Inspirations Behind Edward Gregson’s 3 Matisse Impressions

In his 1997 updating of his 1993 work for recorder and piano, British composer Edward Gregson (b. 1945) expanded performing forces to recorder and chamber orchestra. In his Three Matisse Impressions, Gregson gives us his impressions of one of the most varied of the late Impressionists by looking at three famous Matisse works.

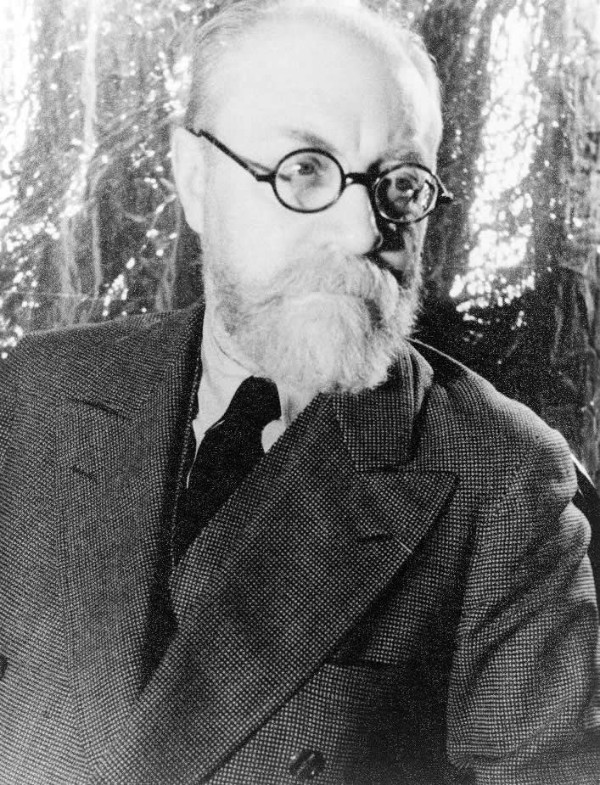

French artist Henri Matisse (1869–1954) worked in the fields of printmaking, sculpture, but is primarily known as a painter. He, along with Picasso, created the new artistic world of the 20th century. At the turn of the 20th century, his post-Impressionist style of Fauvism (Fauve meaning “wild beast”), which abandoned the representational images and realism of Impressionism for an emphasis on strong colour.

Carl van Vechten: Henri Matisse, 1933 (Library of Congress)

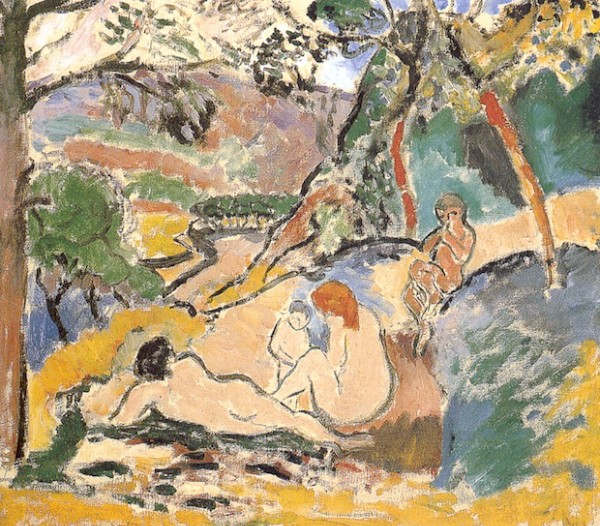

Matisse created his Fauve painting Pastorale in 1905 in Collioure, in the Pyrénées-Orientales. Four nudes (two women, one child, and a man who is playing a recorder) relax in a wooded landscape. The use of non-naturalistic colour comes to the fore, as do Matisse’s relaxed body postures. The use of colour represents not reality but the artist’s emotional reaction to the scene. The emphasis on blues and greens, as well as yellows and browns, gives us a warm, sunlit feel. The foliage in the trees seems to suggest movement, and the road at the bottom of the hill, moving through the trees, shows the way forward.

Henri Matisse: Pastoral, 1905 (Paris: Musée d’Art Moderne; stolen 2010)

Gregson employs the pastoral through his use of non-modern scales, tying the three works together by devising his melodies around the rise and fall of a perfect fifth. He bases this movement on the Lydian mode, which starts with a basic C major scale, then raises the fourth pitch by a half-step. The change of place of the half step intensifies the C major.

Edward Gregson: 3 Matisse Impressions (arr. for recorder, strings, harp and percussion) – I. Pastoral (John Turner, recorder; Royal Ballet Sinfonia; Edward Gregson, cond.)

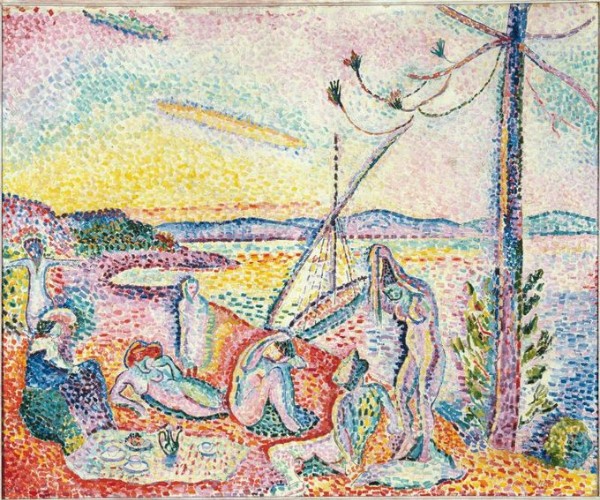

Matisse’s 1903 work, Luxe, calme et volupte, is in another post-Impressionist style known as Divisionism. This predates his work in Fauvism. Divisionism was a style developed by Paul Signac where individual dots of colour placed on the painting, when viewed at a distance, blend and create the image. By juxtaposing dots or patches of different colours, the artist created a situation where the colours would blend in the viewer’s perception and ‘mix in the eye’.

Luxe, calme et volupte was one of Matisse’s most important works in Divisionist style. It’s related to his later Fauvist works in that forms are simplified, and the images may come directly from the artist’s imagination.

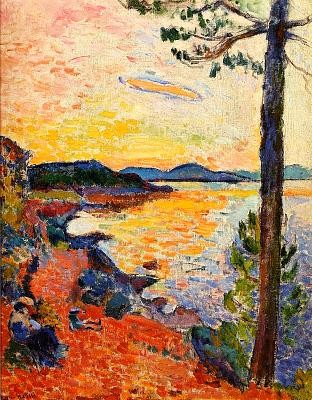

Matisse had gone down to Saint-Tropez to spend the summer with Paul Signac, bringing his wife Amélie and his youngest son, Pierre.

His first attempt was Le Goûter (Tea Time). We have Amélie seated in street clothes and little Pierre to her right. A pine tree oversees the scene.

Matisse: Le goûter, golfe de Saint-Tropez, 1904

(Düsseldorf: Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen)

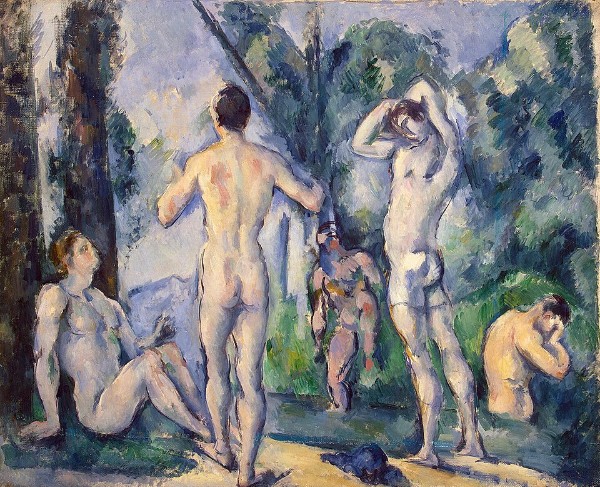

Then, combining that image with an idea from an earlier work by Cezanne portraying bathers, which was in Matisse’s studio. Cézanne created many pictures of bathers, experimenting with faces, light on bodies, and light and shade, as seen in this bather’s picture held in the Hermitage.

