Sergey Akhunov’s Jazz Inspired by Henri Matisse

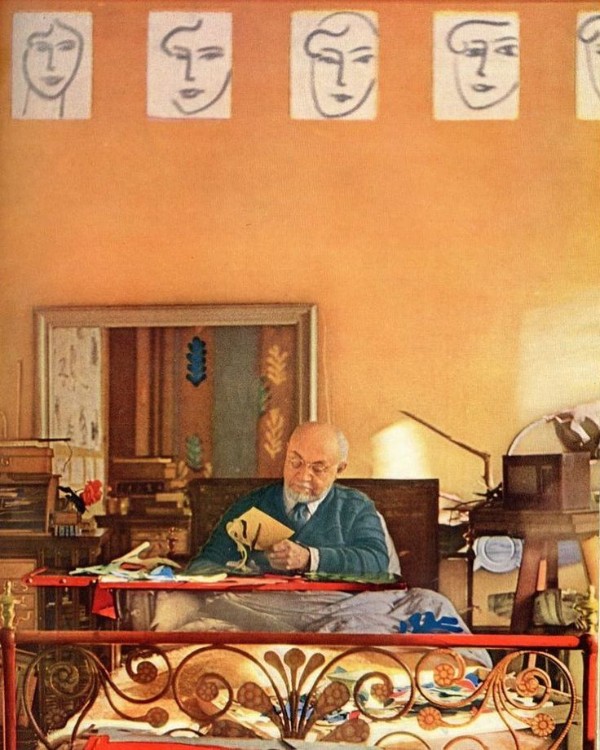

In 1941, Henri Matisse (1869–1954) had abdominal surgery and afterwards was confined to a bed or a chair. With his limited mobility, painting and sculpting were out of the question; however, he still had his hands and his ideas, and so he started work on a new medium. He cut out shapes from coloured paper or from paper he’d painted a certain colour and created colourful montages that he arranged as collages. His cut-outs were more than a child’s experiments: as an experienced artist, he brought an eye for colour and arrangement that tells its own story.

Matisse in Nice, 1941

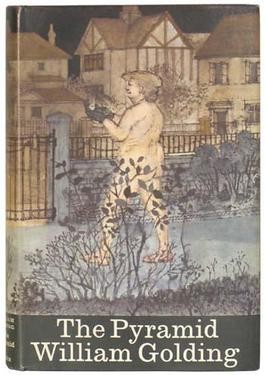

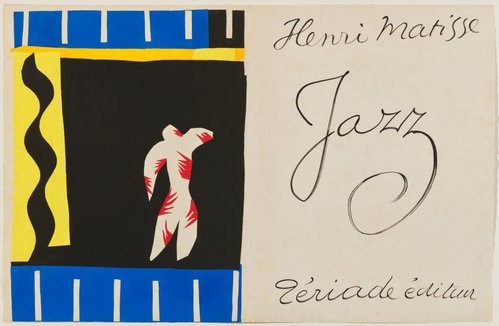

Originally intended to be covers for the magazine Verve, the publisher, Tériade, instead issued them as an artist’s portfolio.

Henri Matisse: Jazz, 1947, cover (Art Gallery NSW)

There were 20 colour prints, each about 41 by 66 cm (16 by 26 inches), and 70 pages of Matisse’s handwritten thoughts on the process. The paper was painted in gouache by his assistants before Matisse made his cutouts. The assistants then put the cutouts on the studio wall, arranging them under Matisse’s direction.

From these originals, stencils were made, printed with the same vivid colours used on the cutouts.

The original book was created in a limited edition of 250; it was very popular and was reprinted in 2001.

One book about this collection is entitled Drawing with Scissors, written by Oliver Beggruen and Max Hollein, and that title seems to be perfect for describing Matisse’s new art form. With his limited mobility, Matisse had found a way to solve ‘the problems of form and space, outline and colour’ in a way that satisfied the artist.

The title, Jazz, was developed by his publisher, and Matisse thought it was perfect for its connection with both art and musical improvisation. The word ‘jazz’ evokes thoughts of rhythm, repetition, musical structure, and musical breakdown of structure.

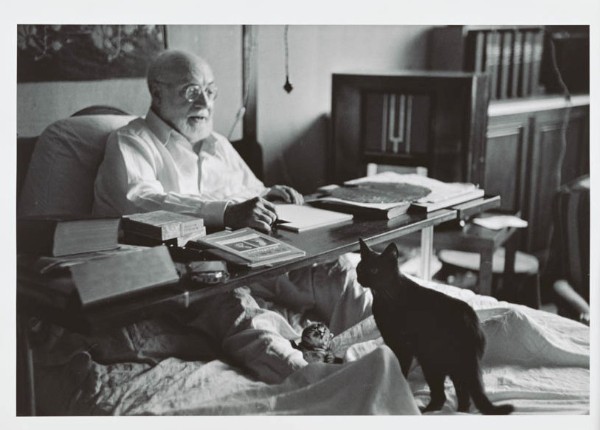

Matisse in bed with helping cat

The work is deeply rooted in memories of the circus, travel, and folktales. After the first 5 circus images, Matisse ranges much more widely. One commentator wrote that ‘despite the vivid colours and folkloric themes, few of the plates are actually cheerful. Several are among Matisse’s most ominous images.’ Art and artifice both have a place in this collection.

In 2013, the Ukrainian composer Sergey Akhunov (b. 1968) saw an exhibition of Matisse’s Jazz in Moscow.

Sergey Akhunov

The composer writes, ‘Looking at those works then, it occurred to me how interesting it would be to compose music that has nothing to do with jazz, and to call it “Jazz”, like his book of cut-outs. And the titles of Matisse’s works – L’Enterrement de Pierrot (Pierrot’s Funeral), Le Cheval, l’écuyère et le clown (The Horse, the Rider and the Clown), Le Cauchemar de l’éléphant blanc (The Nightmare of the White Elephant), La Chute d’Icare (The Fall of Icarus) – seemed to be begging a musical interpretation. How would it sound? What tools should be used? I had no idea, but I liked the concept.’

In the end, after a year of thought, Akhunov created a 15-part work for violin and piano. The violinist Julia Igonina and the pianist Maxim Emelyanychev commissioned him for a work, and he returned to his thoughts on Matisse and improvisation.

Matisse in bed, 1948

Akhunov states first what they are not: they are not an illustration of Matisse’s works; there are no analogies to be found between this music and the paper collages. The connection lies on a more subtle plane. We spoke above about the title Jazz coming from the publisher’s suggestion, and Matisse saw it as a title that recognised the improvisation in art that he liked so much in music.

Rather than thinking about how Akhunov reflects the image, think about how he conveys the idea behind the image. We won’t go through all 15 movements of Akhunov’s work, but just look at selected highlights.

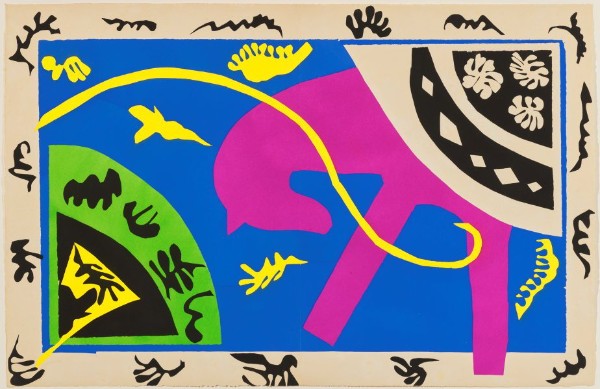

In The Horse, the Rider, and the Clown, Matisse doesn’t show the horse in motion, just its bow at the end of the performance. Only the edge of the Rider’s dress is visible in the top right part of the image. The clown is in the fan at the bottom left side. Everything is still.

Matisse: Jazz: The Horse, the Rider, and the Clown, p. V, 1947

Akhunov doesn’t start with that stillness; he starts 10 minutes before it, giving us the Horse in motion, the tension racking up as it goes faster and faster, and still the Rider stands proud and stable on its back. His improvisation on how we ended up in the final pose is our first idea of how the two artists’ improvisation might work together.

Sergey Akhunov: Jazz – No. 3. The Horse, the Rider and the Clown (Julia Igonina, violin; Maxim Emelyanychev, piano)

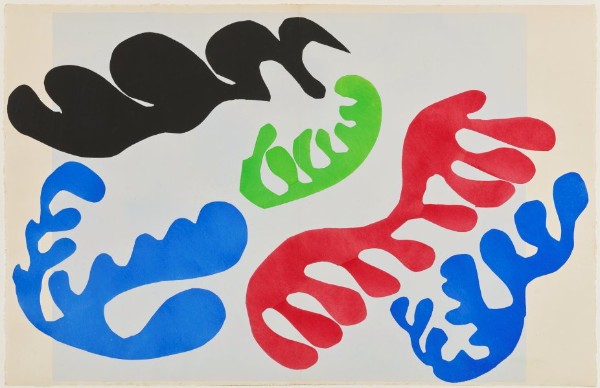

In Pierrot’s Funeral, everything has gone wrong for our prototypical clown. Instead of a stately procession, the horse-drawn hearse is in an uproar. The horse, with its magnificent headdress, is rearing, and the hearse has one up into the air, resting on only two wheels. Water splashes all around, and it can only be chaos.

Matisse: Jazz: Pierrot’s Funeral, p. X, 1947

Akhunov gives us the sombre background. All may be in chaos on the street, but the invisible mourners in the black background are sad and quiet at the loss of their poor Pierrot. Or perhaps we are the dead Pierrot. Throughout his life of turmoil and tumult, nothing has ever been as quiet as this hearse, no matter what’s going on outside.

Sergey Akhunov: Jazz – No. 5. Pierrot’s Funeral (Julia Igonina, violin; Maxim Emelyanychev, piano)

Akhunov frames his work with three Lagoon movements. These all appear at the end of Matisse’s book, but Akhunov places them as the first movement, the 7th movement, and as the last movement, No. 15.

These three images came from Matisse’s trip to Tahiti, which he made in 1930. These weren’t his only Tahiti-inspired works; they also included his 1935 A Window in Tahiti, depicting a sailboat moored under some trees, and his 1952–1953 cutout Memory of Oceania.

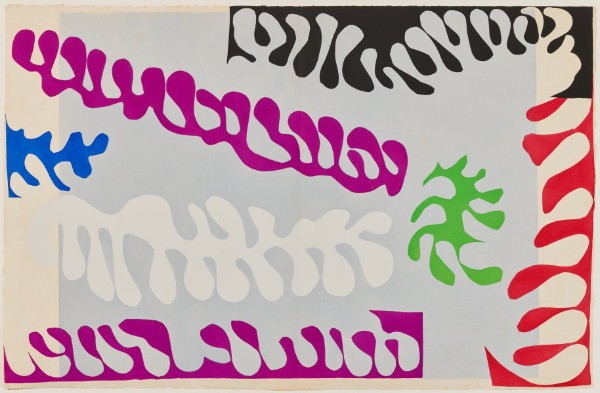

Matisse: Jazz: The Lagoon, p. XVII, 1947

Akhunov opens with a quiet dip into the waters – just a glimpse of the seaweed and other underwater life.

Sergey Akhunov: Jazz – No. 1. Lagoon I (Julia Igonina, violin; Maxim Emelyanychev, piano)

Matisse: Jazz: The Lagoon, p. XVIII, 1947

The music is more complex as the image becomes a reverse of the previous one. Instead of being defined by the space the fronds take out of the coloured edges, this frond floats alone in black, surrounded by invisible currents.

Sergey Akhunov: Jazz – No. 7. Lagoon II (Julia Igonina, violin; Maxim Emelyanychev, piano)

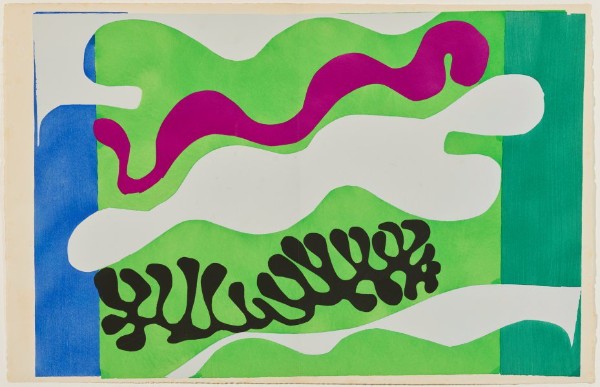

In the final Lagoon, the fronds float free.

Matisse: Jazz: The Lagoon, p. XIX, 1947

Sergey Akhunov: Jazz – No. 15. Lagoon III (Julia Igonina, violin; Maxim Emelyanychev, piano)

In the text that accompanies these three Lagoons, Matisse wrote, ‘Lagoons, aren’t you one of the seven wonders of the Paradise of painters?’

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter