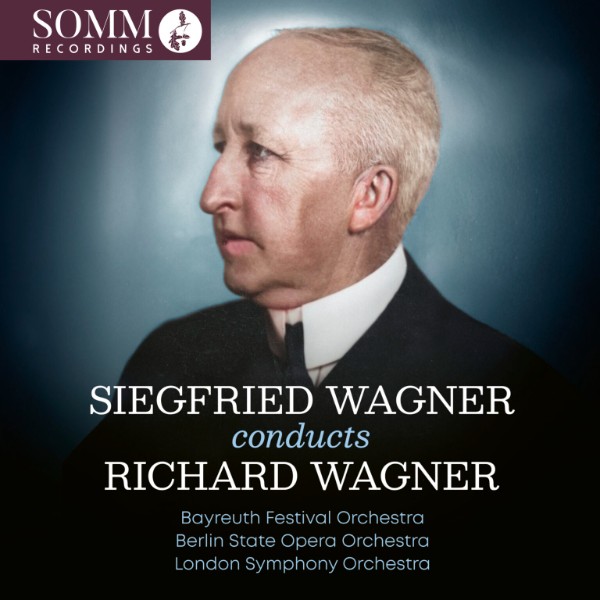

The past is a different country, and sometimes this becomes clearest in the most unexpected places. We spoke recently with Lani Spahr, who did the audio restoration on the recent SOMM Recording Siegfried Wagner Conducts Richard Wagner, taking recordings made in 1925 through 1927 and giving them a new start in their second century.

Siegfried Wagner and Cosima Wagner, ca 1929

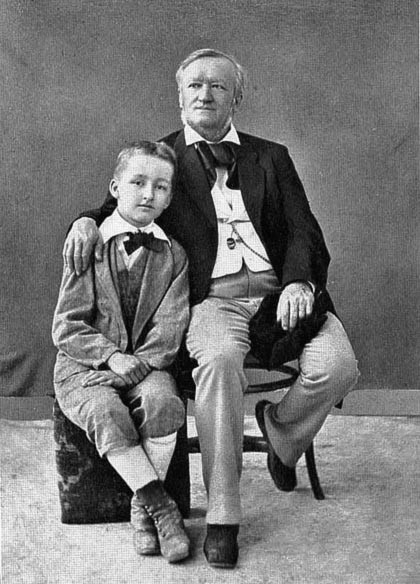

Richard Wagner and the young Siegfried

Lani Spahr

The CD contains excerpts from the first two operas of The Ring Cycle, Parsifal, Tannhäuser, Lohengrin and Tristan und Isolde. In addition, we have Richard’s gift to Cosima, the Siegfried Idyll and his 1864 work for military band, Huldigungsmarsch. A final track brings us the overture from one of Siegfried’s 12 operas: Der Bärenhäuter, Op.1.

Starting with the original matrices for these electrical recordings, Spahr brings us music from a century ago.

Siegfried Wagner was Richard Wagner’s eldest son (after his two daughters, Isolde and Eva). Named for the hero of The Ring Cycle, Siegfried (1869–1930) made his career as a composer and a conductor, abandoning his early studies in architecture. As a conductor, he appeared at Bayreuth as early as 1892. He was an assistant conductor at Bayreuth in 1894, was appointed associate conductor in 1896, and became artistic director of the Bayreuth Festival in 1908, following his mother, Cosima, in that position. At Bayreuth, he came under the influence of not only Cosima but also the conductor Hans Richter, who instilled in the heir the traditions of conducting and opera production expected at Bayreuth. Siegfried conducted his first Ring cycle at Bayreuth in 1896, the first full performance in the cycle in 20 years. His career as the true guardian of the Wagner inheritance seemed assured at Bayreuth, and his recordings seem to bear this out.

Recordings from the early 20th century come in two varieties, acoustic and electrical, and both are present on this recording. We discussed the difference between electrical and acoustic recordings: electrical recordings are much like today’s recordings, made with microphones and amplifiers; acoustic recordings were the ones made in small rooms with large recording horns.

Acoustic recording (Library of Congress)

While all the Richard Wagner on this disc is done from electrical recordings, the recording of the overture to Siegfried’s opera Der Bärenhäuter came from an acoustic recording. The expectation, from too many poor transfers from acoustic recordings, is that they sound more like ‘frying sausages’ than a real sound recording. With his years of experience in recording acoustics, Mr. Spahr is able to defeat the limited frequency response of the original recording and give us a recording that can actually be listened to, rather than endured.

We asked if he faced any surprises in his work on the Siegfried Wagner recordings, and he said nothing more than the usual generic problems, but did note that every recording company had its own distinctive way of organising its equaliser. Columbia, HMV, and Parlophone (to mention the three matrix sources on this recording) each had their own sound. Also, we discussed the fact that ‘78 doesn’t mean 78’, i.e., when we talk about a ‘78-recording’, we’re not necessarily talking about record speed as much as format. ‘78’ was an approximation of a record speed. What was more important was the pitch of the recording.

It turns out that pitch is more a national characteristic than a universal one. The three orchestras on this recording, the Bayreuth Festival Orchestra, the Berlin State Opera Orchestra, and the London Symphony Orchestra, recorded between 1925 and 1927, had different pitch ideals, and this continues up to this day. German orchestras tended to be higher, such as A=446 cycles per second; US and UK orchestras tend to be closer to A=440. Mr. Spahr noted that in his experience as a Baroque oboist, French Baroque tuning might be closer to A=392, almost a whole step down in pitch than what we’re used to.

In creating his audio restoration and discarding speed for attention to pitch, Mr. Spahr becomes the ‘invisible soloist’. He gives the conductor and his orchestras their true voice, coming to us from a century ago. As the direct heir of his father, his father’s opera house, and of his mother’s artistic direction, Siegfried Wagner has much to show us in these recordings. We can get an appreciation for his use of tempo, his ability to shape the passage work, and how he lets the music sing. We may have an initial difficulty in listening to an orchestral sound that is far different from today, but it’s in the details that the value is found.

Siegfried Wagner conducts Richard Wagner

SOMM Recordings: Ariadne 5043-2

Release date: 19 September 2025

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

CONTENTS

Richard Wagner

Das Rheingold, WWV 86A: Entry of the Gods into Valhalla (orchestra version (Berlin State Opera Orchestra) (1927)

Die Walküre, WWV 86B, The Ride of the Valkyries (Berlin State Opera Orchestra) (1926)

Die Walküre, WWV 86B, Wotan’s Farewell & Magic Fire Music (Berlin State Opera Orchestra) (1927)

Parsifal, WWV 111, Good Friday Spell (Bayreuth Festival Orchestra; Parsifal: Fritz Wolff; Gurnemanz: Alexander Kipnis) (1927)

Parsifal, WWV 111, Prelude to Act III (Bayreuth Festival Orchestra) (1927)

Parsifal, WWV 111, Good Friday Spell (orchestral version) (Berlin State Opera Orchestra) (1926)

Siegfried Idyll, WWV 103 (London Symphony Orchestra) (1927)

Huldigungsmarsch, WWV 97 (London Symphony Orchestra) (1927)

Tannhäuser, WWV 70: Entry of the Guests (Berlin State Opera Orchestra) (1927)

Lohengrin, WWV 75: Prelude to Act I (London Symphony Orchestra) (1927)

Tristan und Isolde, WWV 90: Prelude to Act I and Liebestod (orchestral version) (Berlin State Opera Orchestra) (1926)

Siegfried Wagner

Der Bärenhäuter, Op.1: 6 Overture (Berlin State Opera Orchestra) (1925)