Musical Interpretations of Henri Matisse’s La Tristesse du roi

When we think of self-portraits, we think of images of the artist at work, canvas in front of him, brushes in hand, done at a strange angle so the artist could paint and look in a mirror at the same time.

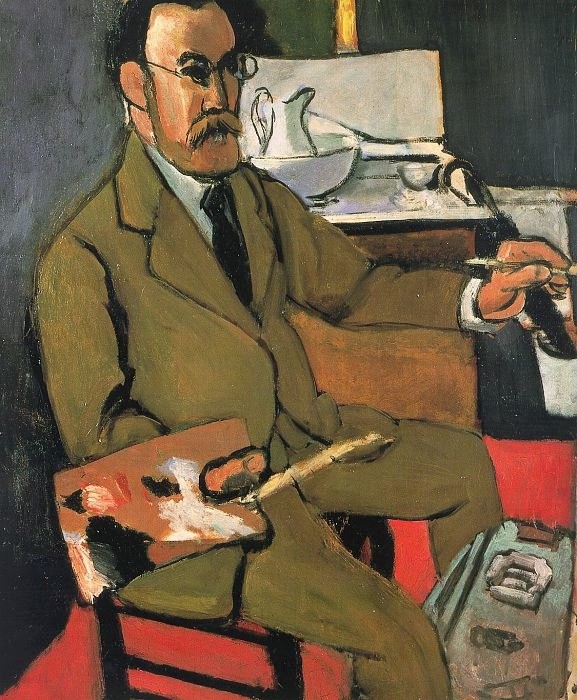

With Henri Matisse (1869–1954), we have one like that, his self-portrait done in 1918:

Matisse: Self-portrait, 1918 (Matisse Museum)

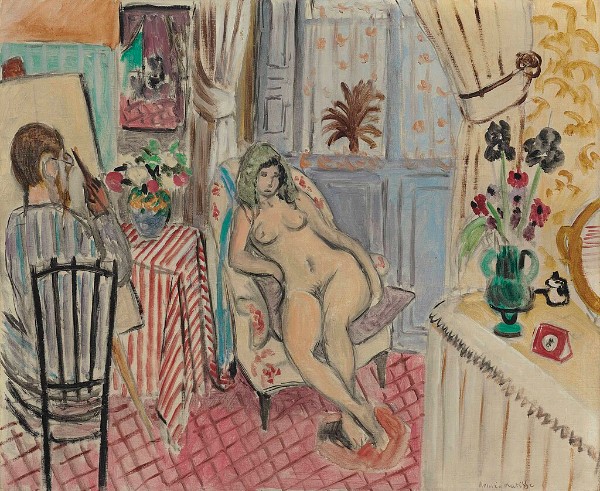

But we also have ones where the artist is less prominent, such as his self-portrait of himself at work in 1921.

Matisse: L’artiste et le modèle nu, 1921

In 1952, however, he did a more unusual self-portrait in his paper cut-outs style. Entitled La Tristesse du roi (Sorrows of the king), the work is based on a reference to a painting by Rembrandt. Although it’s supposed to be based on David Playing the Harp in front of Saul, was painted ca. 1630 – 1631, the format seems more like the later painting of Saul and David. From the Bible, in 1 Samuel, we have the story of David playing his harp to appease the torments of King Saul (1 Sam. 16:23)

Rembrandt: David Playing the Harp in front of Saul, 1630–1631 (Städel Museum)

In a shadow on the right side, David plays his harp for Saul, who wears his crown, has a magnificent gold necklace, and clutches his staff. He only looks at David with a side-eye, otherwise turning his head to face the viewer. He bears an introspective look.

Rembrandt: Saul and David, 1650–1670 (The Hague: Mauritshuis)

In Saul and David, the seated Saul holds his head in his hand, which is holding a curtain. His agitation is visible even as he holds his symbols of state: his crown and his staff. To his left, at the bottom right corner of the image, David plays his harp, seeking to solace the king. From the Bible, in 1 Samuel, we have the story of David playing his harp to appease the torments of King Saul (1 Sam. 16:23)

What of Matisse’s work?

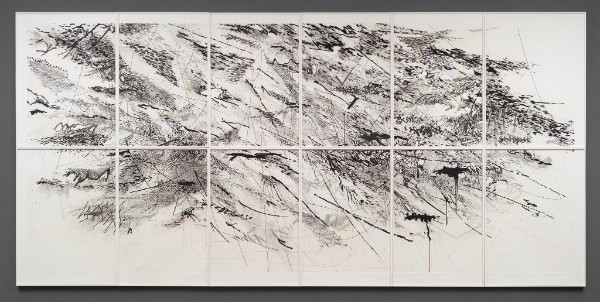

Matisse: La tristesse du roi, 1952 (Centre Pompidou)

In this image, Matisse depicts himself as the black form in the centre of the image, and is ‘surrounded by the pleasures which have enriched his life: the yellow petals fluttering away have the gaiety of musical notation; the green odalisque symbolises the Orient, while a dancer pays homage to the female body’. It’s the theme of old age and remembrance, music soothing the ills of the world, and the self as the centre of the world.

British composer Peter Seabourne (b.1960) wrote a septet based on this cut-out, entitled The Sadness of the King (2001, rev. 2004). The ensemble, consisting of clarinet, bassoon, horn, violin I and II, viola, and piano, paints in sound the troubles of the king. Distracted lines come in and out, each catching our attention for a flash before something else whisks away our attention. By the end, though, calm has returned, and the voices work together on a single theme.

Peter Seabourne (photo by Evgeniadocker)

Peter Seabourne : The Sadness of the King (2010)

In 2008, as part of his piano work White Book 2, British composer Graham Lynch made one movement, The Sadness of the King. Focusing on the introspection of the king, Lynch uses a tango rhythm, slowed down and played quietly, to depict his inner turmoil. A melodic line ‘searches its way through the music’.

Graham Lynch (photo by Simon Green)

Graham Lynch: White Book 2 – V. The Sadness of the King (Mark Tanner, piano)

Where Matisse, as the black centre of his cut-out, seems to be a black hole of unhappiness, the light and motion in the world around him might give him an opportunity to emerge. His white hands emerging from the blackness and the flowers that lighten his darkness speak to a future happiness.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

What a fascinating exploration of the links between the interpretations of the sadness of the king in

imagery and music.