Cézanne: Les Baigneurs (The Bathers), ca 1890–18991 (St Petersburg: Hermitage Museum)

When the two ideas were joined, we now have Amélie, at the left, still in her street clothes and little Pierre standing, and a group of nudes in different poses. The tree has become fantastical, keeping its lower foliage, but having its upper branches become wild curves with fluffs of colour at the ends. The long yellow cloud remains, but the shoreline has become simplified, and a boat is now moored along the shore.

His title comes from Baudelaire’s collection Les Fleurs du Mal, and the poem Invitation au voyage:

| Là, tout n’est qu’ordre et beauté, | There, all is order and beauty, |

| Luxe, calme et volupté. | Luxury, peace, and pleasure |

This was Matisse’s vision of the world of leisure and also his vision of a more relaxed style of painting. For him, the golden age could be created through melding the fleeting impressions of now with the permanence of the past. The sailboat is the exotic addition, symbolising the ability to flee the present.

Henri Matisse: Luxe, Calme et Volupté, 1903 (Paris: Centre Pompidou)

Opening with a harp arpeggio, Gregson’s second movement takes us out of the worries of the world. The composer tried to write his music in the same Impressionistic mode as his artist: rhythm is undefined and imprecise, just as in Matisse’s points of colour. It is the juxtaposition of rhythm in the various voices that gives us our work. He also takes a technique from Russian music of the time by using an octatonic scale that alternates whole and half steps. The octatonic scale was so used by the composers around Rimsky-Korsakov that it was sometimes called the Korsakovian scale, and Stravinsky was one of its users. Just like Matisse, Gregson wants us to stand back and discover the larger waltz hidden among the dots.

Edward Gregson: 3 Matisse Impressions (arr. for recorder, strings, harp and percussion) – II. Luxe, calme et volupte (John Turner, recorder; Royal Ballet Sinfonia; Edward Gregson, cond.)

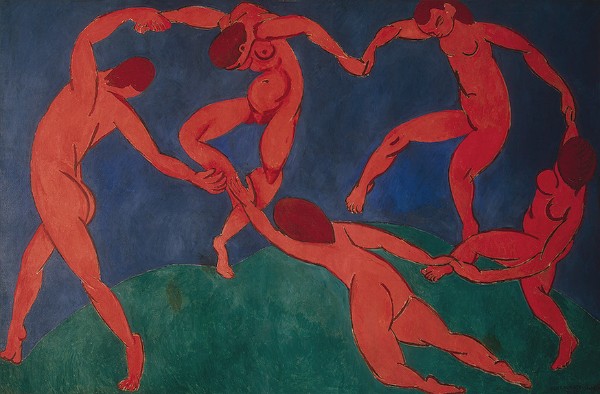

One of Matisse’s most famous works, dating from 1910, is simply called La Danse. Using three highly contrasting colours, red for the dancers, blue for the sky, and green for the grass, Matisse creates a primitive celebratory ensemble. Heads down in concentration, their feet flying in the air, the dancers arch and whirl.

Henri Matisse: La Danse, 1910 (St Petersburg: The Hermitage)

Gregson picks up on the implied speed of the dance and creates his own fast and rhythmic vision. The dancing recorder sets the pace, with the strings becoming an almost literal ground below it.

Edward Gregson: 3 Matisse Impressions (arr. for recorder, strings, harp and percussion) – III. La Danse (John Turner, recorder; Royal Ballet Sinfonia; Edward Gregson, cond.)

Matisse was a non-representational painter in these works – the people are less important than the scene and the emotion of the scene. In Pastorale, we are sprawling in the shade, amused by the sound of a recorder. In Luxe, Calme, and Volupté, we are down from the mountains and at the seaside, recovering from a dip in the water and dreaming of future travels. In La Danse, the world has gone away entirely, and we are solely in the concentrated world of the dancers. In the same way, Gregson takes us from the countryside to the beach to a world that is pure movement.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter