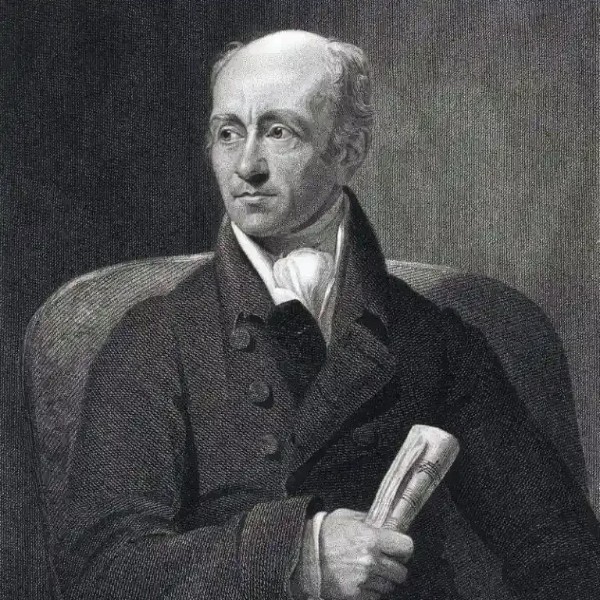

Muzio Clementi (1752–1832) may not always get the recognition of Mozart or Beethoven, but to pianists, his stature is beyond dispute.

Often called the “Father of the Pianoforte,” Clementi transformed the early keyboard sonata from a simple dance or exercise into a vehicle for virtuosity and expression. He combined technical brilliance with lyrical elegance, setting a new standard.

Muzio Clementi

Clementi did not merely write for the piano; he actually invented its modern voice. While his output is vast, certain sonatas stand out as favourites among performers and audiences alike. To celebrate his birthday on 23 January, let’s explore ten of Clementi’s most popular and beloved piano sonatas.

Muzio Clementi: Sonata in B-flat Major, Op. 24, No. 2

When Mozart borrowed from Clementi

Let’s get started with one of Clementi’s most famous sonatas, one that includes a telling anecdote. In 1781, in Vienna, Emperor Joseph II staged a famous keyboard duel between the young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and the Italian virtuoso Muzio Clementi, then Europe’s most celebrated piano star.

Clementi performed, among other things, the opening of his Piano Sonata in B-flat major, Op. 24 No. 2, whose first movement begins with a distinctive rapidly repeated-note figure in the right hand.

Mozart praised Clementi’s brilliance but wrote to his father, “Clementi has no taste or feeling… he is a mere mechanicus.” Fast-forward a few years, and when Mozart composed the overture to The Magic Flute in 1791, listeners noticed something striking.

The overture’s main “Allegro” theme features the same repeated-note figure, unmistakably reminiscent of Clementi’s sonata. Clementi also noticed, and in later editions of his sonata, he quietly pointed out that he had used the idea first.

Muzio Clementi: 3 Piano Sonatas, Op. 50: No. 1 in A Major (Tanya Bannister, piano)

Inventing the Piano’s Personality

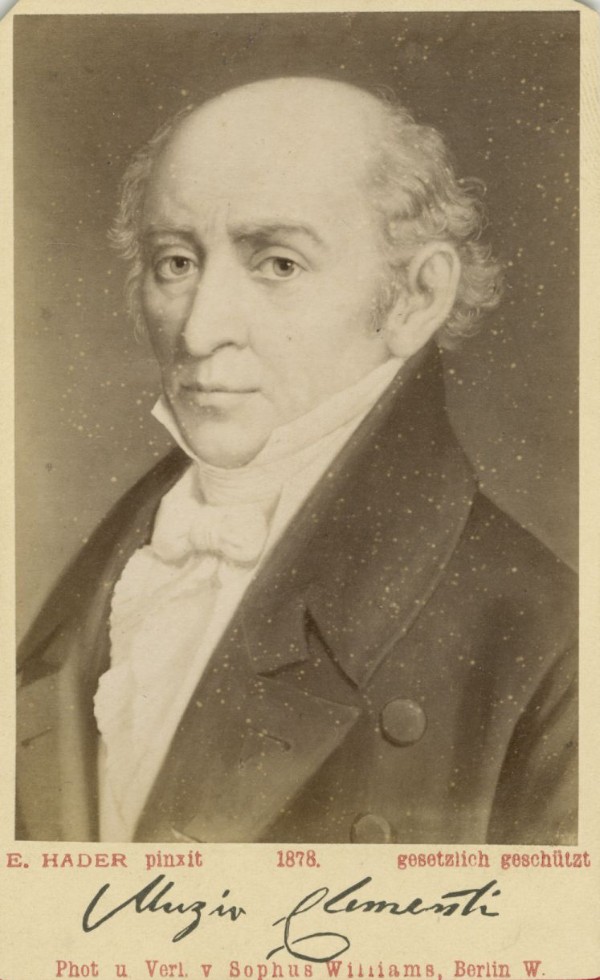

Muzio Clementi

Muzio Clementi understood the piano as a new kind of instrument at a time when it was still finding its place. In the late eighteenth century, the harpsichord was still dominant, and many composers treated the piano as a louder substitute rather than something truly different.

Clementi heard otherwise. He recognised early on that the piano could shape sound, colour phrases, and respond to touch in ways no earlier keyboard could.

Clementi wrote with the physical feel of the piano in mind. Just listen to the sunny and charming sonata from Clementi’s final set.

The flowing melodies, playful dialogue between hands, and rhythmic bounce make this sonata immediately appealing. Its graceful finale, full of trills and sparkling figurations, leaves the listener smiling.

Muzio Clementi: Sonata in G minor, Op. 7, No. 3

Where Technique Meets Charm

Clementi’s sonatas explore how fingers move across the keys, how weight and balance affect sound, and how clarity can be maintained even at high speed. The fast passages are not just there to impress.

These fast passages train control, evenness, and precision. In this way, Clementi helped define what modern piano technique would become.

Clementi’s sonatas have a cheerful and charming way of expressing emotion. They show feeling through the way the music moves, as sudden changes in volume can surprise you. A gentle turn of phrase may convey warmth, a buoyant rhythm radiating good humour.

Just listen to the darker and more dramatic Op. 7, No. 3. This sonata already hints at the stormy moods later explored by Beethoven. The opening “Allegro agitato” immediately immerses the listener in tension, with the “Largo” providing a tender respite.

Muzio Clementi: Piano Sonata in G Major, Op. 40, No. 1 (Pietro De Maria, piano)

From Whisper to Sparkle

Muzio Clementi

Dynamics play a central role in Clementi’s music. Crescendos and diminuendos are not decorative extras but part of the musical story. Clementi uses gradual changes in volume to build tension, shape phrases, and guide the listener through a movement.

This was a major step away from the sudden loud–soft contrasts of harpsichord music and a clear sign that he was thinking specifically in pianistic terms.

Just as important is Clementi’s belief that the piano could sing. Many of his slow movements unfold like vocal arias, with long, flowing melodies supported by gentle accompaniments.

Op. 40, No. 1 is sometimes dubbed “The Brilliant.” Living up to its nickname, virtuosic runs, crisp staccatos and sparkling scales dominate the “Allegro.” But it’s not all flash, as each flourish serves the overall structure and character of the piece.

Muzio Clementi: Sonata in F-sharp minor, Op. 26, No. 2

Building the Modern Piano

So far we have met Muzio Clementi the great composer and pianist. However, he was also very important in the world of pianos themselves. He understood the piano not just as an instrument to play, but as something that could be improved, built, and shared with others.

In the late 1700s, pianos were still fairly new, but by Clementi’s maturity, the piano was gaining ground, especially in England. Most people were used to the harpsichord, and early pianos could be small, quiet, or uneven in sound. Clementi noticed this and realised that the piano could do much more than just be a louder harpsichord.

He wanted pianos that could respond better to a player’s touch, make smooth sounds, and carry music beautifully in big rooms.

And the result is heard in Op. 26, No. 2, one of his most dramatic and introspective sonatas. The dark key gives the music a stormy quality, with the middle movements offer moments of calm. And there is restless energy in the final movement.

Muzio Clementi: Sonata in C Major, Op. 34, No. 1

From Workshop to Keyboard

A piano manufactured by Muzio Clementi & Co

Clementi didn’t just play pianos, he also got involved in making and selling them. He worked closely with Broadwood and other piano makers in London, giving advice on how the instruments could be improved.

He knew exactly what a pianist needed. Keys that felt right under the fingers, allowing for both fast passagework and delicate phrasing. Pedals had to work smoothly, and strings needed to produce clear and bright tones that carried in larger rooms.

Because of this careful attention to these details, the pianos he helped design were not only more reliable than many others of the time but also far more expressive. Pianists could shape their music with greater nuance, play more demanding pieces, and explore the instrument’s full emotional range.

Clementi’s Op. 34 No. 1 is bright, cheerful, and full of energy. The music moves quickly, with lively rhythms and playful melodies that make it feel light and joyful. Actually, the hands often create fun little musical conversations. It attracted attention from pianists like Horowitz and Gilels.

Muzio Clementi: Piano Sonata in G minor, Op. 50, No. 3

Selling Sound and Influence

Clementi also became a piano dealer. He sold pianos across England and Europe, helping to make the instrument popular. A good many students, teachers, and professional musicians bought pianos from him, spreading the instrument.

His work as a dealer was important because it gave people access to high-quality pianos and helped the instrument grow in popularity. This improved performance standards, and it helped the piano become more popular and more widely used.

Through his work as a builder and dealer, Clementi influenced both the sound of the piano and the way it was played. His ideas helped shape modern piano design, and his business helped the piano become a household instrument across Europe.

Clementi’s Op. 50 No. 3 is full of energy, optimism, and elegance. After a more dramatic introduction, the sonata shows its playful side. It balances virtuosic flair with graceful melodies, making it a favourite for both performers and audiences.

Muzio Clementi: Piano Sonata in F Minor, Op. 13, No. 6 (Luca Rasca, piano)

A Virtuoso Blueprint

Muzio Clementi

Clementi’s piano sonatas reveal a careful balance of virtuosity and musical expression. Fast scales, arpeggios, and leaps were never merely technical showpieces but were integrated into musical phrases that demanded clarity, precision, and lyricism.

It was this combination that caught Beethoven’s attention. Beethoven owned and studied Clementi’s sonatas closely, copying passages for his own learning. Scholars note that Beethoven absorbed Clementi’s approach to writing for the piano.

This is particularly evident in the clear distinction of voices, the use of dynamic contrasts, the slow introductions, and the balance of technical challenge with expressive depth.

Some of the driving energy and virtuosic passages in Beethoven’s early sonatas owe a clear debt to Clementi’s style. Clementi’s approach provided the blueprint for balancing virtuosity with expression, giving Beethoven the foundation on which to build his distinctive voice.

Muzio Clementi: Sonata in B minor, Op. 40, No. 2

Clementi’s Lasting Influence

But Beethoven was not Clementi’s only admirer. Johann Nepomuk Hummel, a virtuoso and pupil of Mozart, also drew inspiration from Clementi. Hummel’s piano works often echo Clementi’s clarity of phrasing and meticulous attention to finger technique.

Clementi’s influence extended beyond composition. His teaching methods and published exercises, most notably the Gradus ad Parnassum, trained generations of pianists in precision, control, and musicality.

In the end, Clementi was more than just a composer and performer. He was a thinker, a designer, and a businessman who cared about the piano in every way possible. He thought deeply about how the instrument should feel and sound at home and in the concert hall.

His legacy is not only in the music he wrote but also in the instruments that made the music possible, and he taught pianists how to bring that music to life. Clementi’s impact can be felt not just in notes on the page, but in the very way the piano is played and understood today.

Muzio Clementi composed at least 60-70 piano sonatas, up to 110 if you include variants, duplicates, and arrangements, during his lifetime. So, my top 10 are just the tip of the iceberg. What are your favourites?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter