Throughout music history, music critics have often elevated (or eviscerated) a composer’s reputation.

Sometimes critics and composers have found themselves in public feuds. Other times, the composer and critic in question became unlikely friends.

Today, we’re looking at four of the most influential composer-critic relationships in classical music history.

Hector Berlioz and François-Joseph Fétis

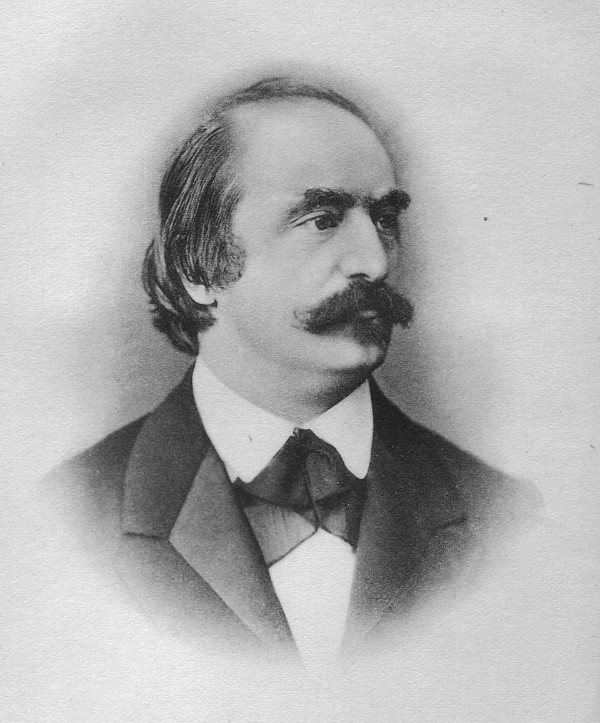

François-Joseph Fétis

Fétis was born in present-day Belgium in 1784, the son of an organist and the grandson of an organ builder.

He began composing at seven and working as a professional organist at nine. At sixteen, he left for Paris to study music at the Conservatoire. He became a professor there himself in 1821.

In 1827, he founded a journal named the Revue musicale, the first French publication devoted solely to music. He became well-known as a critic, teacher, and music theorist.

Portrait of Hector Berlioz

Berlioz wasn’t a fan of Fétis’s tastes. He poked at him in one of the monologues in Lélio, an 1832 work for narrator, chorus, and orchestra, portraying Fétis and his ilk as fuddy-duddy musical conservatives:

“These young theorists of eighty, living in the midst of a sea of prejudices and persuaded that the world ends with the shores of their island; these old libertines of every age who demand that music caress and amuse them, never admitting that the chaste muse could have a more noble mission; especially these desecrators who dare lay hands on original works, subjecting them to horrible mutilations that they call corrections and perfections, which, they say, require considerable taste. Curses on them! They make a mockery of art!”

Berlioz’s Lélio

In February 1835, Fétis shot back about Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique:

“I saw that melody was antipathetic to him, that he only had a faint notion of rhythm; that his harmony, formed by an often monstrous accretion of notes, was nevertheless flat and monotonous; in a word I saw that he lacked melodic and harmonic ideas, and I judged that he would always write in a barbarous manner; but I saw that he had the instinct for instrumentation, and I thought that he could fulfil a useful vocation in discovering certain combinations that others would put to better use than he.”

He also commented dryly in his 1845 treatise La musique mise à la porte de tout le monde:

“‘Fantastique’ music is composed of instrumental effects with no melodic line and incorrect harmony.”

Takeaway: Their feud typified a larger battle between Romantic Era innovation and Classical Era tradition in early nineteenth century Europe.

Johannes Brahms and Eduard Hanslick

Eduard Hanslick

Eduard Hanslick was born in Prague in 1825, the son of a piano teacher and a student. He began learning music as a boy.

At eighteen, he continued his music education in Prague while also earning a law degree. He began writing about music for small newspapers until he secured a position at the Vienna-based newspaper Neue Freie Presse, where he spent the rest of his career.

Writer Stefan Zweig described the Neue Freie Presse like this:

“…To the entire Viennese bourgeoisie, important works were those that won praise in the Neue Freie Presse, and works ignored or condemned there didn’t matter.”

As Zweig’s characterisation suggests, Hanslick valued composers who he felt worked in the tradition of established Viennese giants like Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert.

From the mid-century on, that meant supporting Robert Schumann and Johannes Brahms.

Hanslick became a friend of Brahms’s and even heard some of his new music in private before the public did.

Brahms’s Waltzes, Op. 39

In fact, Brahms dedicated his Waltzes, Op. 39, to Hanslick.

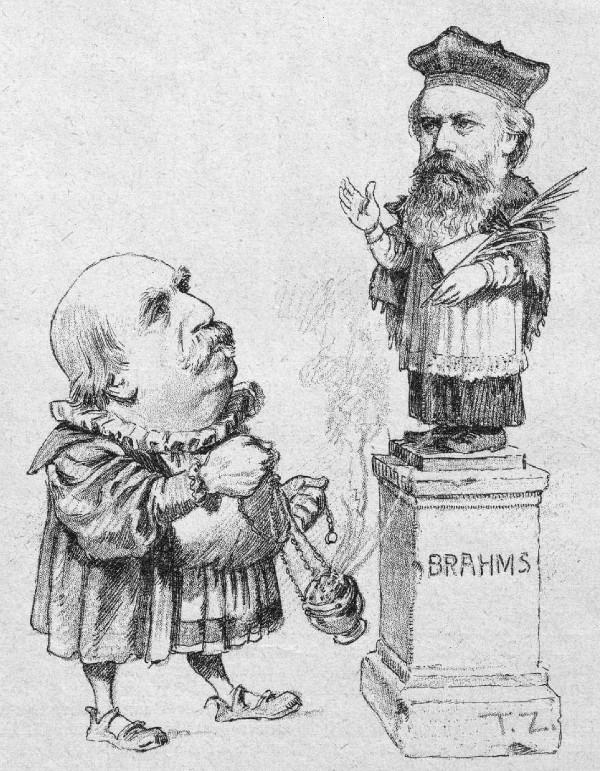

The Brahms/Hanslick friendship led to satirical cartoons portraying Hanslick worshipping Brahms as a god (even though in reality, his praise of Brahms was usually relatively measured).

Hanslick worshipping Brahms as a god

Hanslick wrote in 1862:

“Brahms is already a significant personality, possibly the most interesting among our contemporary composers… His music and Schumann’s have in common, above all else, continence and inner nobility. There is no seeking after applause in Brahms’ music, no narcissistic affectation. Everything is sincere and truthful.”

For his part, Brahms wrote to Clara Schumann:

“I knew a few persons for whom I feel as deep an affection as I do for [Hanslick]. To be so naturally good, well-intentioned, honest, truly modest, and everything else I know him to be seems to me very fine and very rare.”

Takeaway: Eduard Hanslick was an important backer of Brahms in the Viennese press and a main figure in the War of the Romantics. He championed Brahms as the heir to the tradition of absolute music post-Beethoven.

Richard Wagner and Eduard Hanslick

Richard Wagner, 1860

Eduard Hanslick is also remembered for his reviews of Wagner’s music. He initially was intrigued by it, but post-Lohengrin, his enthusiasm cooled.

Wagner’s Prelude to Lohengrin

Wagner punched back in his infamous “Jewishness in Music” essay, accusing Hanslick of having a ” gracefully concealed Jewish origin” and of being un-German. (Hanslick’s mother came from a Jewish family.)

Hanslick preferred Brahms’s embrace of absolute music, i.e., music that wasn’t married to a narrative or larger work of art. He understood Wagner’s talent, but Wagner’s megalomania, combined with his extramusical ideas, repelled him.

He wrote:

“I know very well that Wagner is the greatest living opera composer and the only one in Germany worth talking about in a historical sense. But between this admission and the repulsive idolatry which has grown up in connection with Wagner and which he has encouraged, there is an infinite chasm.”

Takeaway: This feud epitomised the clash between Wagner’s ideas and ideals and Hanslick’s preference for tradition and absolute music. It also foreshadowed how Wagner’s work would become the soundtrack to German nationalist movements during the 1930s.

Maurice Ravel, Claude Debussy, and Pierre Lalo

Pierre Lalo

Pierre Lalo was born in 1866, the son of composer Edouard Lalo. As a young man, he studied at the École polytechnique in Paris.

In 1896, he began writing for the Journal des débats. Two years later, he became the music critic for Le Temps, the most important newspaper in Paris: a promotion that made him a very influential figure in the French music scene.

In the 1890s, people often compared the music of Maurice Ravel and Claude Debussy (just as they do today). One of the people who noted their similarities was Pierre Lalo.

Ravel’s Shéhérazade

In 1897, Ravel conducted his Shéhérazade. Lalo wrote in a review of the performance that Ravel showed talent, but owed a creative debt to Debussy.

Ravel bristled against this idea. He felt strongly about not being lumped together with Debussy, writing:

“For Debussy, the musician and the man, I have had profound admiration, but by nature I am different from Debussy… I think I have always personally followed a direction opposed to that of symbolism.”

Ravel also wrote in a private letter to Lalo that Debussy’s work Pour le piano “from a purely pianistic point of view…represented nothing truly new.”

In 1907, Lalo published that comment in one of his columns, without asking Ravel’s permission. Understandably, seeing the comment out of context, Debussy took offence.

Between that and Debussy’s shocking abandonment of his wife in 1904, the personal relationship between the two composers became frigid.

Debussy’s Pour le piano

Even as Ravel matured as a composer, as late as 1911, Lalo wrote that “Where M. Debussy is all sensitivity, M. Ravel is all insensitivity, borrowing without hesitation not only the technique but the sensitivity of other people.”

Takeaway: Critic Pierre Lalo poked at Maurice Ravel in the press while also establishing a connection in the mind of music lovers between his and Debussy’s music. Simultaneously, he pushed them apart as colleagues and people.

Conclusion

From Hector Berlioz and François-Joseph Fétis’s scathing back-and-forths, to Eduard Hanslick’s dual role as Johannes Brahms’s ally and Richard Wagner’s adversary, to Maurice Ravel and Pierre Lalo’s prickly relationship…all of these stories demonstrate how critics of the past were intimately involved with the output of the most famous classical composers.

The legacies of these relationships still echo with us, modern listeners today.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter