The medium of the Prelude has been used by composers for a number of different vehicles. At first, they were literally the music that came before, i.e., preceded another piece. The first one dates from 1448. Then, they were used in the Renaissance as finger warmup pieces to get instruments ready to play. Couperin used them in the 17th century as introductions to his harpsichord suites, where the pieces were without barlines and with the note duration left to the performer. In Germany, Johann Pachelbel and later, J.S. Bach formalised them and paired them with fugues, and did them in all keys.

Jump ahead a few centuries, and we have the Greek-Cypriot composer Constantinos Y. Stylianou (b. 1972) using the prelude as a vehicle for the history of art from the votive monument of The Winged Victory of Samothrace to 20th-century monuments of a different medium.

Commissioned in 2008 for concerts held to mark the French Presidency of the EU, Stylianou wrote two preludes, inspired by Debussy’s two books of preludes. Inspired by his beginning, Stylianou continued to write preludes for the next decade, eventually creating his cycle of 12 works. Final revisions to the collection were made in 2018.

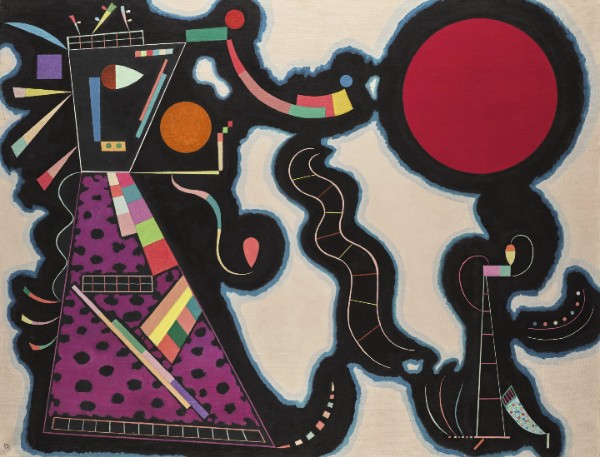

Stylianou explores the wide world of art: Mondrian’s Composition with Blue and Yellow (1932); Cézanne’s L’étang des sœurs (1875); Turner’s Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth (1842); Campin’s The Weeping Angel from the Seilern Triptych (c. 1410/15); Die Lebensstufen (1835) by Caspar David Friedrich; L’homme qui marche (1947) by Alberto Giacometti; Matisse’s La leçon de piano (1916); Klimt’s The Kiss (1907/08); Kandinsky’s Le rond rouge (1939); O kósmos tis Kíprou (1967/72) by Adamantios Diamantis; and finally The Dance (1988) by Paula Rego.

Some are works that capture an image, and others are works that capture a historical moment. In each case, Stylianou gives each prelude a unique character that leads the listener to reflect on the work being delineated.

Winged Victory of Samothrace, a triumphant statue of the goddess Niké created on the island of Samothrace at the beginning of the 2nd century BC (ca 190 BC), is where he starts. Discovered in 1863, the statue stands at the top of the main staircase at the Louvre, Paris.

The Winged Victory of Samothrace, ca 190 BC (Paris: Louvre)

Stylianou starts with small themes that gradually build until, at last, our goddess takes flight.

Constantinos Y. Stylianou: 12 Preludes, Book 1 – No. 1. I Níki tis Samothrákis (Nicolas Constantinou, piano)

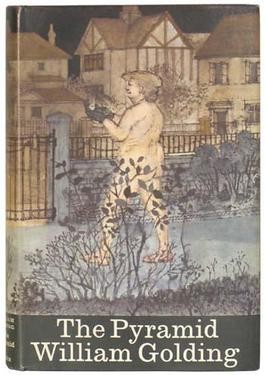

Next, we jump to the Netherlands and the style of Neoplasticism. Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) developed his abstract style by simplifying his images until they were reduced to lines on a page. Spaces are defined by black lines and, by limiting his colours to the three primary shades of red, blue, and yellow, the three primary values of white, black, and grey, and two directions, horizontal and vertical, Mondrian created a unique vision of the world.

In Composition with Blue and Yellow of 1932, Mondrian has a work where ‘bisecting lines cross the entire composition in the upper-right region, and a shorter but wider black bar subdivides the right-hand vertical margin. The resulting irregular grid creates five planes—two of colour and three in white—whose sizes, proportions, and shapes are never repeated but still balanced.’

Piet Mondrian: Composition with Blue and Yellow, 1932 (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Stylianou sets up his basic pattern in the bass with repeating notes that set up our musical version of the defining black lines, while the right hand adds the colour.

Constantinos Y. Stylianou: 12 Preludes, Book 1 – No. 2. Composition with Yellow and Blue (Piet Mondrian) (Nicolas Constantinou, piano)

From 1932, we go back to 1875 and Paul Cézanne (1839–1906). This Post-Impressionist painter gives us a world of green in his vision of a footpath at the side of a pond. Cézanne was visiting his friend Camille Pissarro in the village of Osny, north of Paris. The paint was thickly applied with a palette knife, resulting in a dynamic painting that captures not only the stillness of the path but the life in the surrounding forest. The light path and the light tree trunks pull our vision deeper into the image. We see the water and the clearing in the trees, and only later come back to look at the shadowed foreground.

Paul Cézanne: L’étang des sœurs, 1875 (London: Courtauld Institute of Art)

Now we’re in a quiet wood, near a still pond, with the complexities of light and shadow bringing highlights to the scene.

Constantinos Y. Stylianou: 12 Preludes, Book 1 – No. 3. L’étang des sœurs (Paul Cézanne) (Nicolas Constantinou, piano)

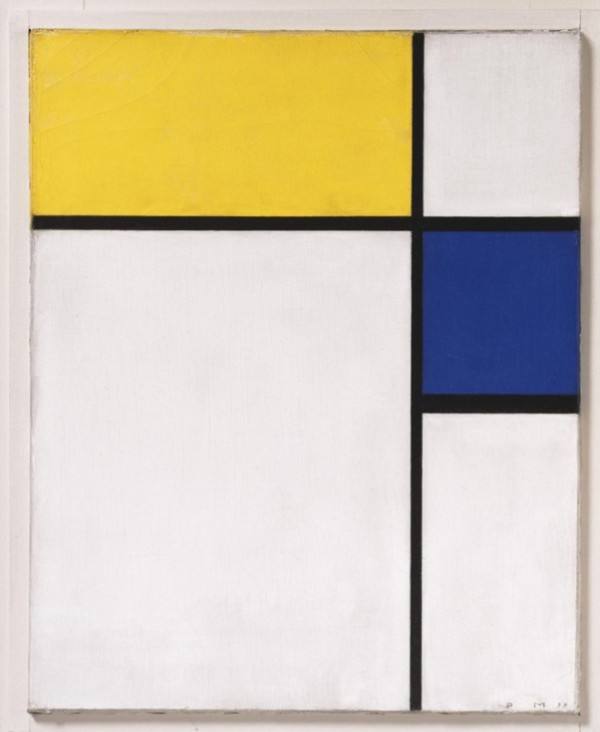

Caught in a storm at sea as his boat was leaving the port of Harwich, the 67-year-old J.M.W. Turner had the sailors lash him to the mast so he could observe nature in the raw. In a swirl of mist and water, cloud and foam, the paddle steamer Ariel fights its way through a snowstorm. Although critics at the time didn’t see its value, the English art critic John Ruskin called it “one of the very grandest statements of sea-motion, mist and light, that has ever been put on canvas.”

J. M. W. Turner: Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth, 1842 (Tate Gallery)

With a dramatic opening of arpeggios, Stylianou captures the rolling of the waves and the boat’s motion through the turbulent water. Around it, the snowstorm blows, and the light brightens and fades as the clouds violently move.

Constantinos Y. Stylianou: 12 Preludes, Book 1 – No. 4. Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth (J. M. W. Turner) (Nicolas Constantinou, piano)

Behind the figure of the dead Christ being laid in his tomb

Robert Campin: The Seilern Triptych, ca 1410–1415 or 1420–1425) (London: Courtauld Institute Gallery)

And an angel uses a very human gesture to wipe a tear away.

Robert Campin: The Weeping Angel (detail) from The Seilern Triptych, ca 1410–1415 or 1420–1425)

(London: Courtauld Institute Gallery)

Robert Campin (ca 1375–1444) created the triptych, which is also known as Entombment, for an unknown location. Its small size suggests that it was for private devotion, rather than for a large church.

Stylianou’s Prelude focuses on falling melodic lines and falling melodic tears. Against a sombre background, our solitary angel does what no one else in the picture can do: give a visual sign of the sadness that engulfs everyone.

Constantinos Y. Stylianou: 12 Preludes, Book 1 – No. 5. The Weeping Angel from The Seilern Triptych (Robert Campin) (Nicolas Constantinou, piano)

In an uncharacteristically flat-land setting, German artist Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840) gives us a meditation on life and mortality. Set in Utkiek, northern Germany, where Friedrich was born, the foreground shows us an aged man walking towards a young family. The old man is a self-portrait of Friedrich, shown walking toward his top-hatted nephew John Heinrich. The small boy and girl are Friedrich’s son Gustav Adolf, his daughter Agnes Adelheid, and the older girl his daughter Emma.

In the background, we have three sailing ships and, in front of them, two small sailboats. To extend the family allegory, the two small sailboats are the children, the central boat is the aged father returning to port for the last time, and the two background ships represent the voyage of man to explore.

Caspar David Friedrich: Die Lebensstufen (The Stages of Life), 1835 (Leipzig Museum der bildenden Künste)

Caspar David Friedrich probably did not title the painting as we know it today, as he avoided descriptive titles, and it was probably given the name Die Lebensstufen during the late-19th-century revival of interest in his work.

The music begins with a simple, child-like melody that becomes more complex and complicated, with additional decoration and more important statements as we work our way through life. The quiet and slower ending brings us back to the simplicity of life.

Constantinos Y. Stylianou: 12 Preludes, Book 1 – No. 6. Die Lebensstufen (Caspar David Friedrich) (Nicolas Constantinou, piano)

Swiss artist Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966) is best known for his elongated figures of tall, thin human figures, made between 1945 and 1960. The existential nature of his work was defined by its Guggenheim label: ‘The precariousness of the figure relates to the limits within which every human being has to live in a society subject to multiple conflicts and challenges, and to both natural and man-made disasters. The face is barely defined, the intention being to capture the generality of the human species and so enhance the universal character of what is represented by the piece, arousing a greater sense of identification in every viewer.’

Created from a single piece of bronze, the human figure is drawn out and elongated into an elemental form. Caught in the middle of a step, the body is bent forward to move the weight onto the front leg.

Alberto Giacometti: L’homme qui marche I, 1960 (Bilbao: Guggenheim Bilbao)

The walking man starts out with single steps, on repeated notes, before advancing.

Constantinos Y. Stylianou: 12 Preludes, Book 1 – No. 7. L’homme qui marche (Alberto Giacometti) (Nicolas Constantinou, piano)

Created in late summer 1916, The Piano Lesson by Henri Matisse (1869–1954) is set in Matisse’ living room with his son, Pierre, at the piano. On the piano is the familiar pyramid of a metronome and a burning candle. At the front left is Decorative Figure, made by Matisse in 1908, and behind the boy is the painting Woman on a High Stool from 1914.

Although his initial drawing was quite naturalistic, Matisse worked and reworked the image to remove detail and to capture that moment in time when light (in green) brightens the darkened interior (shown by the need for a candle).

Matisse: The Piano Lesson, 1916 (New York: Moma)

Stylianou recreates the repetitive nature of a piano lesson with the repeated bass notes under a moving melodic line.

Constantinos Y. Stylianou: 12 Preludes, Book 1 – No. 8. La leçon de piano (Henri Matisse) (Nicolas Constantinou, piano)

Austrian painter Gustav Klimt (1862–1918) created some of the most familiar paintings of the Vienna Secession movement. Art Nouveau style came to life in his hands. Painted in oils, but with overlaid gold, silver, and platinum leaf, The Kiss is one of Klimt’s most famous works. Its exhibition in 1908 brought together elements of the older Arts and Crafts movement in its use of organic forms, and the new Art Nouveau style in the decoration of the figures’ robes.

The couple are caught in an intimate embrace. By use of a flat background, Klimt is cutting his ties with the Impressionists, who showed landscape details; the only suggestion of place in the painting is at the base, where a flowery meadow seems to trail upward into the material behind the couple.

Gustav Klimt: The Kiss (Der Kuß), 1907–1908 (Vienna: Belvedere)

The ecstasy of the couple’s embrace is very much a part of the musical imagery. It seems to whirl about, carrying us from the meadow to the stars.

Constantinos Y. Stylianou: 12 Preludes, Book 1 – No. 9. Der Kuss (Gustav Klimt) (Nicolas Constantinou, piano)

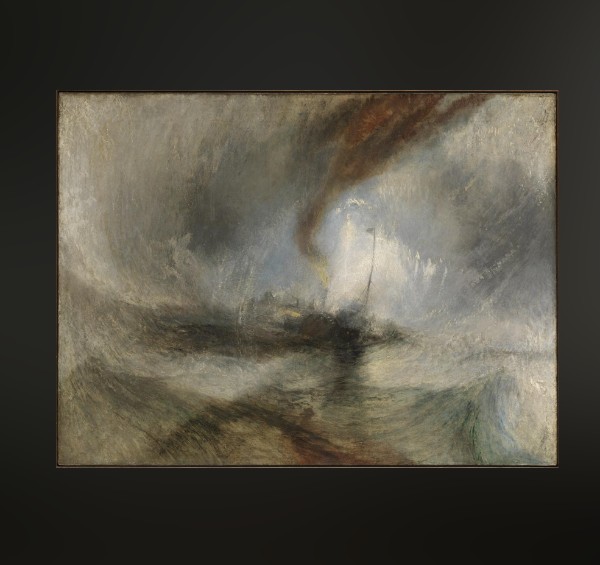

Created in Paris in 1939, Le Rond rouge (The Red Circle) is one of Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky’s (1866–1944) purely abstract works. It’s an ‘exquisite arrangement’ in the surrealist style, but doesn’t depict any particular object. One critic saw it as a representation of the interior of the body, but one that devolved into a panoramic landscape. A geometry of form is as important as the pathways and evocative imagery of the curved lines. The red circle seems to be the point where all pathways lead.

Wassily Kandinsky: Le Rond rouge, 1939

Climbing and travelling lines take us through the paths of the picture.

Constantinos Y. Stylianou: 12 Preludes, Book 1 – No. 10. Le rond rouge (Wassily Kandinsky) (Nicolas Constantinou, piano)

Cypriot painter Adamantios Diamantis (1900–1994) studied in London before returning to teach at the Pancyprian Gymnasium of Nicosia from 1926 to 1962. He is considered to be the father of Cypriot art.

His most important work is the panoramic painting, Ο κόσμος της Κύπρου (The World of Cyprus), which he created between 1967 and 1972. At 17.50 meters long and 1.75 meters high (37.75 x 5.7 feet), the painting started with portraits he did of the everyday people of Cyprus. His hundreds of drawings, first exhibited in 1957, formed the basis for this work. His idea was to create a work that would capture the whole world of Cyprus. In the final painting, some 67 figures appear, posed against a background landscape. The figures come from the 30 regions and villages of the island. The figures are done in black and white to reflect Cypriot clothing, but the foreground is done in ochre, unifying the work.

Adamantios Diamantis: Ο κόσμος της Κύπρου (The World of Cyprus) (Cypriot Collection)

Adamantios Diamantis: Ο κόσμος της Κύπρου (The World of Cyprus) (Left detail) (Cypriot Collection)

Adamantios Diamantis: Ο κόσμος της Κύπρου (The World of Cyprus) (Centre detail) (Cypriot Collection)

Diamantis’ painting is given a prelude that emphasises each figure’s importance in its own world. Some are busy, some are self-important, and others make important statements of great gravity.

Constantinos Y. Stylianou: 12 Preludes, Book 1 – No. 11. O kósmos tis Kíprou (Adamántios Diamantís) (Nicolas Constantinou, piano)

Portuguese artist Paula Rego (1935–2022) worked in a style that moved from abstract to representational. Growing up in Portugal under the care of her grandmother, Rego absorbed many of the older generation’s stories and folktales. These would be important elements in her artworks. She studied art at the Slade School of Fine Art and became part of The London Group, joining David Hockney and Frank Auerbach as a member.

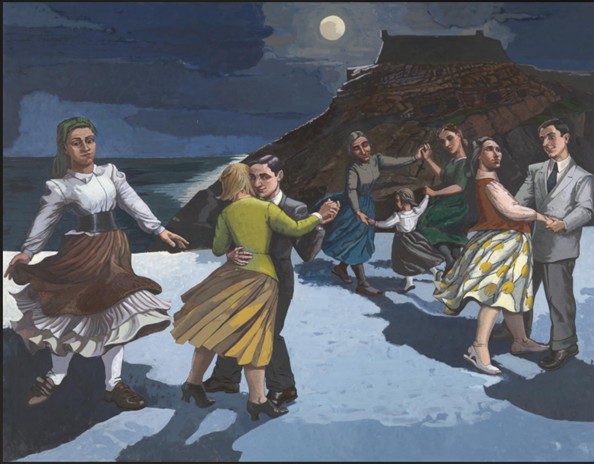

The Dance captures elements of her early life in Portugal with her grandmother. The image could be of a fiesta or an allegory on the dance of life – from the child through youth, young love, a mature couple, to the widow.

Paula Rego: The Dance, 1988 (Tate Gallery)

Stylianou also takes us through a dance of life, from simple repetitive motions through more complex dances and steps. At the very end, we whirl off into space.

Constantinos Y. Stylianou: 12 Preludes, Book 1 – No. 12. The Dance (Paula Rego) (Nicolas Constantinou, piano)

In his survey of art from ancient Greece to the 20th century, Stylianou has used the old-fashioned idea of the prelude to create his own artistic world. Each individual work of art has its own individual prelude and sound. It’s like having a pocket museum in your piano!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter