If you’ve ever listened to a piece by Chopin, Liszt, or Bartók and wondered what those strange numbers attached to their works – like WoO 18, L. 123, or Sz. 95 – mean, you’re not alone.

These catalogue numbers are useful tools for performers, scholars, and audiences alike. But they can be confusing to decode, especially since different composers are classified under different systems.

Today, we’re demystifying the cataloguing systems of Romantic and early modern composers and exploring what those cryptic letters and numbers really mean.

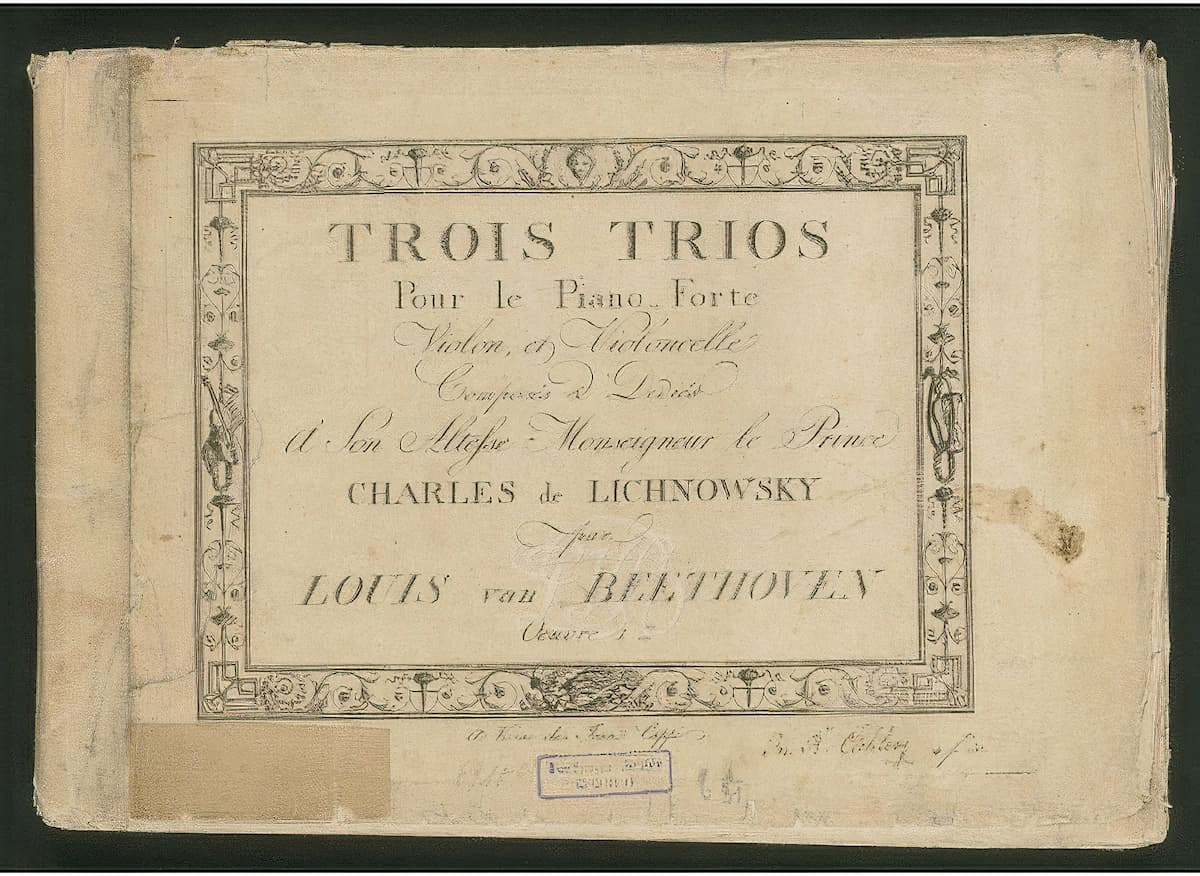

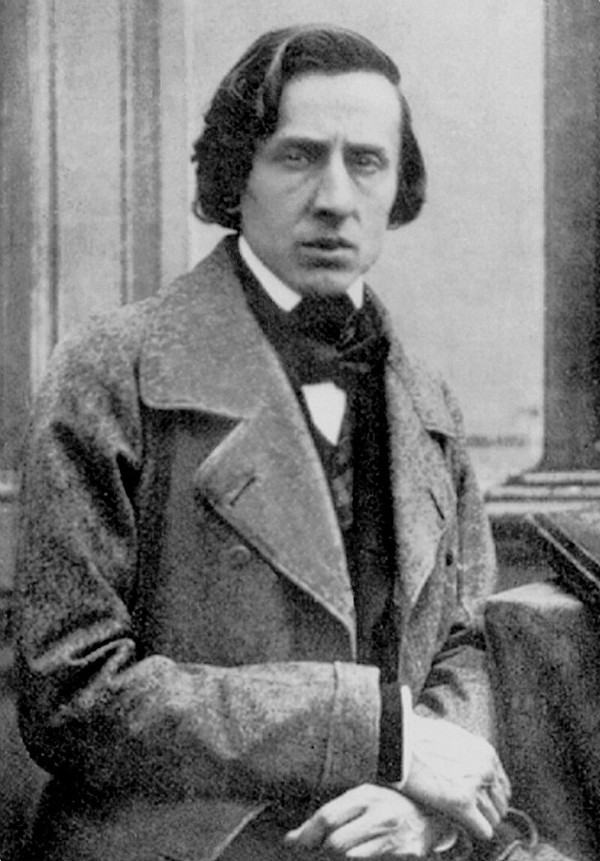

Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849)

B numbers

Chopin’s Waltz in A Minor, B.150

B numbers originated with British musicologist Maurice J. E. Brown (1906–1975). He studied physics at university and became the science head at Marlborough Grammar School in Wiltshire, England.

In his spare time, Brown studied music and wrote books about composers. His first love was Franz Schubert. In 1958, he published Schubert: A Critical Biography, which became one of the most important Schubert biographies of the twentieth century.

Frédéric Chopin

Another one of his projects was numbering all of Chopin’s unpublished works. He produced that catalogue in 1960, two years after his Schubert biography.

There are also other experts who assembled lists or catalogues of Chopin’s works, including Krystyna Kobylańska and the contributors to the Chopin National Edition. However, B numbers are most common.

Richard Wagner – WWV (1813–1883)

WWV numbers

Wagner’s Albumblatt, WWV 94

In 1950, musicologist Wolfgang Schmieder released a project called the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis (Bach Works Catalogue), which gave a number to all thousand-plus works by Bach. This created a model for future composer catalogues.

Three musicologists (John Deathridge, Martin Geck, and Egon Voss) joined forces in the 1980s to create a similar catalogue for the works of Richard Wagner.

It was dubbed the Wagner-Werk-Verzeichnis (Catalogue of Wagner’s Works) and consisted of all 113 of his works for the stage and the concert hall. This is where the abbreviation WWV comes from.

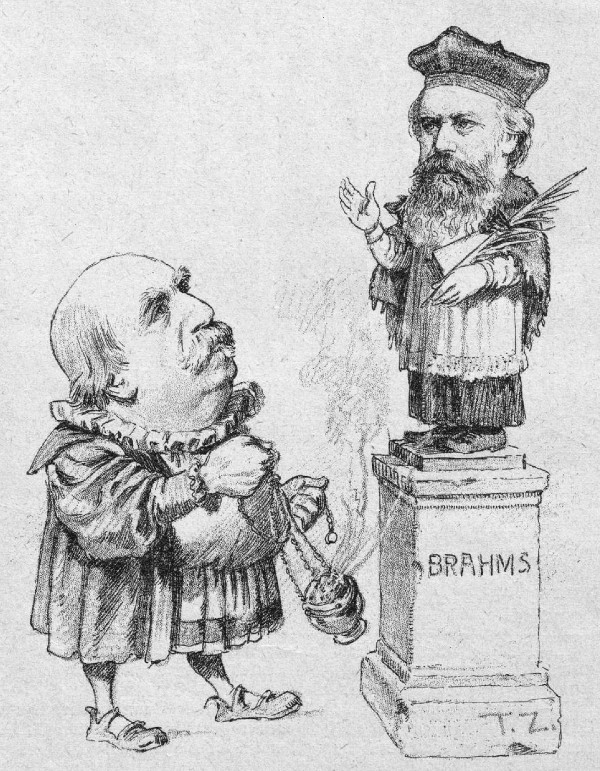

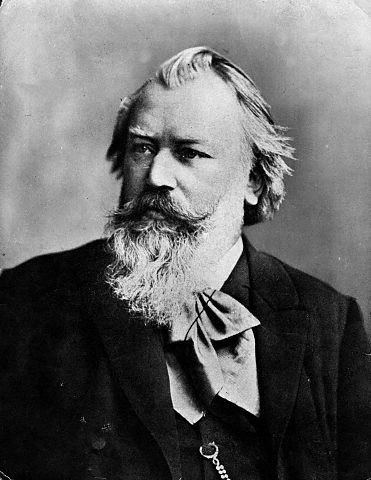

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

WoO numbers

Brahms’s Hungarian Dance No. 1, WoO 1

Many of Brahms’s works were published, which means that they have opus numbers. However, some unpublished works still exist.

Like other composers with unpublished works, these Brahms works have been given a WoO by musicologists. “WoO” stands for “Werke ohne Opuszahl” (Works Without Opus Number).

Johannes Brahms

The musicologist who spearheaded this effort for the works of Brahms was Margit L. McCorkle. She’s the only musicologist on this list who catalogued two major composers’ works: Brahms’s and his mentor Robert Schumann’s.

McCorkle was born in 1942, was a concert pianist and harpsichordist, and studied Brahms alongside her husband, Donald M. McCorkle, who was Head of Music at the University of British Columbia.

After his death in 1978, she worked on cataloguing Brahms’s work, publishing it in 1984. That year, she earned the Order of Merit from West Germany for her work.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893)

TH numbers

Tchaikovsky’s Six Romances, Op.6, TH 93

Russian-American Tchaikovsky scholar Alexander Poznansky has written a number of biographical works on the composer, including the psychological biography Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man and Tchaikovsky’s Last Days. Today he works as a librarian at Yale.

Poznansky and Brett Langston assigned TH numbers to all of Tchaikovsky’s works in their 2002 book The Tchaikovsky Handbook, Vol.1.

The TH numbers are different from the opus numbers; TH numbers also track arrangements, unfinished works, etc.

Richard Strauss (1864–1949)

TrV numbers

Strauss’s Oboe Concerto in D Major, TrV 292

Richard Strauss published 88 compositions; the rest weren’t assigned opus numbers, so were ripe for later historians to catalogue.

The first incomplete catalogue of Strauss’s works was assembled by German musicologist Erich Hermann Mueller von Asow (1892-1964). He published the catalogue in 1959, just a decade after Strauss’s death.

New scholarship came to light after von Asow’s death. That led to musicologists Franz Trenner and Alfons Ott creating an updated version of the Strauss catalogue.

In 1985, Franz Trenner returned to the project and came out with a new chronological catalogue. His son Florian Trenner finished the project and published it in 1999. Numbers from this catalogue are known as “TrV” numbers (short for Trenner Verzeichnis).

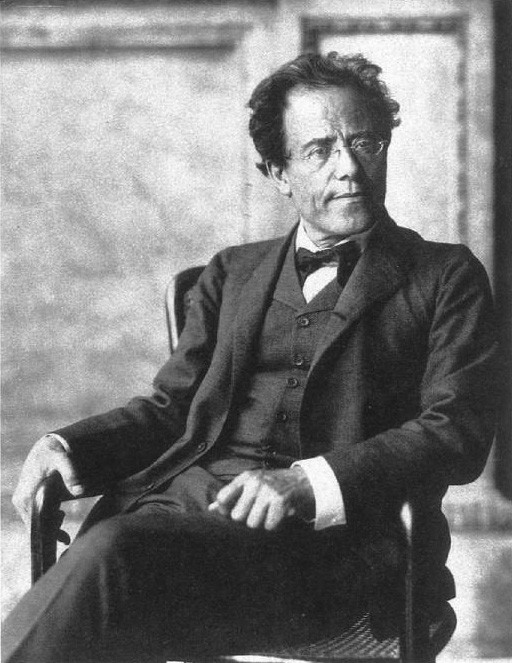

Gustav Mahler (1860–1911)

GMW numbers

Mahler’s Symphony No. 4 in G Major, GMW 37

This is the most recent catalogue on the list: it was created in 2021-22 by the Internationale Gustav Mahler Gesellschaft (International Gustav Mahler Society). It is sorted chronologically by composition date, not by work type.

Gustav Mahler

According to their website, here’s how they decided to sort different kinds of works:

Different versions of a work are combined into groups of works, such as the three- and two-movement versions of Das klagende Lied (GMW 1; 1,1) or the three versions of the First Symphony (GMW 11; 11,1; 11,2).

Parts or movements of multi-part works, as well as individual songs from song cycles, are denoted with lowercase letters (GMW 1a).

Songs that exist in both piano and orchestral versions are distinguished by the capital letters K and O (GMW 21-K; GMW 21-O).

Leoš Janáček (1854–1928)

JW numbers

Janáček’s Idyll for string orchestra, JW 6/3

The catalogue of Janáček’s works was published in 1997 by musicologists Nigel Simeone, John Tyrrell, and Alena Němcová.

In the JW catalogue, the first number indicates the genre; there is always a slash in the middle; and the second number indicates the specific work.

For example, Janáček’s opera The Cunning Little Vixen has the JW number 1/9: the one indicates it’s an opera, and the nine indicates which specific opera it is.

Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)

M numbers

Ravel’s Piano Trio, M. 67

Marcel Marnat (1933–2024) was a French musicologist and writer who was self-taught. He became an expert in Maurice Ravel and was the secretary of the Ravel Foundation for a while.

He created a catalogue of Ravel’s works, arranging them chronologically by date of completion.

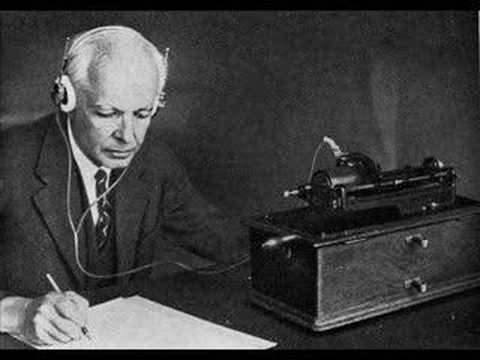

Béla Bartók (1881–1945)

Sz., BB, and DD numbers

Bartók’s Divertimento for String Orchestra, Sz.113, BB.118

The way that Bartók handled cataloguing his works is fascinating…and complex.

Because of his interest in preserving and arranging folk music, Bartók himself wasn’t sure which works to list as his own. Over the course of his life, he renumbered his opus numbers three times!

Béla Bartók notating folk music

Hungarian composer András Szőllősy (1921–2007) studied with Béla Bartók’s colleague Zoltán Kodály at the Franz Liszt Academy of Music in Budapest.

In 1972, Szőllősy published what’s known as the Szőllősy index of Bartók’s work. That’s why you’ll sometimes see Bartók’s work listed with a number that starts with Sz.

Although the Szőllősy index remains the most popular, others also created their own catalogues. BB numbers were created by Hungarian musicologist László Somfai, while chronological DD numbers were created by Denijs Dille, a Flemish priest and friend of Bartók.

Claude Debussy (1862–1918)

L numbers

Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, L. 86

François Lesure (1923–2001) was a French musicologist best known for his study of Debussy. He became the head of the music department of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in 1970.

In 1977, he published his first catalogue of Debussy’s work. That is listed as a piece’s L¹ number.

In 2003, two years after his death, his revised catalogue became available, and created an updated L² number for each work, too.

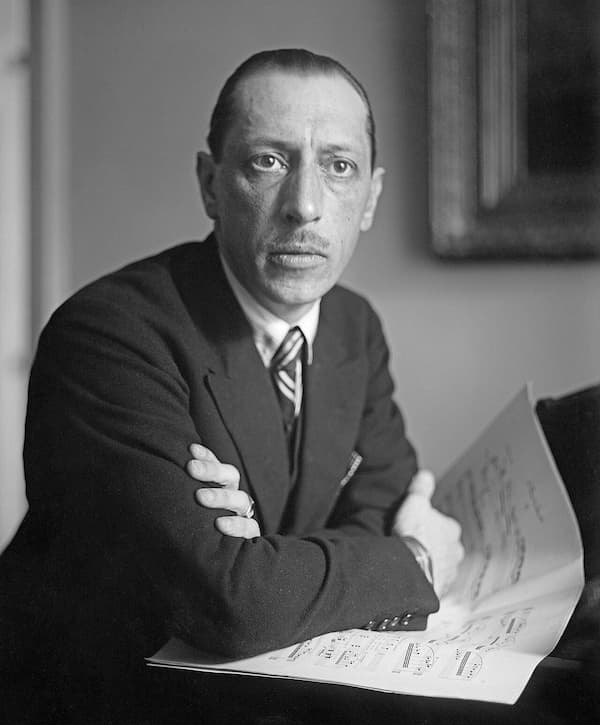

Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971)

K numbers

Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, K052

German musicologist Helmut Kirchmeyer (1930–) assembled the catalogue of Igor Stravinsky’s works. He was born in Düsseldorf, studied at the University of Cologne, and gave his senior thesis on Stravinsky.

Kirchmeyer’s interests extended far beyond music; he studied legal history, criminology, and sociology, too.

In 2002, he published a catalogue of the complete works of Stravinsky.

Photo of Igor Stravinsky. Taken by George Grantham Bain’s news picture agency.

Unique among the catalogues we’ve discussed, the “K catalogue” (as the Kirchmeyer catalogue is known) has its own website: https://www.kcatalog.org/.

Here’s its description of the information you can find there:

In addition to its directory of works, the K Catalog contains notes related to performances including information about roles and playing times, editions with their sales results, short analyses, information on biographical assignments, and historical performances.

Here, anyone can see the full catalogue, submit questions, and learn more about the project. It’s a fascinating stop for anyone who loves Stravinsky’s music.

The K catalogue continues to be updated even today.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter