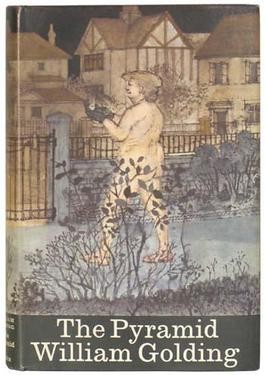

Adam Schoenberg’s Picture Studies

In a modern version of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, where he walks around an exhibition of his friend Viktor Hartmann’s paintings, American composer Adam Schoenberg (b. 1980) created his own tour around the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, Missouri. Established in 1933, this museum was founded with money from the estate of newspaper publisher William Rockhill Nelson, who specified that his estate was to go towards purchasing artwork for public enjoyment. Originally, two art museums, the Nelson’s estate and that of Mary McAfee Atkins, were combined to make a single major art museum.

On commission from the Kansas City Symphony and the Museum, Schoenberg was invited to write a ‘21st-century Pictures at an Exhibition’. In honour of Mussorgsky’s original work for solo piano, four of the 10 movements were written as piano etudes and later orchestrated. As with Mussorgsky’s work, this one is built on a structure that connects each movement within an overall framework for the whole work.

Adam Schoenberg (photo by Sam Zauscher)

Picture Studies, completed in 2012, is based on 4 paintings, 3 photographs, and one sculpture.

He begins with Intro, a brief ghostly entrance to the museum.

Adam Schoenberg: Picture Studies – I. Intro (Kansas City Symphony; Michael Stern, cond.)

His first piece of art is by an American painter, Albert Bloch (1882–1961), and his image of three French clowns. His Three Pierrots, No. 2, painted in 1911, shows three figures in motion. Each faces a different direction. They have mask-like faces and lack the usual black buttons of a Pierrot costume.

Albert Bloch: Die drei Pierrots Nr. 2 (The Three Pierrots No. 2), 1911 (Nelson-Atkins Museum)

Schoenberg uses the idea of three as the basis for his movement, Three Pierrots. He sees them as comedic, naïve, and excited and uses the trio to create a triad that will, like a clown in motion, be turned upside down, sideways, and ‘twisted in every possible way’.

Adam Schoenberg: Picture Studies – II. Three Pierrots (Kansas City Symphony; Michael Stern, cond.)

Venezuelan-American artist Kurt Baasch (1891 –1964) took a picture of a street corner in 1913. In this vintage platinum print, two men and two women walk in different directions. The older woman is in the middle of the street, dressed all in black (or a dark colour), holding an umbrella against the sun. The younger woman has just mounted the pavement and is walking in a determined manner, wearing a light-coloured hat. In front of her, at a 90° angle to her, is a man in a straw hat, walking with his head down, as though he’s hurrying. A second man, holding a newspaper, is about to come to the edge of the sidewalk. He seems to be looking at one of the two women and has a much more leisurely pace. From the strong sun and the straw hats, we know this is summertime (straw hats were destroyed on Labour Day weekend in the US at this time).

Kurt Baasch: Repetition, 1913 (Nelson-Atkins Museum)

Schoenberg uses the title, Repetition, to give us a work very much in the minimalist style. The composer creates a movement that is very much like the before and after of taking a picture. In his work in ABA form, B is the moment the shutter clicks and captures this image.

Adam Schoenberg: Picture Studies – III. Repetition (Kansas City Symphony; Michael Stern, cond.)

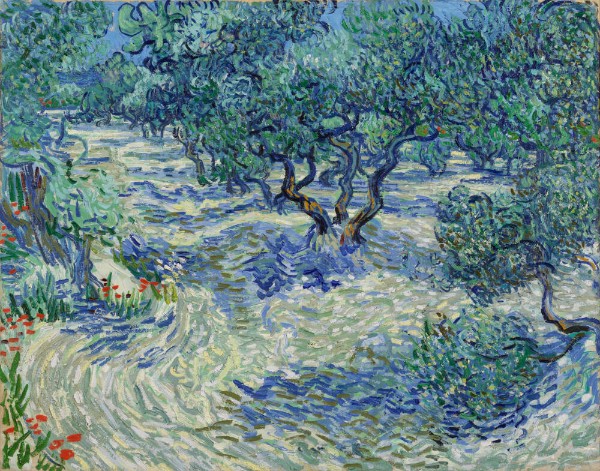

Dropping back a quarter century, we’re in Arles with Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh (1853—1890). His olive trees sprawl out, catching the light and hinting at their fruit to come. The brilliant greens and blues have hints of the black treasure to come. In the bottom left corner, red flowers provide a contrast with the green and blue sea.

Vincent van Gogh: Olive Trees, 1889 (Nelson-Atkins Museum)

Schoenberg sees van Gogh’s olive grove as a place brimming with life. Perhaps lovers meet here? His delicate musical lines catch the sun in the trees, the shadows that fall around the ground, and a hint of the flowers’ colour

Adam Schoenberg: Picture Studies – IV. Olive Orchard (Kansas City Symphony; Michael Stern, cond.)

Wassily Kandinsky’s Rosa mit Grau (Rose with Gray) from 1924 returns us to the 20th century. The left side of the painting is full of dark jagged lines, while the right side is scalloped in lighter colours. A rose and a grey circle in the middle are the focus of the action. Is it a parody of a man with his head turned at an angle, holding up his cane? Is the brown figure at the top right of the circle another talking head? The image is animated and interrupted. Lines advance and recede.

Wassily Kandinsky: Rosa mit Grau (Rose with Gray), 1924 (Nelson-Atkins Museum)

Schoenberg’s Kandinsky is a battleground that is ‘geometrically fierce, angular, sharp, jagged, violent, jumpy, and complex’. His focus on the edginess leads to a work that is full of block structures.

Adam Schoenberg: Picture Studies – V. Kandinsky (Kansas City Symphony; Michael Stern, cond.)

American artist Alexander Calder (1898–1976) is known for his moving sculptures, called mobiles, and this work combines a mobile with a natural form. Two arms, one black and one red, are made of wood and reach up to support a spider-silk–thing wire. It supports four disks and is so fragile that the slightest breath of air sets it in play. The motion means that every second, it is a new thing, a new image, a new arrangement.

Alexander Calder: Untitled, 1936 (Nelson-Atkins Museum)

Schoenberg takes us to Calder’s World. Time stops and yet is filled with a delicate motion. There’s a shimmer in the sound that imitates the motion of the air-activated mobile, its elusive action making its own subtle movement in the air.

Adam Schoenberg: Picture Studies – VI. Calder’s World (Kansas City Symphony; Michael Stern, cond.)

Only 10 years later, we have Spanish painter Joan Miró’s Women at Sunrise, one of his experiments in ‘pure psychic automatism’, a ‘form of doodling without the intervention of rational thought’. The faces are all different shapes, but the sun is present and throws shadows.

Joan Miró: Women at Sunrise, 1946 (Nelson-Atkins Museum)

The composer takes us to a world that is both childlike and wild. He works towards a tribal interpretation of Mirò’s world.

Adam Schoenberg: Picture Studies – VII. Miró (Kansas City Symphony; Michael Stern, cond.)

We return to our opening interlude, now less ghostly and louder, with more of the orchestral participation.

Adam Schoenberg: Picture Studies – VII. Interlude (Kansas City Symphony; Michael Stern, cond.)

Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto (b. 1948) is best known for his images of the sea and sky where the horizon splits the image. In this picture of the Atlantic Ocean, taken from the Cliffs of Moher in Ireland, the sea fog obscures the horizon, making the sea blend into the sky. As we recede from the shore, the ocean smooths out to become the sky. This image is from his series Time Exposed.

Hiroshi Sugimoto: Time Exposed: Atlantic Ocean, Cliffs of Moher, 1989 (Nelson-Atkins Museum)

Picking up on the slight motion of the ocean, Schoenberg rocks us in the gently moving waters. He uses a repeated gesture, the ostinato, to convey the motion.

Adam Schoenberg: Picture Studies – IX. Cliffs of Moher (Kansas City Symphony; Michael Stern, cond.)

The final work is one of the earliest, dating from 1889. American photographer Francis Blake (1850–1913) was an innovator and inventor, contributing seminal inventions to the Bell Telephone Company that aided its success. He started experimenting with high-speed photography in 1886 and was able to capture quickly moving actions. At a time when photographic subjects had to hold still for the camera to capture their image, this picture of pigeons in flight was groundbreaking.

Francis Blake: Pigeons in Flight, 1889 (Nelson-Atkins Museum)

Schoenberg closes his procession around the Nelson-Atkins Museum with Blake’s triumphant creation. The composer commented that this image appears to be filled with ‘so much joy, beauty, and depth’. He seems almost triumphant in his expression in this movement. The birds flutter and fly, and so does the music.

Adam Schoenberg: Picture Studies – X. Pigeons in Flight (Kansas City Symphony; Michael Stern, cond.)

Schoenberg’s work lacks the connector of Mussorgsky’s Promenade, but still works to move us from image to image, century to century. This is something more art museums should do – it’s a wonderful excursion around a century of art in one place, and the variety of media can lead visitors to new parts of a collection.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter