Few years in classical music history capture a moment of transition as vividly as 1926.

That year, late-Romantic giants took their final bows; modernist voices sharpened their edge; early-music traditions resurfaced after generations; and musicians across continents experimented boldly with jazz, popular idioms, and new national identities.

Today, to celebrate the centenary of 1926, we’re looking at what the year meant for classical music…through the premieres that defined it and the larger artistic movements they all illuminated.

Puccini’s Farewell and the End of Italian Grand Opera

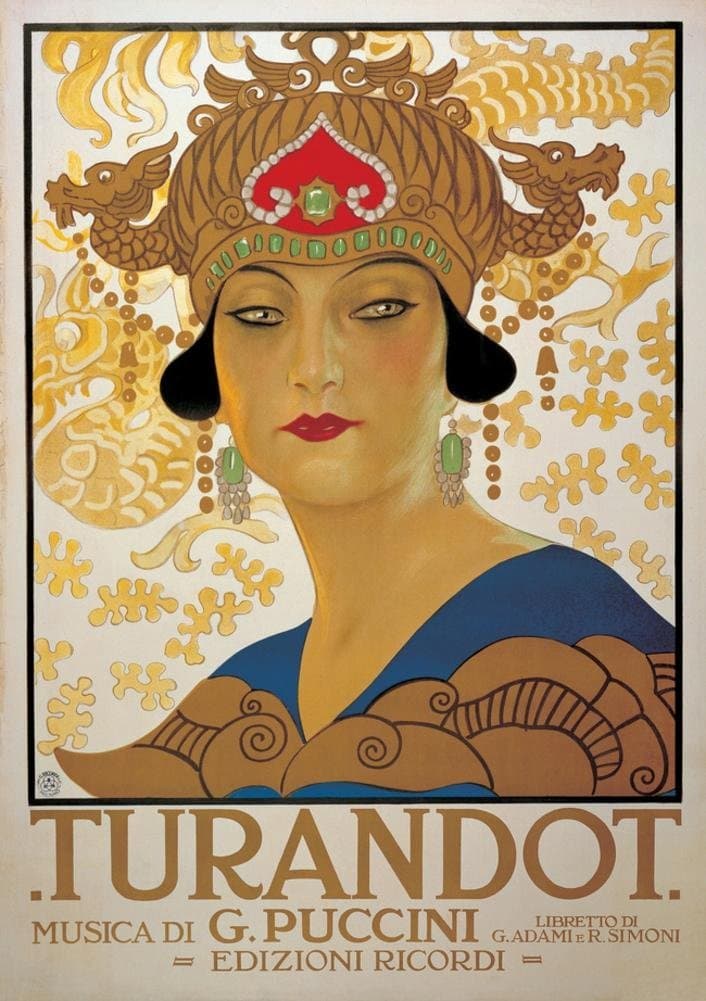

Puccini: Turandot

When Giacomo Puccini died in 1924, he left Turandot unfinished.

Composer Franco Alfano completed the score, and the work had its long-awaited premiere at La Scala on 25 April 1926, a night that instantly entered operatic lore.

Poster of Puccini’s Turandot

During Act III, conductor Arturo Toscanini laid down his baton to announce to the audience: “Here the performance finished because at this point the maestro died.”

The following night, the opera was performed in full with Alfano’s completion.

Lavish, opulent, and harmonically rich, Turandot has come to symbolise the end of Italian grand opera: Puccini simply had no heirs that could match his influence.

It was a final, blazing flourish for a genre that had shaped European musical life for generations…and a hint of what the rest of the year would bring.

Modernist Opera Pushes the Boundaries

In many ways, Turandot looked backwards. But a handful of new operas were pushing the genre in a very different direction.

Three premieres from 1926 alone showed how radically the genre was transforming:

Kurt Weill’s Der Protagonist, a one-act study in expressionism and psychological tension, premiered in March.

In November, Paul Hindemith’s Cardillac premiered: a brutal, meticulously crafted thriller.

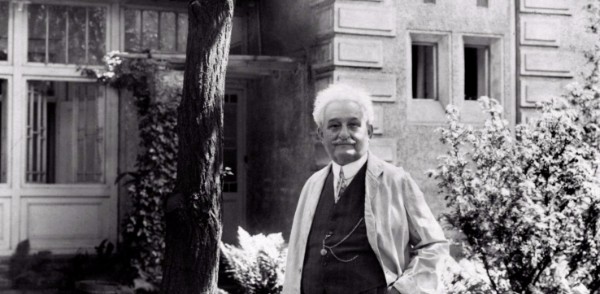

Leoš Janáček

The following month, in December, Leoš Janáček’s The Makropulos Case offered a meditation on immortality, made unique by Janáček’s technique of employing distinctive speech-derived motifs.

Remarkably, Janáček was four years older than Puccini, but in his later years, he’d been able to find a modern musical language that the Italian hadn’t.

Taken together, these works signaled opera’s break from Romantic grandiosity (some might call it “excess”). Opera in 1926 was becoming leaner, sharper, more psychologically charged.

Janáček’s The Makropulos Case

Modernism in the Concert Hall

This same shift was happening in instrumental music, too.

By 1926, the radical ideas of the Second Viennese School were steadily gaining ground.

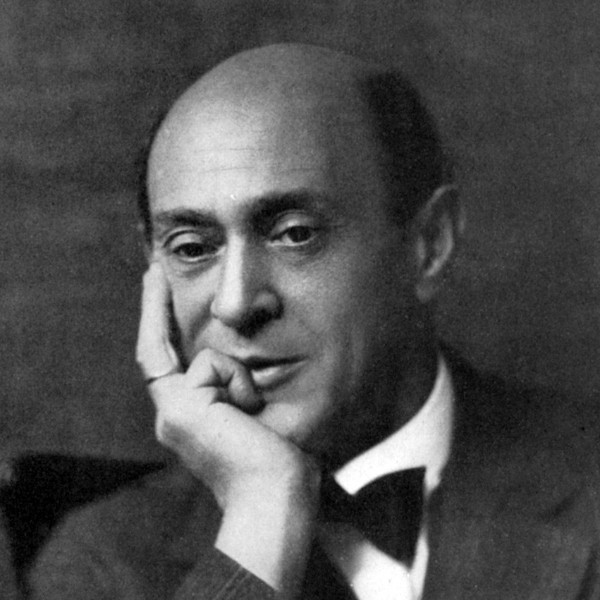

Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg, its founder, was teaching his twelve-tone method; Alban Berg began his Lyric Suite; Anton Webern pursued ever more condensed, ever more crystalline forms.

The existence of atonality was no longer a scandal. It was becoming a recognised avant-garde vocabulary – whether general audiences liked it or not.

Berg’s Lyric Suite

Historic Forms Return to the Spotlight

In an intriguing countercurrent, 1926 also saw a blossoming fascination with the music of the past.

On 4 November, harpsichordist Wanda Landowska premiered Manuel de Falla’s Harpsichord Concerto in Barcelona.

Wanda Landowska

Its crisp textures and Baroque-inspired clarity helped reignite interest in early instruments and performance practice.

Manuel de Falla: Concerto per Clavicembalo | Esfahani & OSCyL · MarchVivo

And Landowska was far from alone. Composers across Europe, following trails blazed by Stravinsky and Respighi in the years immediately prior, began mining earlier musical styles for inspiration.

Composers began coming out with works that boasted Baroque forms, modal language from the Renaissance, and a preoccupation with neoclassical transparency and order.

The result was a musical landscape where radical modernism and historical revival existed side by side.

America Starts Finding Its Voice

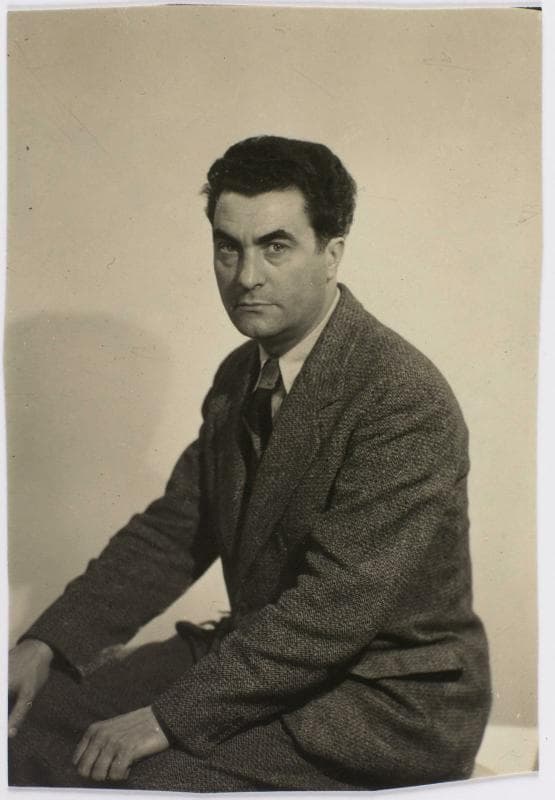

Man Ray: Edgar Varèse, ca. 1930 (Paris: Centre Pompidou)

The United States, newly ascendant culturally and economically after the First World War, was beginning to shape a distinct musical identity.

On 9 April, the Philadelphia Orchestra under Leopold Stokowski premiered Edgard Varèse’s Amériques: a roaring, industrial portrait of urban life complete with sirens and massive percussion.

It captured a new kind of modernism: noisy, mechanical, and unmistakably American.

Varèse’s Amériques

At the same time, Aaron Copland and George Gershwin were exploring how jazz might inform “serious” concert music.

Copland’s Piano Concerto fused jazz language with angular orchestration (he had just returned from study in Paris).

Copland Plays Copland Piano Concerto

Meanwhile, Gershwin’s Three Preludes brought blues harmonies to the concert stage.

Krystian Zimerman plays Three Preludes by George Gershwin

All of these works were written in 1926.

Jazz was no longer a novelty: it was becoming increasingly central to contemporary composers’ musical languages.

Jazz Crosses the Atlantic

European composers were absorbing these sounds with equal enthusiasm.

Ernst Krenek’s Zeitoper Jonny spielt auf (drafted in 1926) would electrify European audiences the following year.

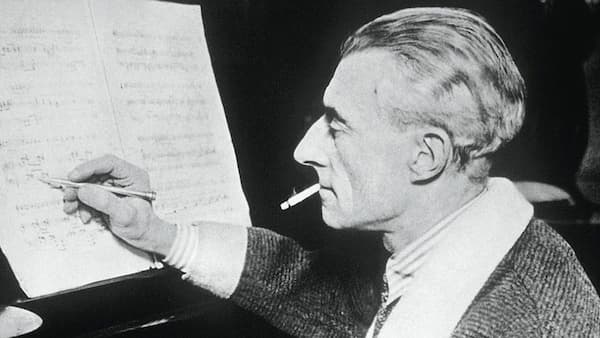

Maurice Ravel in 1928 © Fototeca Gilardi / akg-images

Maurice Ravel was increasingly fascinated by blues; his interest in American music would come to full fruition two years later, during his four-month tour of the country in 1928.

Darius Milhaud had been captivated by jazz since his 1920 visit to Harlem.

By 1926, jazz was a global force reshaping the language of classical music.

National Identity

Dmitri Shostakovich, 1940

On 12 May 1926, nineteen-year-old Dmitri Shostakovich premiered his Symphony No. 1 in St. Petersburg.

It was an immediate triumph, and it marked the arrival of a major new voice in the Soviet Union: one who would carry Russian symphonism into the modern century.

Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 1

Then, a month later on 26 June, the premiere of Janáček’s Sinfonietta in Prague, with its blazing brass fanfares and folk-rooted rhythms, became a national cultural event, demonstrating how folk traditions could transform into dazzling orchestral showpieces.

Janáček’s Sinfonietta

Romanticism’s Final Breath: Sibelius’s Last Major Work

Jean Sibelius, 1923

The final major premiere of the year was one of the most bittersweet.

On 26 December, New York audiences heard the premiere of Jean Sibelius’s Tapiola: a dark, atmospheric tone poem inspired by Finnish forests and myth.

Although Sibelius would live for nearly three more decades, this was his last major composition.

Just as Turandot had, in the spring, marked the final gasp of grand Romantic opera, Tapiola could be interpreted as the last gasp of Romantic orchestral music.

Sibelius’s Tapiola

Although several other composers would go on to write operas and orchestral music in the late Romantic style (Richard Strauss, for instance, continued composing in said style until his death in 1949 at the age of 85), after 1926, their music would feel increasingly anachronistic.

Music had moved on, and decisively.

Conclusion: A Year When Musical Styles Coexisted and Set the Stage

With a century’s hindsight, 1926 stands out not because one style prevailed, but because so many did.

It was a year when:

- Puccini and Sibelius offered audiences their final masterpieces.

- Varèse’s and the Second Viennese School’s carefully calibrated noise, and Weill and Hindemith’s tautly constructed works, were heralding the future.

- Shostakovich’s symphonies, Janáček’s fanfares, and Copland and Gershwin’s works became points of national pride.

- Jazz cemented its importance and relevance to concert composers internationally.

- Composers and performers became increasingly inspired by long-past music history.

- Modernism, jazz, nationalism, and neoclassicism overlapped and intertwined.

In short, classical music in 1926 was setting the stage for the next century of concert music. And in doing so, it produced works that still challenge and inspire us a hundred years later.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Some of the greatest music ever composed was initially despised or not appreciated. Sometimes, it takes years, decades even, before a piece is recognized . Is this the fault of the critic? The audience? Or both? Is it just down to personal taste/opinion, or just that a particular piece does not do what the critic or audience expects it to do? Obviously, some pieces are ahead of their time, and need contemporary listeners to catch up with them, which may indeed take some time to be acknowledged. Anything really outstanding will eventually be more understood and appreciated. It’s the old cliche of ” the test of time”- great music will be timeless, and live on through the centuries, just like the best art and literature…….